“First, know food. From food all things are born, by food they live, toward food they move, into food they return.”

—Taittiriya Upanishad

Plants for the Future

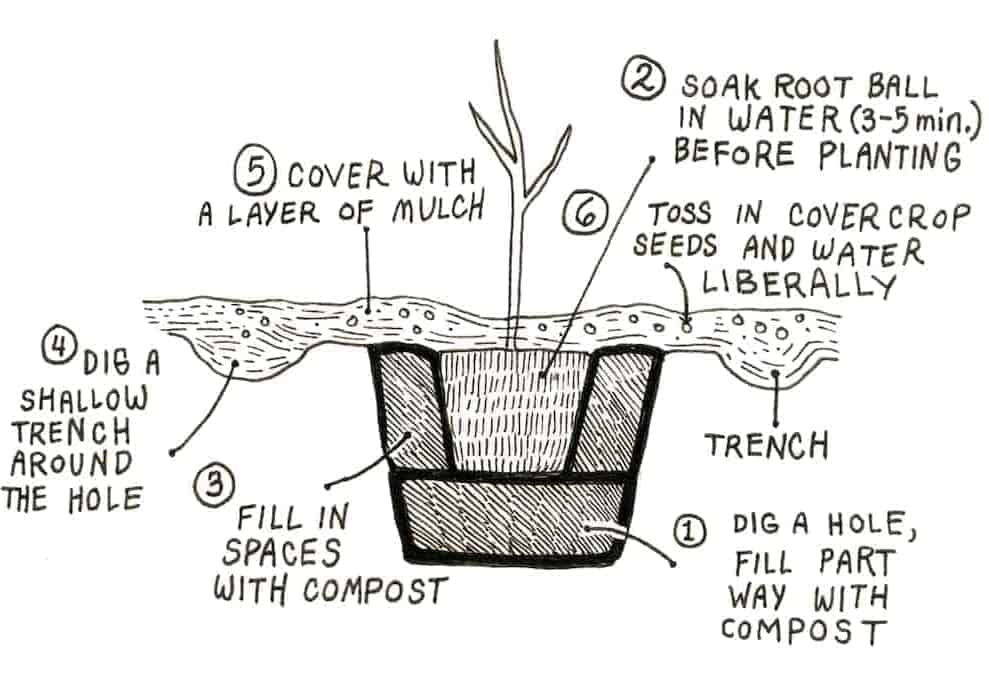

When you say “garden,” most people think first of plants, but all gardens ultimately depend on the quality and quantity of soil fertility and clean water. I don’t recommend planting anything except cover crops while you’re still designing the basic bed layout and water flow through your garden. I have seen many a garden die because the gardener didn’t properly prepare the soil and establish a reliable water supply. Once you’ve established this basic fertile infrastructure, you are ready to put some plants in the ground!

Whether we live on a farm and grow our own food or live in an apartment in the city and have never planted a seed, we need plants. Plants provide almost all our food and vast amounts of our fuel, fiber, and medicine. Plants filter the air and water and help bind together the cycles of the earth.

Learning about plants inspires an instinctual, natural awareness that leads to increased creativity and mental and physical healing. Plants provide opportunities. The more diverse the plants, the more diverse the opportunities.

Biodiversity and Food Security

The average person in the United States knows over a thousand corporate logos but only ten species of plants.(1) Well, what if we ditch the corporations and learn how to interact with more of the nonhuman species around us? Could we then increase our capacity to steward the land, provide for our needs, and nourish the other species on Earth? You can reap great rewards by growing and knowing just ten species of plants—imagine the benefits of knowing and growing a thousand.

In nature you will rarely find more than a few square feet of just one kind of plant. But in conventional agriculture, and many home gardens, large patches of just one species, also known as monocultures, are the status quo.

The tragic Irish Potato Famine in the mid-1800s occurred because only two varieties of potatoes were growing in the whole country—both susceptible to potato blight, a disease that devastates crops. Both crops failed when the blight hit hard one year, leading to major food shortages nationwide. Farmers did not know or think to diversify their fields—they thought only of the potato that would allegedly provide the best yield, and as a result they lost it all. Ironically, just across the sea hundreds of potato varieties, many of which were probably blight-resistant, were growing all over North, Central, and South America.

There are many lessons to be learned from this type of tragedy: Don’t grow just one or two varieties of anything, don’t grow the same thing every year, and don’t base your food security on just one, two, or even fifty species. If we embrace biodiversity—and more, seek out and perpetuate it—we will directly increase the longevity and quality of our own lives and those of our species.

By encouraging an ever widening array of plants, insects, and microorganisms, we can design and create gardens that are beautiful, diverse, functional, and teeming with life. Conversely, if we pillage the gene pool until only those species with immediate economic value remain, then we may destroy our chances of long term survival on planet Earth.

The importance of diversity in our lives and gardens is apparent in everything we do, and by maximizing plant diversity in our own backyards we enhance the diversity of our ever connected planet. So far we have seen how to establish a diversified system for making best

use of our water resources, and how to cultivate a diverse soil community. Next, we will see how to establish diverse gardens that will nurture us—and the earth—for generations to come.

Your paradise garden should host as many different plants as possible. But not just any plants. Many plants will easily outlive the gardener, and all, if left to their own devices, will propagate themselves in perpetuity, given the right conditions at the outset. Therefore, it is crucial to choose each plant and its placement carefully and with a vision of the larger, long term ecological cycle. Plants are at the core of a healthy bioregional ecology, so let’s look at the most ecological ways to bring them into your landscape and your life.

Plant Guilds and Polycultures

One of the most essential strategies for building long lasting, low maintenance paradise gardens is the use of plant guilds, or polycultures, which bring together plants that help one another to thrive. Though some gardeners differentiate between the two, with guild meaning a specific group of mutually beneficial plants and polyculture referring to the larger, diverse garden full of guilds, I will use both terms interchangeably here.

A well planned polyculture will yield year round, providing food, seeds, and compost crops for people, wildlife, and microorganisms alike. Because they are so diverse, polycultures tend to yield more and require less maintenance than monocultures, and they are much less susceptible to disease and insect infestation.

Typical vegetable gardens focus on annual or biennial plants, which die after a year or two, but a polyculture will contain from three to fifteen different plants and should include trees and long lived perennials among the vegetables. This is more akin to nature’s gardens, in which the older, larger plants shelter and support the tender annuals.

Like the rest of an organic garden, a plant guild works with nature rather than against it—mimicking nature rather than trying to overpower it. The guild, once established, will take on its own successive cycles, in which the inhabitants regulate themselves. You can then introduce new species when you choose, based on the ongoing needs of the whole garden.

Native tribes in North and South America have long practiced polycultural gardening, such as in the traditional Three Sisters corn-beans- squash combination. In this example corn is the staple crop, a heavy feeder that needs fertile soil. Beans fix nitrogen, add a second crop, and utilize vertical space as they climb up the sturdy cornstalks.Squash provides a third crop as well as a shady ground cover to keep the soil moist. Sometimes a fourth sister is added: cleome, also known as spider flower. Cleome is aromatic with a magnificent flower; these traits attract beneficial pollinators, and the spiny stems deter would-be marauders from ravaging the corn patch.

Revolutionary Japanese farmer Masanobu Fukuoka presents another classic example with his “Natural” farming technique. Fukuoka grows a mix of rice, barley, and clover on his farm and uses complex guilds in his orchard with hundreds of varieties of plants. He grows many varieties of evergreen and deciduous trees including nuts and fruits; adds soil builders such as clover, alfalfa, vetch, lupine, and soybean; and plants grasses and perennials below them, to shelter and support tender annual vegetables.

He also grows multifunctional shelterbelts, sometimes called hedgerows, which provide windbreaks, produce food, and attract beneficial insects. He uses no fertilizer or pesticides and a minimum of labor and water, yet his fields yield as much (or more) grain every year as the farms around him. He attributes his success to the wildness and diversity of his gardens.

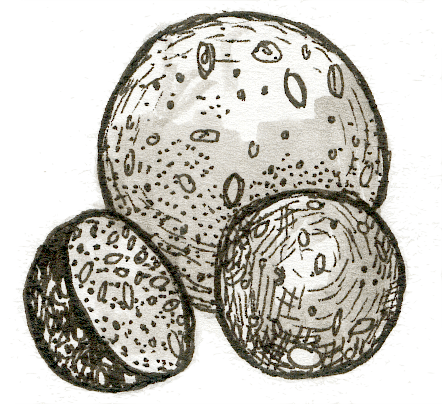

Fukuoka uses homemade “seed balls” to plant polycultures on large sections of land. These clay pellets are about half an inch in diameter and contain anywhere from three to a hundred varieties of seeds. The clay forms a protective shell to keep birds and insects from eating the seeds before they sprout. Fukuoka believes that we should sow seed balls everywhere, letting the plants decide where to thrive and where to give way to other species.

Use the recipe in the sidebar “How To Make Your Own Seed balls” to make your own. Fun to make with children of all ages, they are the fastest way to introduce a plethora of new species to home and neighborhood gardens, or to disperse and reestablish native plant species in environmentally degraded or barren sites in cities and elsewhere.

How to Make Seed Balls

This is the recipe recommended by photographer and ecological activist Jim Bones, who works with schoolchildren to revegetate damaged natural landscapes. Together they collect seeds, make seed balls, and sow them during the rainy season. The plants take it from there.

Seed balls are the fastest way to plant a wide variety of plants over a large area, and they are great fun to make. Here’s the recipe.

Seed mix: This may contain all the seeds for a complete habitat or just a few varieties for a specific combination of crops. Use from three to a hundred different varieties, depending on your goals.

Semi-dry, living compost: Do not use sterilized compost. You need the living organisms to help inoculate the soil. Choose your best stuff from the core of a finished pile and sift it. It is a good idea to mix in additional humus or bacterial inoculants to the compost before mixing up the seed balls.

Powdered red clay: A few pounds is plenty. Do not use gray or white clay—it lacks the important mineral nutrients present in red clay.

Mix one part seed mix, three parts compost, and five parts clay. Stir it around with your hands and make sure all the small clumps are broken up. When the mix is grainy and crumbly, add one to two parts water, a little at a time, until you get about the same consistency as cookie dough. Pinch off a small (half-inch) piece of the “dough” and roll it between your palms until you feel the ball tighten up as the seeds, compost, and clay lock together.

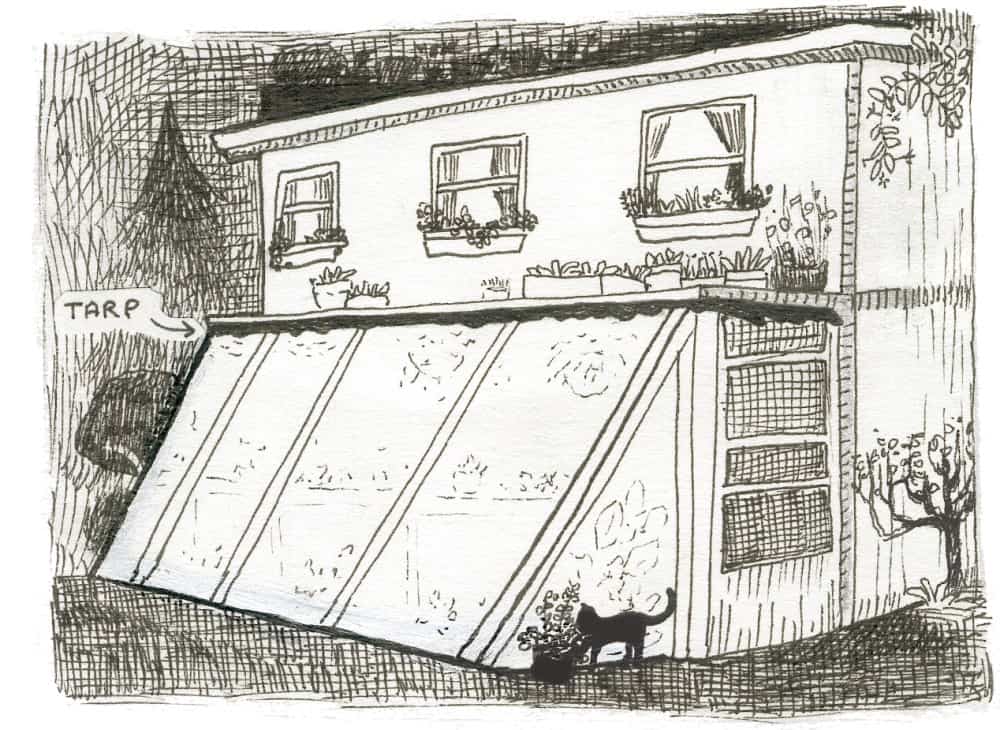

Toss the balls onto a tarp and store in a sheltered area for twenty-four hours until dry. Now you can store the seed balls in a cool, dry, dark place for up to several weeks—but it is best to use them as soon as possible, because many of the seeds may begin to sprout immediately.

Alley Cropping

Alley cropping involves growing carefully selected guilds—such as the Three Sisters example above—in lateral strips between orchard rows. Oregon organic farmer John Sundquist uses alley cropping to rotate vegetable crops through his diverse fruit and bamboo orchard. The orchard alone requires a significant amount of mowing, pruning, and mulching. So rather than grow his annuals in a separate field, he tills beds between the rows of fruit trees and sows seed mixes, with flowers, vegetables, and fiber plants.

Directly under the apple and pear trees he grows perennials such as elecampane, milk thistle, and burdock. These plants attract beneficial insects and provide a living mulch for the fruit trees, plus medicine and food for the farmer. The result is a network of diverse, multifunctional hedgerows with wide, easy-to-maintain beds of annual crops between.

The benefits are exponential: First, by consolidating the plants, John uses less water and spends less time moving around irrigation equipment. Next, when he weeds the annual beds, he throws the weeds onto the adjacent perennial beds as mulch, which holds in soil moisture and suppresses weeds.Also, because he often lets the strips go fallow for a few years after each use, he is able to maintain soil fertility with a minimum of inputs. He brings in a few cubic yards of mulch a year and sometimes applies small amounts of rock dust, kelp, or compost.

What results is a multilayered rainbow of annual and perennial herbs, flowers, fruits, and vegetables, literally vibrating in the summer sunshine, with bees, hoverflies, hummingbirds, butterflies, and a dozen other types of pollinators. Any time of year there is something to eat, and when local schoolchildren come out for farm tours they see how one person can produce large amounts of good organic food.

Alley cropping is more diverse than a simple Three Sisters–style guild and less chaotic than Fukuoka’s junglelike orchard polycultures. The linear alley beds keep the garden organized and allow for easy access for weeding and harvesting. Alley cropping works especially well in a large area, where there is plenty of space for the wide hedge-like rows. The wide paths and semi-straight rows make for easy maintenance, while the mixed crops and perennial fruits keep the row cropped landscape diverse and interesting.

In a small space such as an urban garden, however, it makes more sense to incorporate these ideas into a tighter, curvier design that includes diverse perennial borders with patches of annual vegetables between. The hedges filter wind and sun for the tender veggies and provide mulch and compost materials. You can also use hedges to create “rooms” within the garden that make it seem like a labyrinthine jungle instead of a boxed-in yard. Alternatively, remove fences between individual urban lots and replace them with diverse “alleys” of fruits, nuts, and perennials.

Multifunctional Hedgerows

by Jude Hobbs

Multifunctional hedgerows are an excellent strategy to include in an ecological garden as part of whole system design for self-reliant living. Hedgerows consist of mixed plantings that may include trees, shrubs, low growing plants, perennials, herbs, and vines. Hedgerows often grow along field borders, fence lines, and riparian zones in either rural or suburban settings. They enhance the beauty, productivity, and biodiversity of the landscape.

Hedgerows act as bank and soil stabilizers and conditioners; animal fodder; nectar sources for bees and other pollinators; habitat for pest predators, mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians; windbreaks, shelterbelts, and privacy and sound barriers; and a source of diversified income. In riparian zones hedgerows also provide shade areas that cool the water temperature. They are an ultimate opportunity for biodiversity.

Potential income producing opportunities of hedgerows include fuel wood, craft materials (such as willow), medicinal herbs, floral materials and dye plants, and seeds, rootstock, and cuttings for propagation. The leaves, berries, nuts, roots, shoots, and fungi are wonderful food sources.

One of the most useful functions of hedgerow plantings is their role as windbreaks. Wind will be affected by a planting that is only three feet high as long as it is of 40 percent density and is sited perpendicular to the wind. It can also reduce home heating costs from 10 to 40 percent. Hedgerow windbreaks can typically reduce open field wind speeds by 20 to 75 percent at distances of up to ten times their height.

The combination of function and beauty is an essential component of all landscaping. The location and size of the area to be planted will determine hedgerow design, but hedgerows are always longer than they are wide. In placement, a north–south planting direction is ideal but not essential. Whenever possible, arrange hedgerows perpendicular to prevailing winds.Although a single line of trees will provide some benefits, four or more rows of plants are best for windbreaks, water and soil conservation, wildlife habitat, and general biodiversity. When it works for the situation, place plants tallest at maturity in the center row, with shorter ones interplanted between and along the edges.

A diverse selection of plant sizes and characteristics is most beneficial. Through thoughtful observation, the design will match the site and plant characteristics. The elements that influence plant selection, again, are function, location, and size of a fully grown hedgerow. Planting hedgerows also encourages wildlife corridors. As an example, if you are interested in attracting birds, then include deciduous trees as the tallest plant in the hedgerow. Birds find it much easier to land in deciduous trees due to their open form.

Establishing a hedgerow is a long term commitment. With proper planning and care, it will take approximately four to eight years to establish the planting and thirty or more years for it to reach maturity. However, it is worth the investment. Whether in a rural or urban setting, multispecies plantings provide beneficial opportunities for everyone.

Function, Space, and Time

All these methods employ one important technique: the intentional assembly of plant communities based on the function, form, and life span of the plants. This creates an ecologically harmonious situation in which the plants, soil, gardeners, and related ecosystems all benefit at once. We can use the natural forest as a model for building guilds that layer functional niches within niches in space and time. When we plant several of these guilds together the result is a multifunctional, polycultural garden that thrives in low maintenance perpetuity.

To understand this, think of the way a forest looks: Small plants and debris cover the ground so that no soil is bare. Larger plants and shrubs grow up against small trees, and tall trees fill in the gaps to create an overstory canopy that is rich in bird and animal life. Vines wrap around the trees and drip across the skyline. Something is always sprouting while neighboring plants die or go dormant for the season, and some kind of food is always available.

The entire forest remains moist and cool even on hot days, yet cold winds and killing frost rarely penetrate the dense growth, so the interior of the forest remains temperate, while sun loving plants crowd the edges where there is more light. Every nook and niche has something to offer and is home to something or someone, so that every square foot reeks of life and diversity.

The forest is nature’s masterpiece—the climax toward which all landscapes strive. We can benefit from helping our own gardens toward this goal. By designing gardens that mimic a forest ecology, we can grow edible “food forests” that also yield fuel, fiber, medicine, and habitat and that stack functions, space, and time toward a highly efficient, low maintenance, beautiful garden ecosystem.

We’ll start with stacking functions and then see how to stack plants in space and time:

Stacking Functions

To design a polycultural garden, start by filling the functional niches that your garden and lifestyle require. First, make a list of everything you want to grow, focusing on the plants that you need to live—what you like to eat, what flowers you like, what medicinal herbs you use, and so on. This will give you a good idea of what your primary crops will be.

The primary crop is the main thing you want to get out of this particular area of the garden, and its needs are what the rest of the plants in the guild will support. For example, in the Three Sisters guild the primary crop is corn, and the companion crops are beans and squash.

Next to the name of each primary crop, write down what it might need to thrive in your garden. This could include shade, nitrogen, mulch, protection from insects, or anything else that seems pertinent. Support plants, sometimes also called companion plants, can serve a variety of functions.

Some people include at least one plant for each function in every guild, while others make specific choices based on their observations in the garden. Remember also to group the plants according to light and water needs and the type of soil they prefer.

Sometimes it helps to make a slip of paper for each plant you have or want, with its function and form, and move the slips around on a map of your garden until it all makes sense. Later you can add successive crops, which will mature and ripen after the first crops are gone. Don’t worry too much about how it will all fit together in time and space—we’ll get to that soon enough. For now we are concerned with function. Don’t plant anything yet; just start listing and assembling plants.

Below is a list of functions a plant or group of plants might serve, with common name examples for each.

Please refer to the resources section for a list of books that contain species lists and lists of specific plant combinations. My purpose here is not to give you lists of plant names to memorize but to help you determine what you want the plants in your garden to do, and to show you how to choose what to grow accordingly.

The plants I recommend as examples are those with which I have a significant amount of personal experience, or which were recommended by experts. The majority of these plants are either perennial or self-seeding, so you need plant them only once; they will naturalize in the garden. This is by no means a complete list; there is no such thing.

For best results grow as many different species as you can find, and don’t limit yourself to my (or anyone else’s) recommendations.

Assemble guilds with the plants you have rather than searching for the “right” plants to use. If you need something to fill a niche but can’t find a certain plant, try using another species in the same genus or family that may serve the same function.

A quick aside: I do not include cultivation instructions for any plants. This is because each site, and each microclimate within each site, is so variable that it is impossible to say just how to grow a certain plant. I assume you have some basic gardening skills; if you don’t, the resources section offers some excellent books to get you started.

Grow what interests you, and if it doesn’t thrive, either move it or change the microclimate. If it dies, there could be any number of causes and influences. Regardless, it’s worth trying to grow the plant again, or perhaps a similar one that fills the same niche. Some plants grow best in special climates, but most of the plants listed here are versatile and easy to establish and maintain. I have also excluded the most common annual edibles, such as cucumbers, lettuce, and tomatoes, assuming that most people will list these as primary crops. I encourage you to mix these familiar annuals with plants that are new to you and grow them all within a fully integrated, multifunctional garden. You may choose to maintain a small, strictly edible kitchen garden up close to the house for those times when you just want to grab a quick salad, but even small gardens grow better with support plants. That being said, let’s look at some of the functional roles plants in a polyculture might play.

Edibles. Food is the most common use of a primary crop, but most edibles also serve other functions, and you will find that there is much crossover among the categories here. Plants like to stack functions, and so should we. Most annual vegetables are easy enough to grow; also try perennial edibles such as fruits and berries. More examples: horseradish, rhubarb, pawpaw, kiwi, passion fruit, currants, figs, sea buckthorn, goumi, akebia, and asparagus pea. I have a keen interest in the ancient vegetable crops from the Andes, such as oca, yacon, mashua, canna, and ulluco. These plants come from the same places that gave us tomatoes, potatoes, and peppers, and most of them will do quite well in temperate climates, but they can be difficult to find. Still, it is important to diversify our gardens and diets as much as possible, as well as preserving the foods of other cultures, so it is usually worth the energy to track down unusual seeds and plants that interest you.

Medicinals and Aromatics. It is quite possible to grow and process all or most of our medicine with just a few carefully selected plants. We can grow remedies for colds, headaches, muscle pain, toothache, allergies, and stress, as well as fill our homes with wonderful incenses and potpourri. There are many excellent books on medicinal herbs, so here I will just name a few of my favorite ones, which no temperate garden should be without. These include spilanthes, garlic, echinacea, dandelion, ginkgo, hops, valerian, yarrow, jasmine, mullein, raspberry, and as many plants from the mint (Lamiaceae) family as you can find room for.

Ornamentals. There is no such thing as a plant that is strictly ornamental. Every plant, whether a magnolia, a gardenia, or Grandma’s favorite daphne, fills a function other than just being beautiful. It may, for instance, create shade, wildlife habitat, and forage opportunities. Still, don’t be afraid to choose to grow something simply because you think it is beautiful.

Some gardeners become obsessed with “practical” function and forget to include beauty and inspiration as essential components. Many edibles and medicinals are extraordinarily beautiful and make great front yard landscape plants; these include artichokes, hops, blueberries, akebia, and passion fruit. And don’t forget to include jasmine (aromatic), magnolia (soil builder/aromatic), rose (edible/medicinal), hawthorn (medicinal/habitat), and bamboo (fiber).

Fiber Plants. Fiber plants add functional diversity to the garden, as well as providing opportunities for moneymaking craft projects. Some fiber plants, such as bamboo, can provide stakes and trellis materials, while others are better for making baskets and sun hats. These include flax, nettle, willow, hazel, cattail, ivy, akebia, blackberry (said to be the very best by a basket-weaver friend), cedar, jute, hemp (illegal in some places but extraordinarily useful), kenaf, hops, vine maple, passionflower, and most tall grasses.

Nitrogen Fixers and Detoxifiers. Sometimes, such as in a cover crop, the purpose of the primary crop is to repair or improve the soil. An ecological garden should have a few areas in cover crops at all times to ensure that we give back what we take from the soil. You should also include in each garden guild at least one nitrogen fixer, such as beans, clover, or a tree legume like locust. You can plant guilds directly into a cover cropped area by just mulching or digging a small section and putting in the new plants, while leaving the rest of the area in cover crops. Mulches

In addition to annual cover crops there are many perennial plants that accumulate large amounts of leaf or root mass, which can then be harvested as mulch for neighboring plants. Include several of these in your overall garden design, but because they grow so big and so fast, give them plenty of room so they don’t overwhelm smaller plants.

Comfrey is my number one choice: It is easy to grow from just a small root cutting; it can be cut down several times a year for mulch or compost; and it will grow back within a few weeks. It is beautiful and medicinal and makes an excellent summer hedge. Also try elecampane, clover, burdock, mullein, artichokes, sunchokes, nettles, and plenty of deciduous trees (for the leaves).

Habitat Plants. Habitat plants provide shelter and forage for wildlife and are often best placed in the outer edges of a garden, where they can delay and nourish any hungry critters who might otherwise eat your primary crops. Good forage plants include clover, hawthorn, blackberries, and sunchokes. It is also a good idea to create habitat within the garden: places for songbirds to nest, and places for snakes and toads to hide before they come out to eat slugs at night.

In the interests of giving back to nature and nurturing species other than our own, I encourage you to include a healthy dose of habitat plants in your garden design. Start with native species, asking local experts what they recommend. Plant a few coniferous trees, which live and provide habitat for centuries. Overall, the more lush and diverse your garden grows, the more it will become a natural ecosystem of its own, with you, the gardener, as just one of the many living species within.

Insectaries. Many gardeners have an inclination to eliminate every insect from the garden. However, if we strive instead to encourage a healthy and diverse insect population, the insects will mediate one another, and the garden as a whole will benefit. Many plants attract or repel some sort of insect, which means you can choose which insects to encourage or discourage in your garden. There are several common plants, known as insectaries, that are known to be especially useful in this regard, and you should include at least two plants for this purpose in every garden bed.

The first type of insectary brings in ladybugs and predatory wasps that eat garden pests like aphids and cabbage moths. These include yarrow, dill, angelica, lovage, valerian, and most plants in the carrot (Apiaceae) and mint (Lamiaceae) families. Other plants, such as nasturtium, calendula, marigold, chives, and the entire onion family (Liliaceae), either act as traps for harmful insects or excrete substances that repel them.

A third category attracts pollinators like bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. These plants usually have big, colorful flowers and work especially well when planted next to fruit trees or vegetables that flower around the same time. For example, tulips and other bulbs, when planted in an orchard, will bloom at the same time as the fruit trees and attract insects that pollinate the blossoms.

Also, native pollinators such as hoverflies and mason bees like to visit dandelion, sweet pea, Oregon grape, camas, currants, and cinquefoil. Finally, always include the easy- to-grow pollinator favorite, phacelia. If you have issues with bugs or disease, add more compost or spray jauche, and be sure everything has enough—but not too much—water. Also, make sure you have plenty of air circulation in each garden bed.

The Eight-Layer Garden

Once you have assembled lists of the plants you want to grow together, you are ready to place each plant into the appropriate niche in space. To do this, think again of a forest. We can break down the spatial niches in a forest into eight basic layers: roots, ground covers, herbs and vegetables, shrubs, small trees, tall trees, vines, and water plants. By including all eight layers in our garden designs we make best use of available space and other resources and create a multidimensional, forestlike environment.

I will go through each of these layers briefly below, listing a few good examples to start with. Work through each layer on paper, keeping in mind the individual garden beds you will use, and add plants to fill niches as needed. Return to your plant list: Use it to make a chart for yourself like the one in the sidebar on page 121. Choose primary crops from each layer and support plants that fill the layers around. Using this formula, which layers function, form, and time together, will help you establish long lived garden guilds that mimic and harmonize with natural cycles.

Layer One: Roots

All plants exist in the root layer, but some are grown primarily for their fleshy, edible roots and tubers. Roots are rich in minerals, amino acids, enzymes, and carbohydrates. Many of the plants listed below, such as sunchokes, burdock, and chicory, also produce copious amounts of aboveground foliage and fill more than one layer. Some plants have shallow roots, while others penetrate twenty feet or more into the soil.

As a general rule, assume there is at least as much growth below the soil as you can see aboveground. Try to space your plantings so that roots don’t compete for elbow room but instead stack together as they grow down like the layers of branches and foliage above. My favorite root crops include beet, burdock, canna, chicory, daikon, garlic, groundnut, horseradish, oca, potato, rutabaga, turnip, sunchoke, sweet potato, and tulip.

Layer Two: Ground Covers

Ground covers provide a living mulch over soil that, if exposed, would dry out or cover itself with weeds. It is good to get ground covers established when the taller plants are still young and the sunlight still reaches the ground. Once established, most ground covers will spread readily and can be extended to other areas of the garden. Try planting a “napping lawn” of Corsican mint or white clover. Then stretch out on a summer day and enjoy the fragrant, cool leaves against your skin!

The plants listed here tend to be low-growing and will do well under- neath perennial herbs and shrubs or around patches of annual vegetables and the other layers of the garden. It is quite possible, and highly recommended, to establish a semipermanent ground cover over most of the perennial garden. Try cinquefoil, clover, Corsican mint, crocus, erba stella, gotu kola, kinnikinnick, nasturtium, oregano, prunella, purslane, spilanthes, strawberries, thyme, violas, violets, and winter squash.

Layer Three: Herbs and Vegetables

A large portion of our home remedies and summer annuals fit into this category. Many plants in this layer need partial to full sun, so design plenty of sunny edges around the garden to accommodate them.

Most herbs and a few vegetables are perennial and live twenty years or more, but most veggies are annual or biennial, taking up space in the garden for only a short time. This makes them an excellent choice for planting next to perennial plants that are still young. The annuals will shade the ground and provide food for you but will die by the time the perennial needs the space.

A polycultural garden should include many kinds of herbs and vegetables, such as alexanders’ greens, amaranth, arugula, beetberry, black-eyed Susan, calendula, cattail, chamomile, chives, cleome, columbine, comfrey, feverfew, good King Henry, jute, kale, lovage, marigold, milkweed, millet, Oregon grape, parsley, poppies, quinoa, sea kale, skirret, soybean, stevia, summer squash, sunflowers, tree collards, valerian, vervain, yarrow, and zinnias.

Layer Four: Shrubs

As with ground covers, establish shrubs when the trees are still young, because many of them need sun to get established. Once established, most shrubs will be relatively drought and shade tolerant and will help filter the wind through the low parts of the garden. This is important because though trees provide an excellent windbreak, if there are no shrubs, then the open space creates a cold wind tunnel, which can be rough on tender herbs and vegetables.

Trees and shrubs require less maintenance than annual vegetables, and some can produce hundreds of pound of food each year, with almost no labor once they get established. Most will benefit from regular mulching and pruning. Many of the fiber plants fall into this category, as do most of the small fruits. Try artemisia, artichoke, bamboo, blackberries, blueberries, ceanothus, chrysanthemum, currants, gardenia, goumi, honeysuckle, huckleberry, hydrangea, jujube, lavender, prinsepia, raspberries, rose, rosemary, salal, salvias, and wintergreen.

Layer Five: Small Trees

Here we find many of our large fruits, some nuts, and plants that supply countless other products, such as shade, mulch materials, wood, and wildlife habitat. Small tree crops are the heartbeat of permanent agriculture, and every garden should have at least one, if not several. Most small trees take several years to fruit but will usually outlive the gardener who planted them, providing food for many generations to come.

Start with apple, cherry, dogwood, elder, figs, hazel, hawthorn, pawpaw, pear, persimmon, plum, peach, sea buckthorn, strawberry tree, and willow. Be sure to get a “pollinizer,” or mate, for fruits that need it, such as kiwi, akebia, peaches, figs, and some kinds of cherries, apples, and plums.

Layer Six: Tall Trees

Tall trees are the slowest-growing and longest-living layer, with some species living up to five thousand years. Be sure to plan for their size at maturity; grow short lived herbs and vegetables in the space the trees will later fill. Tall trees provide wildlife habitat, lumber, erosion control, food, medicine, firewood, and windbreaks and create the essential canopy that helps shade and mulch the forest/garden floor. My favorites include chestnut, ginkgo, linden, magnolia, monkey puzzle tree, mulberry, oak, walnut, and yew.

Layer Seven: Vines

Vines add a junglelike feel to the garden and help maximize vertical space, which is especially good for cramped urban settings. The long stems can be used for basketry. If left untrellised, some vines will make a good ground cover. Or use the trellis to create a microclimate by placing it to reflect sun, block wind, or both. You can prune back vines every year or let them climb wild, toward the sun.

Most vines are shade tolerant but will flower and fruit toward the top, where they can reach the light. Vine brambles make great habitat for spiders and other beneficial insects. Many nitrogen fixing legumes are climbers, which makes them good choices for the vine layer. The list of beautiful, multifunctional plants for the vine layer includes akebia, bignonia gourds, Chinese yam, grape, hops, hyacinth bean, jasmine, kiwi, luffa, passion fruit, scarlet runner bean, schizandra, and sweet peas.

Layer function, form, and time together.

Layer Eight: Water Plants

Every garden should have at least a container pond, and if you choose to establish an ecological home water system, such as described in chapter 3, you will certainly need an assortment of water plants for your swales, ponds, and slime monster. These plants cleanse and aerate the water and provide shade, food, and habitat for fish, waterfowl, and humans. Try bacopa, duckweed, lotus, wasabi, watercress, water hyacinth, water iris, water lily, rushes, cattails, horsetail, canna, and some chrysanthemums. If you design each guild carefully, you will be able to include many different plants in every microclimate. Always keep in mind that the design of your system should be site-specific and make use of available resources. The plants and methods in this book, even if used exactly as described, will work on some sites and fail on others. Experiment with different ideas, techniques, and philosophies, then develop a system that works best for you.

Again, always be sure to give each plant plenty of elbow room. Clotted areas provide the moist, sticky conditions many harmful pests need to thrive, and when plants are too crowded they compete for nutrients, which weakens them and makes them vulnerable to insects and disease. So water, weed, mulch, and prune when necessary. The most common mistake gardeners make is planting things too close together— remember how big the plants will be at maturity, and make sure they have the space they need.

If you aren’t ready for a greenhouse, or if you just want to extend the season at multiple points, use cloches—little miniature greenhouses that cover your garden beds and protect plants from frost. You can build a simple cloche out of some sturdy wire mesh and a piece of clear plastic (actual greenhouse plastic is best). Just poke the mesh into the ground along the edges of your garden bed to make a hoop over the bed, lay the plastic over the top, and weight it down with some rocks. Or cut the bottom off a few gallon sized milk jugs and use them to cover individual plants. All types of greenhouses and cloches get good and hot inside, so water often.

Making Plants from Plants

As you develop your polycultural paradise garden, you will need to acquire and propagate a lot of plants. Set up a nursery area in a sheltered spot where you have daily access to water and use the tips below to multiply the plant material you bring home.

Almost every plant will grow from root divisions or stem cuttings and will make seeds from there. Look for cuttings throughout your neighborhood and in parks, nurseries, and botanical gardens. Most people will not mind or even notice a few snips here and there; some gardeners I know take a pair of clippers and a few envelopes wherever they go.

Here are a few tips for making plants from plants, using vegetative propagation:

Find or make a propagation box that is at least four inches deep. Mix up a rooting medium using nutritionally neutral substances such as perlite, vermiculite, or pumice. I like to mix all three. Some people just use sand or pea gravel. Experiment and see what works best for you. The medium should be light and fluffy. Don’t use compost, because the microorganisms will think the cuttings are food scraps and try to decompose them.

The purpose of the rooting medium is to facilitate air and water flow for the rootless cuttings and to make room for the new roots as they grow. It is usually not at all necessary to sterilize the rooting medium; you can even reuse it by just rinsing it out and spreading it in the sun for a few hours, then putting it back into the propagation box and starting again. If disease or rot persists, however, compost the old stuff and start fresh.

Mix up a batch of willow tea, which will help prevent rot and encourage quick sprouting. Gather some wild willow branches, chop them into two-inch sections, and stuff them into the bottom of a watering can. Keep the can full and use it to dip the cuttings in and water them as they grow. The willow cuttings in the watering can will also sprout, which is fine, but if the willow water starts to stink, make a fresh batch.

Take cuttings from plants that are dormant, usually more than two months before or after they flower. Once they have budded it is best to wait until after seeds mature to take cuttings. Avoid taking cuttings when the weather is very hot, as they will most likely wilt and die.

For stems, take cuttings that are three or four nodes long; remove the leaves from the bottom two nodes and trim the edges of the rest. Roots also have nodes, sometimes on tuberous chunks, in the form of eyes, and sometimes along the root itself, like little joints. Root divisions should also have three or four eyes or nodes. Most cuttings will keep in a moist paper towel or newspaper in the fridge for up to several weeks, but it is best to use them right away.

Make a hole in the rooting medium with something besides the cutting, such as a chopstick. This keeps the tender cutting from bruising on the way in. I stick the chopstick in, move the medium aside, then drop the little cutting in and gently tamp the hole closed. For root divisions bury the whole cutting (roots). For stems put the bottom two nodes below the soil surface and leave the trimmed leaves on top.

Always use a very sharp, clean knife or scissors for every stage of propagation. A little peroxide on a clean cloth works fine for wiping tools. Some people prefer alcohol, which is highly toxic to plants and should be well rinsed off before use.

Water the cuttings from below by placing the box in a reservoir of water, and mist occasionally from above with a spray bottle full of willow water. It is possible to make a humidity chamber using plastic and drip irrigation, but I don’t find it to be necessary for most plants. Keep the cuttings evenly moist until new roots form, then transplant carefully into sifted compost.

Equality Begins in the Garden

When I started working on this book I asked my mentor, Alan Kapuler, an expert organic grower, to name his top ten favorite plants. He said he didn’t have any favorites, so I told him to list the ten plants that no temperate garden should be without. He laughed and told me it was like asking him to name his favorite finger. He said, “All of them,” and then rattled off a list including crabgrass, barnyard millet, soybeans, and marijuana, indicating that the first two are essential to pull out and compost, while the last two are critical for health and nutrition.

He reminded me that, just as chemical poisons stall the natural cycles that build and maintain soil fertility, our own attachment to the idea that one plant is better than another stalls the creative cycle that builds and maintains fertility of thought and action. Again, the primary emphasis is on diversity. Use diverse strategies, experiment with diverse plant material, work with a diversity of people, and your projects, both in and out of the garden, will undoubtedly thrive.

By embracing diversity in our attitudes and in our gardens we can enhance the liveability, and longevity, of our communities and gain a deeper understanding of nature’s message: All beings are equal and interconnected. Through developing a love and reverence for plants and other living things we can create peaceful, functional ecosystems, and thus welcome ourselves home, to paradise.

To Prune or Not to Prune?

If you grow fruit trees or woody perennials, you will need to decide how to care for them. It is always a good idea to mulch around fruiting shrubs or trees to provide them with nutrients lost in the harvest. But what about pruning? As you consider how intensively you want to manage your landscape, it helps to consider death as integral to the cycle of life. When we try to grow our food as naturally as possible, we feel a certain relief that we are following the ways of nature rather than attempting to dominate or control it.

When a plant sheds limbs, leaves, flowers, and seeds, a life cycle perpetuates itself. We humans are simply a part of that process, and we can benefit from tuning in to the cycle as a whole rather than trying to make it work for our needs alone. So when you’re asking the question Should I prune my grapes? Try to see yourself as the willing servant to the garden, not the master.

Trees prune themselves in a variety of ways. If a tree is too dense, disease may kill a branch. If the fruit load is too heavy, a limb may break off. Fire, wind, and floods are also natural agents of pruning. Left to themselves, trees often regulate themselves better than we do. In fact, most fruit trees will grow and produce quite well if never pruned. Often, the need for pruning is the result of unskilled pruning in the past. Fukuoka experimented with letting older trees go wild and found that the more a tree has been pruned, the more likely it is that it will need pruning in the future.

The reasons to prune are as many and varied as types of trees. The most common ones are disease prevention, fruit production, creating access to fruit, tree size, and aesthetics. Pruning removes dead or dying branches and allows for better light and air penetration, which improves the health of the tree and the quality of the fruit.

Some trees, such as figs and cherries, simply do not need pruning, and unless you need to repair damage from a windstorm or a bad pruning job, you can let well enough alone. A simple rule of thumb is to let the tree dictate its own form. By working with the tree’s natural tendencies you can encourage a healthy, fruit bearing tree that requires less work and pruning in the long run. Here are some basic guidelines to help you prune as naturally as possible.

Pruning Tools

You will need hand clippers for the small stuff, loppers for branches up to half an inch in diameter, and a small curved saw for branches up to three inches; if you’ll be performing major surgery, a bow saw is helpful. I really don’t recommend chainsaw pruning, and while long handled or pole pruners can make it easier to reach those high branches, the novice pruner will always do a better job from close up. Get up in the tree and have a look!

Sharp tools are essential. Just like humans, trees heal much better when cut with sharp, clean blades. A sharpening stone should be included in your tool kit, and many people carry rubbing alcohol and a rag to wipe their blades between trees, preventing the spread of disease.

Timing

The most common time to prune is late winter/early spring. Spring pruning encourages growth, and fall pruning discourages growth. In the spring prune before the sap is running so that the tree does not waste energy growing branches that will just be cut off. Spring is the best time to work on the overall structure of the tree and encourage growth in desirable areas.This is the time for major surgery, while the tree has the entire growing season to recover. The tree will send its energy to the places where you made cuts to heal them, and often “suckers” will sprout from those points. This is why, if you go out to your apple tree in the spring and cut off all of the vertical suckers, you will just have to do the same thing next year.

Some results can be achieved only by pruning in the summer or fall.However, it is generally not a good idea to prune heavily just before a major frost, because the tree will not have a chance to recover in time to withstand the extreme cold. Late-summer or fall pruning allows the cuts to heal over before the strong push of spring and does not encourage suckering. This is a good time to remove those pesky suckers, and if you wait until after harvest, no fruit will be wasted. It is always a shame to cut off a branch that is loaded with little unripe fruits!

Making a Proper Cut

This is very important. It is possible to kill a tree with bad pruning, and the most common cause of this is a bad cut that becomes infected. For small branches, cut back either to the branch junction or to within one quarter inch of a dormant bud. The new shoot will grow in the direction the bud is facing. Larger branches are usually cut back to the branch junction.

Cut right up to, but not into, the branch collar, which is the raised ridge in the bark near where the branch comes out of the mother branch or tree trunk. Cell division occurs rapidly in this collar, sending out healing tissue to cover the wound. Do not cut off any portion of the branch collar, but don’t leave a big stub either. Try to find a balance.

Cuts should be clean. Tears in the bark of a tree are very vulnerable to infection, so it is often a good idea to make an undercut one-third of the way through the branch from below, then saw the rest of the way through the branch from above. If you do have a tear, try to clean it up by making a new cut.

Pruning Steps

1. Stand back and observe the tree as a whole. Repeat this step every three cuts to keep a perspective on the overall form. Yes, this means you may be climbing into and out of the tree several times during the pruning process.

2. Take out the “D’s,” in order: Dead, Dying, Diseased (moss and lichen are not disease, but fungus often is), Damaged, Dangerous (like limbs about to fall on the house), Doubling (two branches growing out of the same spot or rubbing on each other), and Deranged (bad angles, branches twisted around others). Stand back and look at the tree. If after removing the D’s you have cut around a third of the tree, you are done. Wait until next year to make any more corrective changes.

3. Choose your leaders, or main vertical structural branches. These will form the basic structure of the tree and can range in number from one to five. Choose vigorous, healthy branches that will support good horizontal branches. Allow ample space between the leaders and remove any other vertical branches. Stand back and look at the tree.

4. Choose your horizontals (branches growing from the trunk of the tree at an angle greater than forty-five degrees). These form the “scaffold” of the tree and will support most of the fruit. Choose healthy branches with good fruiting spurs. Choose branches that give an overall desired shape and allow easy harvesting. The lowest scaffold should be at least three feet above the ground, for good airflow. There should be one to five feet between each level of scaffolding. Stand back and look at the tree again.

5. Thin for air circulation. Remove any horizontal branches growing toward the center of the tree. Take out up to half of the vertical suckers, leaving the ones that fill gaps in the tree. Remember that these branches will eventually be weighted down with fruit and will fall into a horizontal position, so make sure there is room for them. Again, stand back and look.

6. Finally, prune twigs to encourage horizontal growth. You can often change the direction of a branch by pruning back to a bud that faces in the direction you prefer.

Remember, never cut off more than one-third of the tree in any one year. This includes the trunk, so choose your cuts carefully. It is generally better to make a few large cuts than many smaller cuts, to minimize the shock to the tree. Be patient and watch how the tree responds to your cuts throughout the year, so that you can make better decisions next time.

Eat the Weeds

In addition to pruning you will also most likely need to do some weeding. Sometimes this feels like playing God—deciding who lives and who dies is no small matter—and sometimes it feels like war. But weeds are not the enemy, and a warlike attitude will not help us toward a peaceful culture.

Take a moment to ponder the relationship of these plants to other living things around, now and in the future. Your weeds provide forage and habitat for insects, birds, and animals, as well as shelter for the seedlings of other plants. They cover the bare soil and bring moisture and soil life closer to the surface, where they can do their good work. Weeds should be respected for their tenacity, persistence, and versatility and looked upon more as volunteers than as invaders. Throughout its life every plant engages in a complex relationship with the ecosystem that produced it.

We humans can benefit greatly by participating in this cycle rather than trying to dominate it. We may indeed gain much wisdom by following nature’s tendencies.

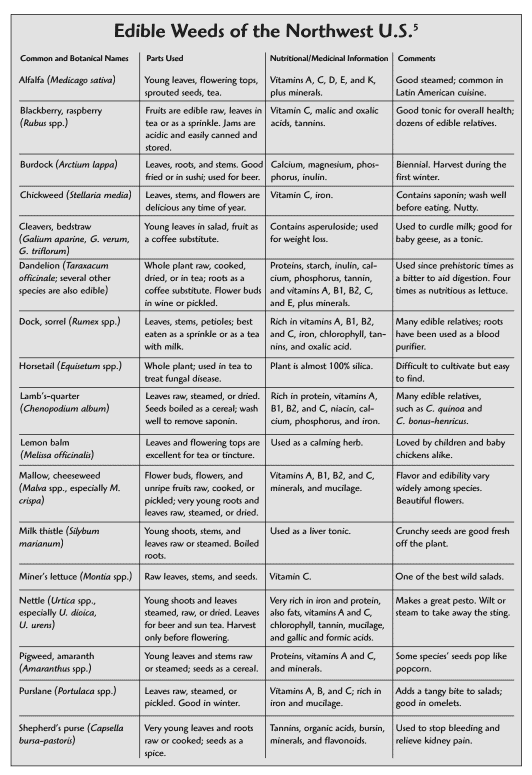

We saw in the preceding chapter that weeds can give us valuable information about our soil conditions. In addition, many common weeds are edible and/or medicinal. These wild foods are rich in vitamins and minerals and can be eaten raw or cooked or processed into tea or tincture and used as medicine. Some are delicious; others are bitter and eaten to aid digestion.

Most of the common vegetables we enjoy in our salads, such as lettuce, carrots, parsley, and mustard, were once considered weeds. Their wild kin are what we call weeds today, but why not let them act as volunteer herbs and vegetables and participate in the evolving polycultures? What better plants for a paradise garden than these hardy, self sown gifts from the soil?

On this, paradise gardener Joe Hollis writes, “We gardeners go on making the land say ‘beans’ (or ‘roses,’ or ‘lawn’) because that’s what we do, what gardening is. . . . But could gardening be more of a dialogue, the land getting to say what it wants to, too? It says such interesting things, all year long: shepherd’s purse, creasy greens, poppies, violets, lamb’s quarters—the way to hear their message is to ingest them.”(2)

Wild plants contain more nutrients than many cultivated varieties and can add new flavor to a tired out recipe. See the sidebar for a list of common edible weeds and their uses. Depending upon which part of the plant you use, you can prepare edible weeds in a number of ways. Often the sweetest parts are the new leaves, which can be steamed or eaten raw. Some roots, such as burdock and horseradish, are also good raw when peeled and grated.

If the plants are older, or tough or bitter, chop them up and dry them in a food dehydrator or on a drying rack like the one described in the next chapter. Mix in tastier herbs such as peppermint or fennel, and use the blend for tea. I like to make what I call Yum-Yum: Mix up stinging nettle, dandelion, and dock with your favorite culinary herbs, such as oregano, basil, parsley, and thyme. Toss in a few tablespoons of powdered sea salt and store the mixture in a jar with a tight-fitting lid. Sprinkle Yum-Yum in guacamole, salads, omelets, potatoes, tacos, pasta sauce, and more. This way you get all the nutrients in the wild plants without the bitter taste.

Some plants are deadly poisonous, so invest in a good book on wild edibles and be sure to correctly identify each species before you eat it. As with any new food, try just a little bit first, then wait a day or two to see whether you have an allergic reaction. Chances are, everything will be fine, but better safe than sorry!

Pull out poisonous plants and compost them in a nice hot pile for a few months. Compost neutralizes most poisons and toxins (except chlorine based chemicals), so a few poisonous plants won’t hurt anybody once they break down.

Invasion of the Garden Snatchers

So what about bindweed? What about kudzu? What about water hyacinth and butterfly bush, English ivy and quack grass? How are we supposed to grow wild, lush, diverse gardens, full of every kind of plant we can find, without some of them just taking over? From naturalists to conservationists to hobby gardeners and orchid thieves, the global debate over introducing, displacing, and cultivating tenacious nonnative plants rages on.Most “invasive” plants are pioneer species that thrive on disturbed soil. By trying to eradicate them with poisons and machines we disturb the soil even further and encourage more pioneer plants to come in and try to repair the damage.

Of course we should conserve pristine ecosystems, but with our constant disruption of natural ecosystems, through growth and industry, humans create conditions for invasive plants to thrive. Unless we change our actions and attitudes toward land use in general, waging war on “exotic” plants is just another futile diversion from the real issues.

Nature and the plants were moving slowly around the earth, replacing one another, interbreeding, and feeding insects, animals, and bacteria, for millennia before humans existed. Our own lives now depend on the varied functions they serve. It is perfectly natural for plants to succeed one another, and our national resources would be better spent preventing the real threats to the wild earth—namely industrial development, resource extraction, and industrial pollution.

In the United States and several other countries narrow attitudes about successful exotic plants have led to widespread and potentially catastrophic eradication plans. In February 1999 the National Invasive Species Council formed. In 2001 it released the National Management Plan, and as recently as 2003 it introduced several new weed control acts to the House and Senate mandating the control and removal of thousands of species of wild, edible, and medicinal plants across the nation.(3) California seedsman J. L. Hudson raised the alarm about a proposed “White List” several years ago. This White List, sometimes called the “clean list,” “comprehensive screening,” or “risk assessment,” would contain only the handful of species approved for existence on U.S. soil. The proposed list excludes more than 99 percent of the world’s fauna and flora, including many species native to North America, and does not allow for any new discoveries or introductions without a prohibitively expensive approval process.(4)

While it makes sense to want to protect native ecosystems, many of these new laws offer more benefit to herbicide companies than they do to nature. Not coincidentally, these chemical companies are behind much of the anti-weed legislation.However, if each community takes the thoughtful stewardship of its own watershed seriously, there is no need for wide sweeping government policy, and we can keep ourselves from the grips of the corporate profit mongers who push such unnecessary legislation under the guise of environmental stewardship. We can develop localized, nontoxic removal programs and can find uses for the masses of food and organic matter produced by these plants.

I am of the opinion that the most invasive species on this planet is Homo sapiens sapiens, which, along with the cockroach, housefly, and carpenter ant, has spread across nearly every bioregion in the world, leaving pollution, disease, and extinction in its wake. I would much rather see a rolling green landscape of edible buckthorn, Himalayan blackberries, and brilliant, blooming morning glory than the vast expanse of concrete and wafer board housing developments and homogeneous stands of genetically modified corn that threaten to cover the fertile earth today.

Nevertheless, please do think long and hard before introducing new species to a bioregion. If you’re living in it, it’s not a pristine ecosystem, but you probably don’t want to be responsible for clogging a major salmon run with imported water plants or wiping out a natural orchid population with aggressive, nonnative vines.Still, you also don’t want to accidentally eradicate a useful herb that thrives in your garden, so as a general rule never pull a plant you don’t recognize. Every pulled weed and every planted seed should be a result of prolonged, thoughtful planning based on careful observation and ecological ethics. This is especially important when working in or near wild or semi-wild places.

Generally, in urban or semi-urban environments the native ecosystem is covered with concrete, exotic ornamentals, and nonnative grass lawns. In this instance anything goes when it comes to plants. Grow as many different things as you can find; the better they survive, the better for everyone.

Discouraging Unwanted Plants

While I advise against totally eradicating any species from your garden, there will always be a few that try to take up more than their fair share of the space. There are several ways to remove these plants while still cultivating an attitude that embraces, rather than hates or fears, nature and diversity.

Try to see weeding as an act of mediation rather than expulsion, and embrace the notion that all species have equal rights to survival. Chances are, they are there for a reason. You may not be able to see this reason, but in the interests of biodiversity it is important to make at least a little bit of room for everyone.

Find out as much about the plant as you can. Ask yourself, What’s it called? Where’s it native? What are its uses? What conditions does it thrive in? Maybe there is a use for it that you didn’t know or think of before. If not, most weeds will go away if you cover them with a thick mulch or just yank them out and toss them in the compost.

If you pull something out and it keeps coming back, replace the plant with a species in the same niche that you prefer over the weed.

For example, if buttercup is taking over, try another spreader such as strawberries, cinquefoil, violets, or gotu kola. Most plants need certain nutrients to thrive, and if we plant a lot of something else that needs the same nutrient, it may outcompete the unwanted plant.

If that doesn’t work, try changing the microclimate. Make a shady spot into a sunny one or vice versa by trimming or planting some trees. Heat up the area by building a reflective, south facing wall. Amend the soil to change the pH level. Drain a moist area or flood a dry one. Chances are, your unwanted plant will not continue to thrive in totally different conditions.

Biodynamic gardeners collect the seeds of undesirables and burn them, then scatter the ashes around the garden. This seems to work well when done every year, perhaps due to cosmic messages, or just to the fact that you are collecting the seeds rather than letting them fall to the ground.

Sometimes plants that are weeds in one garden are absent in another, and you might be surprised at how easy it is to find people who want the plants and seeds that you don’t. It may be worth the effort to pot up some of those extra plants and take them to the next seed swap to give away.

Whatever level of weed management you choose, please never spray herbicides. They are carcinogenic to you and everyone else, run off through the soil to poison waterways, and radically upset the natural, successional abundance that your garden is attempting to provide.

Let’s not forget an essential piece of the ecological garden puzzle: the seeds. You need seeds to grow plants, and in many ways seed saving is the key to maintaining a biologically and economically diverse and thriving community. The next chapter will discuss the whys and hows of this ancient and essential tradition.

Notes for Chapter 5

1. Ed Ayres, “The Environment,” Utne Reader Online, www.utne.com/web_special/web_specials_archives/articles/1826-1.html, 18 November 2005.

2. Joe Hollis, “Eat the Weeds,” as found on www.webpages.charter.net/czar207196/eden.htm, October 2003.

3. National Invasive Species Council, www.invasivespecies.gov, November 2003.

4. J.L. Hudson, “Stop the White List,” www.jlhudsonseeds.net/WhiteList.htm, 18 November 2005.

5. Sources for edible weeds chart: François Couplan, The Encyclopedia of Edible Plants of North America (New Canaan, CT: Keats, 1998); and Ben Harris, Eat the Weeds (Barre, MA: Barre, 1968).