“Gardening is healthy, it’s interesting, and it promotes diversity. It gets you out of the box watching television and being an audience; always being catered to, pandered to, and ripped off while your resources are squandered. As a gardener, you can fulfill a destiny: The divine is closer to you in the garden than anywhere else. That’s not true if you spray poisons and you kill every bug and you discriminate, but if you have a touch, and you get into the flow of the beauty of nature, you have a chance to feel the illumination that comes with love and peace and goodness.” —Alan Kapuler(1)

“The most important components, beyond climate, of any self- sufficiency gardening program are the soil or ground in which you will grow your garden and the plant and animal populations that you encourage to or discourage from living there. To be effectively self-reliant, whether by choice or necessity, your goal should be a healthy, well-balanced garden environment which is self-sustaining, that is, does not require the purchase of commercial soil amendments, pesticides, herbicides or beneficial insects. That may seem an impossible goal in a culture programmed to buy solutions to all of our problems, but it is not impossible if you will work intimately with Nature, using what is commonly known as organic gardening techniques, to build a healthy, non-toxic garden environment. [Thus,] building a self-sustaining garden environment that can support the goal of food self-sufficiency may require some adjustments in thinking.”

—Geri Welzel Guidetti(2)

Full of Life

The word human comes from the same roots as the word humus, meaning “earth,” and in fact our bodies do contain many of the same elements and microorganisms as fertile organic soil. To build a garden that will effectively nurture us, we need first and foremost to nurture a healthy soil community.

For many years soil studies focused primarily on minerals and rocks, but now scientists understand that the soil is a life force that is constantly moving and renewing the ground beneath our feet. In his revolutionary book The Soil and Health, Sir Albert Howard wrote, “The soil is, as a matter of fact, full of life organisms. It is essential to con- ceive of it as something pulsating with life. . . . There could be no greater misconception than to regard the earth as dead: a handful of soil is teeming with life.”(3)

Whole communities thrive within every gram of topsoil, including arthropods, fungi, algae, roots, nematodes, protozoans, worms, springtails, and a billion different kinds of bacteria. As they move through the soil, eating, breeding, interacting, dying, and decomposing, they create a complex web of life that makes it possible to have clean air, clean water, healthy plants, and moderated water flow.

Some microorganisms store or “fix” nitrogen and other nutrients, making them available to hungry plants. Others moderate soil structure by secreting substances that enhance aggregation and porosity; this increases water filtration and the holding capacity of soil and reduces erosion and wasteful runoff. Leaves and roots can produce exudates, which provide food for bacteria and fungi. Protozoans move soil around, and nematodes eat disease causing organisms. These critters interact with the rest of the soil community, feed on one another, and in turn nourish the plants and bring them to fruition. The plant and soil communities support each other in constantly pulsating, ever evolving, living ecologies.

This is, of course, a simplified description of complex systems, and typically the more complex a soil community, the more ecologically sound it is. In general, perennial polycultures, such as those described in this book, will support a much more complex soil ecosystem than annual monocultures such as a potato farm or a cornfield.

Dr. Elaine Ingham, an accomplished soil scientist from Oregon, finds that a balanced, complex “soil food web” will suppress disease causing and pest organisms; make nutrients available for plant growth at the times and rates plants require; decompose plant residues rapidly; produce hormones that help plants grow; and retain nitrogen and other nutrients such as calcium, iron, potassium, phosphorus, and more. She emphasizes the importance of bacteria and fungi in particular, noting our own dependence on the six million bacteria on every square centimeter of our skin.(4)

Soil health is linked to our own health, and soil communities bear remarkable resemblance to the flora and fauna in our own guts, with many similar microorganisms. Just as we must maintain a diverse, thriving intestinal community to be healthy, we must also cultivate a diverse, thriving soil ecosystem.

Unless agronomy is your passion we needn’t dwell too long on the science. We need only understand that the soil is a living, dynamic system, affected by every action we take, for good or ill. Throughout history we find examples of societies that thrived and rose to power on fertile native soil, then waned and perished when they failed to adequately steward that soil.

When we build soil we build community in more ways than we know, and when we destroy soil we destroy our chances at a thriving global community. In short, engaging in responsible, proactive soil stewardship will help guarantee the abundance and long-term fertility of our gardens—and in turn our communities. In order to achieve this it is important to establish soil cycles that perpetuate their own fertility, and to grow our crops with the surplus nutrients created by such a system. This will become easier over time as the soil and the ensuing gardens expand and mature.

If you really want to geek out on soil science, check out the resources section for a list of excellent books and websites. In the meantime this chapter is packed with soil building strategies that will diversify your living soil community and help guarantee a long lasting, healthy, and abundant ecological garden.

Starting or Expanding Garden Beds

Generally, if an area will yield lush green grass, then it will yield a lush, diverse garden. There may be exceptions to this rule, but I have seen none. Every time I witnessed or helped with a lawn conversion the resulting garden was lush and abundant, and the owners were thrilled to let the lawn become a thing of the past. If you have a lawn space and are ready to turn it into a garden, I am here to tell you how fun and easy it really is.

Whether you choose to garden the whole yard or just a section of it, remember that good care of the soil is the key to your success. The next few pages will describe some excellent strategies for pioneering or expanding garden beds in ways that are good for the soil. They will work well on almost any site, so experiment with them all and see what works best in your particular situation. Use a variety of methods to increase the deep diversity and long term fertility of your soil, and it will reward you with a lifetime of health and abundance.

Before you start building and improving soil, however, you should assess the soil that is already there and try to determine which strategies would work the best.

Meet the Neighbors

The best way to improve soil is to diversify the living community within it. How to do so depends on what is already there and what the soil needs to achieve optimum balance and fertility. There are a number of good ways to help determine these needs, from simple pH kits to expensive laboratory soil analysis. These store bought solutions are effective in some settings, but unnecessary for most home gardeners.

Before you go out and spend money on soil test kits, go out into your garden and look at what’s already growing there. For centuries organic gardeners have relied on the plants themselves to indicate soil conditions, and many common weeds can provide excellent clues for how to improve your soil.

By learning to recognize weeds, we can learn about our specific soil conditions and begin adding specific types of organic matter that will help provide what the existing soil lacks. We can also plant relatives of the wild plants that will thrive in the same soil conditions, or we can replace unwanted weeds with our preferred cultivars.

Also, take some time to meet the varied critters who live in your topsoil. Depending on where you live, your topsoil is probably anywhere from half an inch to six feet deep. The topsoil is the most biologically active zone in the soil, and you improve it every time you mulch. Plant roots and biological activity also reach deeper, into the subsoil, where surplus moisture and nutrients are stored.

To get a nice view of your soil strata dig one or several small test pits, a foot wide by several feet deep. Use a flashlight to observe the varied levels of activity and changes in color. You will see an obvious switch from topsoil to subsoil. The topsoil will be dark and active and the subsoil will be lighter in color, heavier, and denser. Some sites have deep native topsoil while others have little or none, with bedrock lying just below the surface.

Take a handful of topsoil and squeeze it between your fingers. Does it clump together and stick to your fingers, or does it crumble and blow away?

The best soil is somewhere in between: spongy and light, with a diversity of textures, colors, and creatures. Look deep into the clods and try to see how the varied creatures interact. If you can’t find anyone living in your topsoil, then the strategies in this chapter will change that. If you already have good soil, teeming with life, then these methods will help you keep it that way.

Look back at the test pit and measure the depth of your topsoil with a ruler. Make note of your measurements and then fill in the pit or plant a tree there. Do this after each year of paradise gardening and you will see your topsoil getting progressively deeper, more diverse, and more full of life.

Bed Design

There are many things to consider when deciding what shape your garden beds will be, including contour, function, and efficient use of the available space. Millions of people grow gardens in boxes, but the rectangle is almost absent in nature—perhaps we should take heed and try something that makes more sense.

As we saw in the preceding chapter, the shape of your garden beds should adhere to the flow of water through your site. Build beds on contour and you will save water and prevent erosion.

But don’t limit yourself to long, curving rectangles either. While straighter beds are easier to maintain with machines, if you are working on a hand scale you should design your garden in patterns that make more ecological sense.

From a geometrical perspective, the best way to make use of a given space is with three way branching patterns. Nature uses branching patterns to distribute nutrients in plants and trees and to drain and distribute water across the land. Warm blooded animals also use branching patterns to transport blood and nutrients though complex vein and artery systems.In the garden, branching patterns use the least amount of path, minimizing travel time and maximizing bed space. Try a Y-pattern that uses 120-degree angles in sets of three—it sounds a little complicated, but you will end up with a visually spectacular and highly efficient garden layout.

Later, when you plant the beds, think again of branching and intersecting patterns, and space your plants accordingly. Straight rows are the least efficient use of space, so get creative and see how your space expands! By layering patterns into your design at each stage of the work, you enhance the fractal nature of your garden and thus its ability to thrive on multiple levels. Be sure to consider human flows as you shape your garden beds.

Pay attention to where people already walk through your site and shape the beds accordingly, rather than trying to get the people to conform to a new path.Be sure to consider human flows as you shape your garden beds. Pay attention to where people already walk through your site and shape the beds accordingly, rather than trying to get the people to conform to a new path.

Also, place beds in locations relative to what you want to grow. For example, build an herb spiral next to the kitchen door and you won’t have to run all the way out to the garden for a quick sprig of rosemary. Put another garden bed near where children play and grow flowers for them to pick.

Chapter 5 will give you even more ideas about bed design as we look at the many approaches to polycultural gardening, such as alley cropping and using hedgerows. For now let’s move on to soil building strategies.

Wisdom of the Weeds

By learning to recognize weeds (and what they tell) we can learn about our specific soil conditions and take action accordingly. We can also plant relatives of the wild plants that will thrive in the same soil conditions, or replace unwanted weeds with our preferred cultivars. Here is a quick-reference guide to a few common weeds and what they indicate about your soil. (Most of these plants are also edible and/or medicinal.)

Yellow dock & horsetail.

Soil is acidic or increasing in acidity. Plant cover crops, improve drainage, add non-acidic organic matter like straw and lime (but not wood chips.)

Morning glory/bindweed, wild mustard & pennycress.

Formation of surface crust or hardpan. Plant deep-rooted cover crops such as ryegrass and daikon. Allow dandelions, burdock and other tap-rooted weeds to remain, as hey will help break up the compacted subsoil. Add thick mulch and consider tilling/digging less often.

Lamb’s quarters, buttercup, pigweed, teasel & thistle.

Too much tilling and cultivation. Gardens that need a break will put out a lot of spiky and aggressive weeds. If it feels like you are constantly battling thistles and losing, consider letting that section of your garden fallow for a year or two. Sheet mulch with cardboard, straw and wood chips, and plant a cover crop of fava beans, vetch or ryegrass. Or, if you have the space, replant the area to perennial herbs, berries and trees, and start up a new veggie patch in a spot that isn’t so overworked.

Sweet peas, clover & vetch.

Sandy or alkaline soil, needs nitrogen. These weeds are an excellent cover crop. Leave them alone and let nature do the work for you. When they start to bloom, cut them down and mulch over, then plant your veggies on top.

Wild lettuce, lemon balm, self-heal, cleavers, chickweed & plantain.

Soil pH is balanced and/or ever-so-slightly acidic, soil is well-drained and fertile. Congratulations! These are the green-light weeds in your garden. This spot is ready for a fresh crop of vegetables. But be careful not to overwork, over-till, over-fertilize or add too much acidic material. Consider a careful rotation of crops to give your soil a chance to recover and re-adjust to the varied things you grow, and above all, enjoy yourself!

Compost Here Now

You can build compost anywhere, from a bucket in the kitchen to all over the front yard. Rich compost is worth more than its weight in gold in terms of garden success, and some form of it is essential for building soil. Some people build it in a shady corner near the kitchen door, then transport the finished compost over to the garden areas as needed.

I prefer to build compost right on top of the garden, in large, steaming piles that break down quickly. I then spread these piles around and plant into the resulting beds. This saves me from schlepping the wheelbarrow back and forth, and the big pile on the ground kills off the grass so I don’t have to dig it out.

Here is my method:

Mow the grass and punch some holes in the ground with a digging fork. If there are big, knobby weeds like blackberries, grub them out and shake the soil off the roots onto the bed. If there are a lot of rhizomatous weeds, such as bindweed, ivy, or some grasses, this and other sheet composting and mulching methods may not work.

These weed roots will just snake back and forth under the mulch/compost pile and form an impenetrable mat that eventually competes with your garden plants. See chapter 5 for more on how to deal with these extreme situations.

If all you have is regular grass and non-running weeds, you’re good to go. Once you’ve aerated the soil and gotten the big weeds out, spread a layer of unwaxed cardboard on the area you want to turn into a garden.

This space can be as large as you’ve got the materials to cover, but an area that’s about four feet wide and six to eight feet long is a good size for starters. I don’t recommend going any smaller than three feet by five—the pile won’t break down well enough or be easy to contain in such a small space. Try another technique for the little spots.

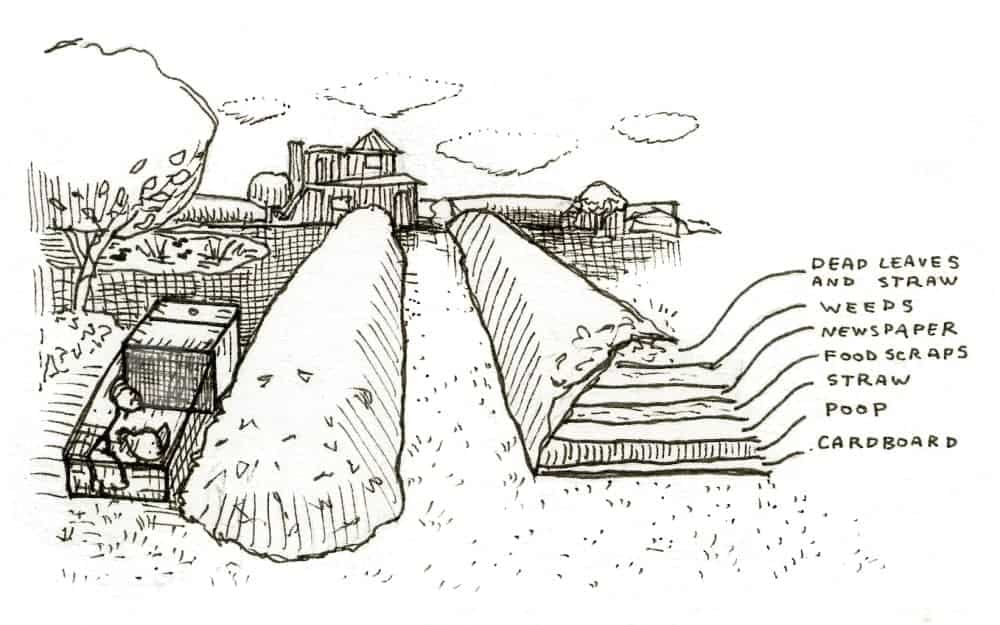

Soak the cardboard well with water and build your pile on top of it, alternating brown and green layers. The recommended ratio is twenty- five parts brown or carbonaceous material to one part green or nitrogen- rich material. “Brown” items might include straw, wood chips, cardboard, dried leaves, vacuum dust, fabric, paper, dryer lint, or small branches.

“Green” stuff might be fresh pulled weeds, feathers, food scraps, seaweed, fresh leaves, hay, or any kind of manure. Don’t use plastic, paint, or anything with nasty chemicals; take those to a toxic waste disposal site. Glass can be reused as a building material, but it doesn’t make good compost for obvious reasons.

Build up the pile as high as you can get it while still maintaining a sturdy form. Be sure to water each layer well before adding the next. If it gets too conical on top, dig a pitchfork into the center and pull material out to the edges so the pile is the same height all over—usually about five to six feet when freshly built.

Cover the pile with a protective shell of leaves, straw, or regular garden soil to keep the right critters in and the wrong critters (like rats) out, and aerate it periodically by stabbing the butt end of your pitchfork into the pile a few times. It is important that compost stay moist— though not dripping wet—so water it occasionally if needed or cover it with a tarp if it’s raining too much.

The Breakfast–Lunch–Dinner Theory

While you are building garden beds you may also want to start a few seeds. When growing plants from seeds, whether annual veggies or perennials, I subscribe to the Breakfast–Lunch–Dinner Theory.

It goes like this: Start seeds in their “breakfast,” meaning in a neutral medium with plenty of aeration but not too much fertility. I like to use a mixture of perlite, vermiculite, and/or pumice, with a little bit of sifted compost or topsoil.

When it comes to making potting soil it is hard to avoid buying the structural ingredients such as perlite, vermiculite, or pumice. Still, a big bag will last several years if you use it sparingly. Try to find local sources, preferably from your own site, and recycle old potting soil by spreading it out in the sun for a few days and mixing it back in.

When the seedlings have a few pairs of true leaves, transplant them into a slightly richer potting soil, or “lunch.” You can make a new mix similar to the above, but with more compost and less of the fillers, or just use the same mix and stir in a tiny bit of 3–1–1 fertilizer. Some gardeners use jauche (nettle tea), compost tea, and biodynamic preparations in their potting soil—try them all and see what you like. Again, be sure not to put too much fertilizer in the lunch mix, because it can burn the baby plants. Never add fresh manure to any potting soil—always compost the manure first, or save it for sheet mulching.

Finally, the garden beds in which the starts make their permanent home should provide a rich, fertile “dinner.” The Breakfast–Lunch–Dinner Theory doesn’t actually lend itself to human nutrition— eating our richest meal at the end of the day is a recipe for indigestion and obesity! Still, this system works well for starting and establishing new plants in the garden, so remember it when you need it.

Some people turn their pile every few days, while others prefer to let it take its own sweet time. To get the most out of your pile, use the biodynamic compost preparations described later in this chapter. A compost pile like this will take three to six months to break down. You can tell when it’s ready by the fresh, woodsy smell and dark, spongy texture.

Now you can use the finished product to top-dress any neighboring beds, and when the pile is low enough to suit your design, spread it around and plant it up. Don’t forget to set aside a little of the best compost for your potting soil, sifting it first—use a piece of hardware cloth to make a screen that fits over your wheelbarrow.Always be sure to add a layer of mulch over any compost you spread in the garden, so the light and air don’t kill the compost critters before they have a chance to do their magic in your garden beds.

Mulch Much

Mulch is organic matter that you put on top of your garden beds and pots, up around the base of the plants. It can be anything from leaves, compost, or straw to cardboard and newspaper. Nature mulches herself naturally with every falling leaf, so mulching is one of the best things you can do for your soil because it keeps moisture in, protects soil critters, and can help stifle unwanted weeds. Mulching is fun and easy; I would much rather walk around the garden tossing mulch onto the beds than swing a hoe or crawl around with a weeding tool.

Maintaining a thick perpetual mulch will reduce work and increase soil health. It will prevent erosion, add diversity to the soil community, and provide nutrients for the plants. An extra thick mulch can prevent freezing in the winter and keep the soil from drying out in the heat of summer. Mulching provides an important outlet for surplus yard debris such as leaves, uprooted weeds, and bedding straw if you have animals. Mulch can also provide habitat for slugs, and it doesn’t really prevent aggressive perennial weeds such as couch grass or bindweed. Still, the good outweighs the bad in most situations, so don’t let these small drawbacks deter you.

The fastest and easiest way to convert a lawn into a garden is by sheet mulching it. Sheet mulching works in much the same way as the compost method I described above, except that you don’t build the pile as high and you spread it over a larger area. You can sheet mulch the whole yard and design garden beds later, or you can build mulch in the shapes of the beds and leave grass paths between. Here’s the basic procedure:

Mow the grass as low as possible and use a digging fork to punch in some aeration holes through the area where the mulch will go. Lay sheets of corrugated, nonwaxed cardboard over the bed areas and run a sprinkler over them for a couple of hours.

When the cardboard is soaked through, cover it with about two feet of debris. Because the piles won’t be built as high as compost piles, it is better not to use funky, rotty stuff like kitchen scraps—save those for the compost piles. Instead use straw, dead leaves, newspaper, and wood chips, and layer in manure and fresh chopped up weeds to heat it up. Layer the bumpy, ugly stuff on the bottom, using the same 25:1 brown- to-green ratio as you would for making compost.

For the final layer, use something that you find aesthetically appealing. No one wants to look at a front yard full of cardboard, but if it is hidden then it will serve its purpose without ruining your view. Some people use landscape cloth, carpeting, or plastic under their beds, but I don’t recommend these materials for any sort of food garden because they are ugly and often toxic and can create a potential nightmare for any future gardeners who try to dig or till and come up with a truckload of twenty-year-old shag carpet.

You can plant right into a fresh sheet mulch. Sow seeds and plant small starts into the top layers, or punch a hole through the cardboard to make room for the bigger roots of trees and perennials. If weeds come through, pull them out or just mulch right on top of them. When you want to add new plants, push some mulch aside and stuff them in.

Alternatively, you can use cardboard or an old piece of carpeting to cover an area temporarily, killing off grass and weeds, then pull it up and build garden beds. This saves hours of weed- and sod-removing labor. Unlike polyester carpeting, cardboard biodegrades quickly, can be tossed into the compost when it gets too soggy for reuse, and doesn’t leave fuzzy little plastic things all over the garden.

Where to Get Mulch and Compost Materials

I recommend stashing large piles of mulch all around the garden, in unused corners or in future garden beds. Here is a short list of places to get free mulch and/or compost materials for your garden beds and stockpiles.

The City. Many cities offer autumn leaf collection programs in which they pick up yard debris from residential curbsides and take it to a central dumping site. That debris, which is usually a lush mix of leaves from all over the city, is often available to the public.In Eugene, where I live, you can sign up on a list and the city will actually deliver the leaves to your driveway, free of charge. In other places there are dumping yards where locals can bring a truck and load up. Ask your local parks department what it has to offer. It may also have debris from park maintenance, such as grass clippings and tree prunings, or even extra plants. The only problem with these options is that you cannot guarantee the materials will be free of toxins. Alas, it is a toxic world, and we can only make best use of the resources we have available. Strive for balance and your garden will respond accordingly.

The Curb. Most people, especially in the suburbs, do some form of yard maintenance, which generates debris. In places where the city does not pick up yard debris from curbsides, people often send it to the dump. This is a terrible waste, some of which you can thwart by picking it up yourself first. Ask the homeowners or don’t; sometimes it’s really not a problem to just cruise around and load stuff up. Try going out on a warm Sunday afternoon when everyone’s been out mowing all day.People will usually thank you for the favor, and you will have better soil. You can also make arrangements with neighbors beforehand and have the truck ready for them to dump into. Or just put a sign in your front yard that says NEIGHBORHOOD LEAF DROP-OFF and see what shows up.

Tree Services and Landscapers. Most arborists and landscapers generate truckloads of organic matter daily, and many will even pay you to let them dump it at your place. More often they’ll chip it up and leave it for free. If they won’t chip it and have only large debris to offer, maybe you can build “hugelkülture” or use it for firewood. Just look through the yellow pages and on the Internet, call around, and make notes of what you find. It won’t take long to accumulate a list of great resources. Most landscapers also have tons of surplus plants that were pulled out of one landscape but will survive if planted into another. Ask them to drop off a few of these leftovers when they bring the chips.

Restaurants and Grocery Stores. All types of food merchants have food waste that usually goes into the trash. Choose the organic sources first, asking them to save their food scraps in buckets (which you can provide, if need be). Most places are happy to accommodate. Other places just fill up dumpsters out back— big metal gold mines of garden fertility. Pull up a truck and shovel it in, and don’t forget to wear rain pants and rubber boots so you don’t slime your clothes.

Trash and Recycling. Food places aren’t the only spots in town with dumpsters full of compost and mulch materials. Look in alleys, behind the mall, in school and church parking lots, and all through residential areas for useful garden and soil building materials such as cardboard, bags of leaves, bricks, newspapers, and more. You will probably find lots of other fine stuff as well—many people make a good living from just finding stuff in the trash and putting it to use.

Fairgrounds and Event Sites. Every year the Oregon Country Fair uses bales to mark off parking areas in a big field during the event, which lasts for only three days. The bales then rot in the field until the following year, when they are replaced by fresh ones for the next event. So each year after the fair we take the farm truck down to the site and load it full of free straw and hay bales. We usually get enough to supply our needs for the year, a truckload or two, which is about two hundred dollars’ worth of good, barely used hay and straw. Look around at local events for materials like this that are in temporary use and may go to waste, then ask the organizers if you can take them, or just drop by at dumping time and see if you get lucky.

Dairies, Hatcheries, and Ranches. Look for local sources of manure and bedding materials from places that keep animals. Visiting these places can be a difficult but enlightening experience, and I strongly recommend that you choose ones that meet organic standards and that treat their animals very well. Ask around or look in the phone book, and don’t be afraid to ask the farmer/rancher about the living conditions of the livestock.

Hugelkülture, Large Debris, and Trench Mulching

Large debris, such as branches, stumps, and rotten or scrap lumber, can be buried to provide underground habitat, store surplus water, and reserve nutrients for soil communities. Hugelkülture (pronounced HEW-gull-cool-tour) involves digging a shallow pit in the shape you want the garden bed to be, then piling in debris to ground level. Use wood up to two inches in diameter, and try to break up the pieces so none is more than three feet long or so. Then add a foot or so of soil and mulch on top, and fill the resulting garden bed with plants that like well- drained soil.

The hugelkülture area will seem to need extra water, but below the surface it will act as an underground sponge, catching and holding water to share later with nearby areas. As the buried wood decomposes, it may tie up soil nitrogen for a while, so it is best not to plant heavy-feeding annual vegetables (broccoli, cucumbers, squash) in a hugelkülture for the first year. Instead try potatoes, tomatoes, beans, or salad greens, and don’t forget to add some good perennial fruits and berries. Hugelkülture works great for starting perennial beds in odd shaped, sunken, or infertile areas, and it helps generate a closed loop system by providing an onsite outlet for large debris.

Similar to hugelkülture in principle is a technique that I call trench mulching. Trench mulching also catches and stores water in the soil, but instead of digging pits, you dig trenches about two feet deep. The trenches need be only as wide as the wood you plan to bury, and unlike hugelkülture you can trench mulch with wood of any diameter.

Cover the trench mulch with a thick layer of garden soil to bring it to just above the ground level, and then plant it.

This technique works especially well around the edge of an orchard or garden area, and the large chunks of wood will hold water for many years to come. However, larger wood ties up more nutrients during decomposition, so stick to cover crops and other plants that need less nitrogen to grow.

Tilling, Plowing, and Double-Digging, Oh My!

Plowing damages soil communities in several ways. It kills fungi and chops up larger critters such as worms and beetles. Heavy machinery compacts the soil, which leads to water-logging, erosion, and anaerobic conditions. Disregard of these facts by industrial farmers has left us with only about 5 percent of the original topsoil in the United States, and it has been said that the plow is to the prairie what the chain saw is to the forest. Just a few years of overtilling can destroy topsoil that nature took thousands of years to build, and once the soil is damaged it is difficult to repair.

You cannot improve soil just by mixing it all up—the nutrients in the subsoil become available only gradually as soil life works its way down. If you mix in too much of the heavy, clayey subsoil, many of the organisms that thrive in your topsoil will die. The best way to increase the depth of your topsoil is to build community—that is, add organic matter, such as mulch and compost, to the surface and let the critters do the rest. It is possible to dig or till garden beds, in moderation, and still maintain a wonderful tilth, but a single mistake can take many years to repair, so be very careful in this regard.

Tillage is a huge topic among farmers and gardeners everywhere, and I won’t get into all the different types of equipment out there. Generally I recommend using no-till techniques such as mulching and composting, especially in urban settings. Still, in some circumstances— especially in large areas with fertile soil—it makes sense to till or dig beds to more fully tap into the resources there. Thus, here are a few pointers that will help you avoid big mistakes.

Not Too Wet. Soil tilled when it is too wet can become overly compacted, can lose valuable water holding capacity, and will be more likely to erode when the wind and rains come. If water pools on the surface, or if the soil’s muddy enough to clump together, it’s too wet. Wait.

Not Too Dry. Dusty topsoil will blow away in even the gentlest breeze, so make sure there is some moisture in the soil before you turn it. To be worked up properly, the soil should be moist but not soggy, should hold together but not clump, and should not be dry enough to blow away—think dust bowl and avoid it! It should remind of you chocolate brownie batter, and you should be able to squeeze water through it like a sponge.

Not Too Often. Some gardeners become addicted to tilling and want to run the machine over every little weed that pops up. As with all technology, use tilling as little as possible. Manual weeding is good for your body and better for the soil.

Not Too Deep. The rare occasion calls for deep tilling, or subsoiling, but this is a call best made by experts. Just try to knock back the weeds and get some fluffy soil to add mulch and seeds to; you’ll be on your way.

Mulch or plant cover crops quickly onto bare or tilled ground, or the weeds will sprout and try to cover the naked soil. Some gardeners till often, incorporating weeds and mulch into the soil and building fertility that way. Others prefer to till only when first establishing an area and maintain a deep mulch from then on. Still others will till up an area every few years and mulch or hand-work the area, or leave it fallow between. Experiment—though cautiously—and try to find a balance so that you are creating the least amount of disturbance for the greatest beneficial effect.

There is a small-scale technique called biointensive gardening, developed by organic gardening experts Alan Chadwick and John

Jeavons, that involves double-digging fluffy beds by hand, then maintaining them with deep mulch and cover crops. This technique is an excellent way to grow a lot of food on a very small plot of land.

I rarely double-dig anything myself, preferring naps in the hammock and less strenuous approaches like sheet mulch to such hard work. Further, it is essential to accompany double-digging with the other strategies in biointensive agriculture, such as cover crops and detailed rotations, so don’t just go out and excavate a huge hole without learning the technique. I do not include instructions here, but if this interests you be sure to read the books by John Jeavons, listed in the back of this book.

Maintaining and Improving Living Soil

Once you’ve established garden beds you’ll need to consistently add organic matter to the soil to replenish the nutrients used by your crops. In a closed loop system the rule is one calorie in for one calorie out, and in a truly beneficial system you should improve the soil even beyond just replacing what you take. Here are some good strategies for maintaining and improving organic soil.

Fertilizers and Amendments. Many farmers and gardeners use manufactured “organic” fertilizers and amendments as their primary tools for building soil. These inputs, usually made of mining and meat industry by products, can indeed boost a yield and help create a lasting fertile soil. However, while fertilizers can help provide a short term fix for this season’s deficiencies, they should always be accompanied by a long term soil building strategy that includes several or all of the other strategies described here.

For giving plants a light boost, try a simple 3–1–1 mixture of fish meal, rock dust, and kelp, respectively. You can use this mix all over the garden: when transplanting, as a side dressing, and mixed into potting soil. I am not big into fertilizers, preferring good old fashioned compost, but the 3–1–1 seems to work really well and is relatively low input. To determine what is best for you and your soil, ask around to find out what works for the other organic gardeners near you.

When choosing to buy fertilizers and amendments, think of where the resource comes from and try to tap into the waste stream wherever possible. Again, if we embrace the goal of creating a self perpetuating ecosystem, we will see purchased fertilizers and amendments as last resorts, to be used only when other options are not available.

Jauche. Pronounced YOW-kuh, and also known as nettle tea, jauche makes a great fertilizer for young plants. Stinging nettle regulates iron for plants and can help prevent or eliminate pest invasions. Add two pounds of fresh nettle greens to two gallons of lukewarm water. Let this sit and steep for twenty-four hours, then sieve and spray on leaves. Use the leftover sludge as a mulch around perennials. Spray as often as twice a day for diseased plants, or dilute and use periodically for a general health boost. Many gardeners make similar concoctions using comfrey, mullein, tomato leaves, and other plants, with varied effects. Try some and see what works for you.

Compost Tea. Made by aerobically fermenting finished compost in water for twelve to twenty-four hours, compost tea boosts fertility on both organic and conventional farms. Proven to overcome and prevent disease and to increase the diversity and vigor of soil communities, compost tea is an essential component of a truly ecological agriculture. Store bought brewers can be very expensive, but it is important to make the tea correctly. Consider going in on a brewer with a local garden club, or find a local source of surplus compost tea. A garden center near you probably has extra tea available every week when it cleans out the brewer.

If you don’t want to mess with big machines, make your own cold water tea brewer with a five-gallon bucket and a small pond pump (solar powered is best). Fill the bucket with rainwater and dangle an old sockful of compost over the edge, so the sock acts like a tea bag. Submerge the pump and turn it on. In twenty-four hours your tea is ready to use.

Or make humus tea. The rich, spongy soil generated on the wild forest floor is called humus, and it is the absolute best-quality soil around. It is easy enough to build humus at home through composting, mulching, and the other methods described here. If you can mindfully harvest some good humus from a natural area nearby, then bring home a bucketful, dilute it with fresh water, and sprinkle it on your soil and compost piles. The microorganisms you import will enhance the diversity of your existing soil community and speed up the beneficial processes.

Biodynamic Compost and Soil Preparations

Often described as “homeopathic fertilizers,” these magic potions are much more than herbal remedies. In 1924 clairvoyant scientist Rudolf Steiner gave a series of lectures to the farmers of Europe about the most ecological, sustainable ways to grow food. He put forth the following recipes—infusions of plant, animal, and cosmic energy—and claimed they would help restore balance to the soil and promote optimum fertility on the farm.

Since then biodynamic compost preparations, joined by three field and foliar sprays, have proven themselves time and again as highly effective, organic inputs. Biodynamics is a whole field of agricultural study, but the preps are useful to organic gardeners of all sorts. These preparations are usually identified by the numbers 500 through 508, as indicated below. I will do my best to describe, briefly, each one:(6)

500: Horn Manure. Made by filling a cow horn with cow manure and burying it over the winter, then digging it up and mixing a small handful into five gallons of water and stirring for an hour (see below) as the sun sets. The liquid is sprinkled on the soil and around the farm or garden using your fingers, a paintbrush, or a small broom. This promotes root activity, stimulates soil life and increases beneficial-bacterium growth, regulates lime and nitrogen, helps in the release of trace elements, and stimulates seed germination.

501: Horn Silica. Made by filling a cow horn with ground quartz and burying it over the summer, then digging it up and mixing it with water, stirring for an hour (see below) as the sun rises, and sprinkling it on foliage, branches, and buds. Horn silica enhances light metabolism of plants, stimulates photosynthesis and the formation of chlorophyll, and influences the color, aroma, flavor, and keeping qualities of crops.

502: Yarrow. Made from yarrow flowers stuffed into a stag bladder and hung in the sun for the summer. The flower substance is then removed from the bladder, and a teaspoonful is put into a hole in the compost pile. Preparation 502 assimilates potash and sulfur and helps plants attract trace elements. 503: Chamomile. Made from chamomile flowers stuffed into a cow intestine and buried over the winter. The little sausages are then dug up, and the substance inside is added to a second hole in the compost pile. This preparation assimilates potash and calcium, allows plants to take in more nutrients, stabilizes nitrogen, and increases soil life.

504: Nettle. A pouch is made from peat moss, filled with stinging nettle leaves, and buried over the winter. The decomposed nettle is removed and added to a third hole in the compost pile. Nettle helps plants access remote nutrients and balances iron and nitrogen.

505: Oak Bark. Made by filling a cow skull with white oak bark, burying it over the winter, and then digging it up and adding the resulting substance to a fourth hole in the compost pile, 505 helps combat harmful diseases and moderates the whole compost ecosystem for optimum health and performance.

506: Dandelion. This preparation is made by stuffing dandelion buds into a cow mesentery, burying it over the winter, and then digging it up. Add 506 to the fifth and last compost hole. This stimulates a relationship between silica and potash and attracts cosmic forces into the soil.

507: Valerian. Make this final compost preparation by squeezing valerian flowers through some cheesecloth into a brown glass and fermenting for one year. The juice is diluted with water and stirred for ten minutes (see below), then sprinkled on the top of the compost pile after the other five preparations have been inserted into their respective holes. This seals the pile and stimulates the effective use of phosphorus by the soil.

508: Equisetum Tea. Another kind of jauche, this tea is used to treat and prevent fungal disease. Combine one part equisetum (horsetail) with ten parts water. Bring to a rolling boil, then reduce the heat to a fast simmer and let simmer for fifteen to twenty minutes. Turn off heat, cover, and leave for seven to fourteen days in the dark to ferment. The fresh lemony fragrance tells you that it’s done. Dilute 10:1 with water, stir for twenty minutes (see below), and sprinkle over the leaves of fruit trees, squashes, tomatoes, grapes, and anything else that is susceptible to blight, powdery mildew, rust, or similar problems.

Use a similar recipe to make a tree paste: Prepare equisetum tea as above and mix with cow manure, clay, and diatomaceous earth. Paint from the base of the tree to a foot out on the first few branches to protect the bark from sunscald and disease.

Stirring the Biodynamic Preparations.

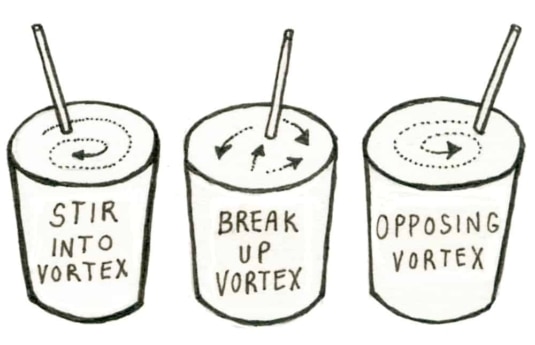

Place a portion of the preparation into a five-gallon bucket of rainwater or piped-in water that has been left out for a day to allow the chlorine to evaporate. Using your arm, a wire or wicker whisk, or a stick, begin moving the water around in a circle. Keep going at a steady rate until you see a strong vortex form in the water, spiraling down like a mini tornado into the bottom of the bucket.

Now switch directions, breaking the vortex and starting over in the other direction. Keep going back and forth like this for as long as the preparation calls for. The valerian compost preparation mentioned above needs to be stirred like this for only ten minutes, but the two field sprays (horn manure and horn silica) require an entire hour of continuous stirring. Stirring the preps is most fun when done by a team of two or three people, handing off the bucket when arms get tired, and it is a great way to spend intentional time with your fellow gardeners.

Animal Inputs

Some people like to mix up manure teas by tossing some good organic poop into a barrel, adding a bunch of water, and letting it sit for a day or so before diluting it and dousing the soil with it. Manure and manure tea are valuable additions to any compost pile or sheet mulch and are the primary input relied upon by many organic farmers and gardeners around the world.

It is helpful to use manure of all kinds, but do not become dependent upon it or any other single component for soil building; also, as with all inputs, always apply sparingly. Alpaca and rabbit manure can be used relatively fresh, whereas cow, chicken, and horse manure should be composted for at least a year before being used. Again, use onsite or recycled sources wherever possible. Most dairies and chicken farms are happy to get rid of surplus manure, and many will even dump a load into your truck for you with their tractor.

Manures and other animal inputs such as feathers, eggs, and dairy products, as well as the animals that produce them, add value, richness, and fertility to an ecosystem. Realistically, no piece of Earth can thrive without some sort of animal influence, and no whole system design is complete without using the surpluses generated by the animals onsite.

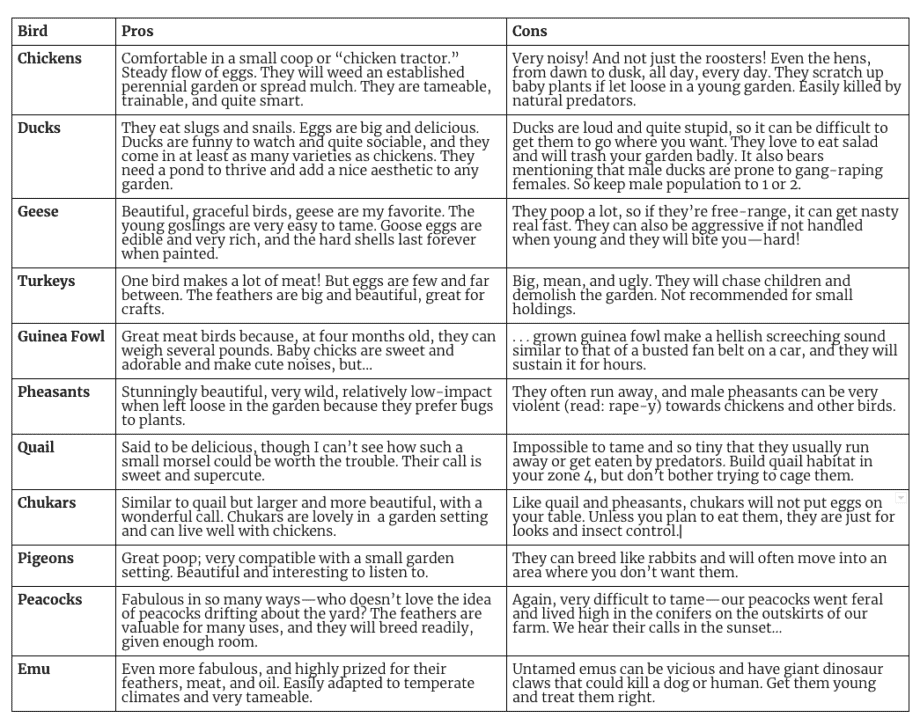

We love our chickens and geese; they add character and entertainment to the homestead, eat weeds and slugs, and sift and manure our mulch for us before we add it to the garden beds. Interacting with these and the other animals on our farm brings us closer to nature and brings our farm closer to a closed loop fertility cycle.

Pros and Cons of Barnyard Birds

Some folks are disturbed by any sort of domestication and/or use of animals and animal inputs, for various reasons. There are many farms and gardens that thrive without animal inputs at all, such as Bountiful Gardens in Willitts, California, where folks advocate using one-third of agricultural land for growing plants to build compost, which will replace the nutrients lost to crops. Like many of the strategies in this book, this works very well in some circumstances and is impractical in others.

Human Waste

Some of gardeners use the waste products produced by the humans onsite, namely urine and humanure. Urine and humanure are local, basically renewable resources that do not involve the processing, packaging, and transport that even the most benign organic fertilizers require. Using human waste is a highly effective yet controversial soil building technique, made less intimidating with just a little information.

I’ve heard that if you have ringworm or athlete’s foot or sustain an injury in the wilderness, you should pee on it. In the garden fresh urine can be diluted 1:10 with water and poured on the soil or compost pile; a single human produces enough urine to fertilize about three thousand square feet of garden soil a year.(7) Don’t put it directly on the plants, because it may burn the leaves, and in fact urine has been used by some people at full strength as an effective weedkiller. Use urine as fresh as possible to avoid the foul odor that comes after a few days of fermentation.

As for feces, also known as humanure, they should be collected and composted in a separate compost pile for a year, after which they can be added to fruit trees or perennials as a mulch. Obviously you will get a much higher quality product if you choose a vegetarian, organic diet. With some basic precautions such as frequent hand washing and long term composting, our own solid waste can become a free, nutrient rich input to the garden. See the resources section for references to more information about integrating human wastes, safely, into your whole system design.

Vermiculture and Vermicomposting

Earthworms might be the hardest working creatures on Earth, and a natural agriculture is dependent on their constant churning, eating, and releasing of soil and organic matter. Their manure, or castings, is rich in essential plant nutrients as well as a plethora of microorganisms and is one of the best fertilizers there is.

A simple worm bin will fit under the kitchen sink, makes a great educational tool for children and adults alike, and is easily built from recycled materials such as an old wooden dresser.

Detailed information about the varied methods of vermiculture (growing worms) and vermicomposting (using worms to make soil) is readily available on the Internet and at public libraries, so I’m not going to be too redundant about it here because I’m no expert on this one.

Cover Crops, Pioneer Plants, and Detoxifiers: Plants as Fertility

An excellent way to improve soil and build long term fertility is by planting cover crops, which suppress weeds and add organic matter to the soil. If you leave an area of bare soil, nature will cover crop it on her own with a diversity of wild weeds, so why not plant beneficial soil builders instead? The best cover crops are polycultures—mixtures of plants that interact with one another to provide the optimum soil building performance.

Start with a nitrogen fixer, which works with bacteria in a symbiotic relationship to fix atmospheric nitrogen and make it available to other plants. Most plants in the bean family (Fabaceae) have this ability, such as clover, fava beans, vetch, and kudzu. Other plants that can fix nitrogen include alder, autumn olive, sea buckthorn, and ceanothus. Add a grass like rye, millet, or oats to send roots deep into the soil, break up any hardpan, and bring nutrients to the surface. Feel free to mix in some good habitat and forage plants, such as buckwheat and wildflowers, to encourage bird and insect populations and provide flowers for the table.

As the cover crops mature, mow them a few times to increase the vigor and soil building power of the plants. Add the mowings to the compost pile or use them for mulch. When you are ready to garden the area, either mulch or till it up and fill it with your garden plants, or just work up small sections and insert the new plants, leaving a living mulch of mowed cover crop all around.

If your soil is especially bad or you have problems with erosion or toxicity, consider adding some pioneer plants, which grow well in damaged soils and can help establish a garden space in an otherwise barren area. Pioneers stabilize and improve soil and, once established, provide shade and habitat for successional plant and animal species. Many pioneers are trees, which you can later cut down and use for fuel, construction, or chip mulch. Some useful pioneers are sycamore, alder, birch, poplar, and nitrogen fixers like tree lupine, locust, and buckthorn.(8)

Toxic areas need to be cover cropped before being used to grow anything edible. If you suspect toxicity or are unsure of the history of the

site, add detoxifying plants to the cover crop mix. Sudan grass and alpine pennycress are fine detoxifiers, as are many kinds of mushrooms.(9) Pumpkins are also good; you can grow jack-o’-lanterns and carve them up for Halloween. Don’t eat detoxifiers, for obvious reasons. When you grow pumpkins or other types of squash for food, do so on clean, fertile soil to avoid ingesting any toxins they may pull up.

Crop Rotations and Fallowing

Monocropping, or growing too much of the same thing, can damage soil by depleting too much of one nutrient or harboring disease and pest populations. Because disease causing organisms can survive in the soil long after the plants have died, and because different plants use different nutrients, it is important to rotate the types of plants you grow through different parts of the garden.

This is especially true with annual vegetable crops, which are often heavy feeders and can rapidly deplete a fertile area unless a diversity of crops are rotated through. It is equally important to let every piece of ground go fallow (lie unused), or to plant it with cover crops, for at least one growing season every few years. Taking good notes each season helps facilitate good crop rotations, and Eliot Coleman’s book Four Season Harvest includes excellent recommendations for specific rotational patterns to use.

Seeds as Fertility

Every inch of topsoil contains hundred of tiny seeds, from the gamut of common weeds to the welcome volunteers that seem to come from nowhere, offering a tasty surprise. Adding seeds to your garden soil is one of the best ways to enhance the fertility of your garden. If you save seeds, put the chaff and leftovers from cleaning them into the compost or use them as mulch, and you will see a rapid increase in the diversity of volunteers that come forth. If you have leftover seeds from the season’s growing, empty the packets into your compost or make seed balls, using the recipe in the next chapter.

Above all, remember that there is no one best way to build soil—you must combine and vary your methods according to your specific conditions. Take the time to learn about these conditions and to develop a soil building strategy that meets your needs. Apply different techniques according to their function and relative location and application, and use varied combinations to optimize opportunities to make your garden grow.

Dirt Worship

We know that organic soil depends on vast, thriving communities of insects and macro and microorganisms. Yet thousands of products line the shelves of every superstore in the world to help us kill plants, bugs, and bacteria.

Because we fear germs, weeds, and wildness, we poison everything around us, and ultimately ourselves, in our quest for health, purity, and control. Just walk into to any conventional garden center and you will be bombarded with the sickening smell of industrial poison.

Nature, which we are of course a part of, is packed with germs, bugs, and living creatures, all of which have an essential place in holistic, healthy cycles. On our own skin and inside our bodies live thousands of species of bacteria—reproducing, dying, consuming one another, and supporting the bodily functions that keep us alive. If we were to sterilize everything (and don’t think Clorox isn’t trying), we would surely perish.

Likewise, if we nurture a thriving ecosystem wherever possible, we too will thrive. When we encourage, rather than discourage, the growth of plants, animals, insects, and bacteria, we immediately increase our ability to thrive on planet Earth. We can begin to heal our relationship with nature when we overcome our fear of the dirt.

If you want to garden you have to get dirty. Many nonorganic gardeners try to avoid this at great expense to themselves and the soil community. They wear gloves and knee pads, spray weeds from ten feet away, set up intricate self-watering systems, and occasionally toss some fertilizer or mulch from a plastic bag onto the soil. People fear the dirt, but rarely will dirt make you sick. On the contrary, exposing ourselves to a diversity of life makes our bodies and immune systems stronger, better able to fight disease.

It is totally possible to grow a lush organic garden without straining your back, but the first step in getting reacquainted with the land,

organically, is to overcome our fear of dirty, yucky things and allow ourselves to get grubby with the grub worms. As we conquer our fears we open to nature, and dirty work becomes a real adventure.

Get Planted

Someone once told me that the knowledge of how to thrive on the land is free and available to anyone who puts her hands into the soil. This means we each have the natural instincts to thrive as a species, within the life web on Earth. In this modern age of fast paced electronic consumerism and global violence, however, many people have lost touch with their natural instincts. A fun way to regain some of these instincts and get reacquainted with nature is to let a friend plant you in the garden.

Dig a hole one to two feet deep (perhaps this will be one of your test pits from earlier). Now get in the hole with your bare feet. Feel the cool dirt beneath your toes and imagine sending roots deep and wide under the entire garden, all the way to the center of the earth and through to the other side. Use all your senses to hear, smell, taste, see, touch, and intuit the life in the soil. Wrap your mind around the idea that all life depends on this tiny community.

Now have a friend pile in soil all around your feet and ankles, or up to your knees if your hole is deep enough. She should treat you like any other plant—packing the soil in well but not too tightly, adding mulch on top, and watering you in when she’s finished.

While she plants you, raise your arms to the sky and imagine your leaves and branches unfolding, expanding toward the heavens. Close your eyes and imagine blooming, setting seeds, wilting, and returning to the earth. When you’ve had enough ask your friend to dig you out and switch roles. It may seem silly, but this is a truly transformative experience if you give it the chance.

Your relationship with the soil will grow and change as your garden does, and as you become more in tune with the natural cycles of the earth. Now we come to the most colorful, fragrant, and delicious part of the garden—the plants.

Notes for Chapter 4

- Chris Roth, “Gardening, Diversity, Peace and Place: An Interview with Alan Kapuler,” Talking Leaves (1999).

2. Geri Welzel Guidetti, “From the Ground Up,” in Build Your Ark! How to Prepare for Uncertain Times (Oxford, OH: Ark Institute, 1996).

3. Sir Albert Howard, The Soil and Health (New York: Schocken, 1972), 22.

4. Soil Foodweb, Inc., www.soilfoodweb.com, October 2003.

5. Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, Weeds and What They Tell (Springfield, IL: Biodynamic Farming

and Gardening Association, 1976), 10.

6. Sources for biodynamic preparation descriptions: Beth Weiting, lecture delivered to Oregon Biodynamic Conference, 2001, and a flyer by the Josephine Porter Institute, Woolwine, VA, 2001.

7. Elaine Myers, “Pee on the Garden,” The Permaculture Activist (May 1992).

8. Ken Fern, Plants for a Future, 3rd edition (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2000), 21–25.

9. Paul Stamets, www.fungiperfecti.com, October 2003.