“Our goal is to naturalize ourselves in the environment. This will involve changing ourselves and changing the environment: convergence toward ‘fit.’ Perfect fit means the free and easy flowing of matter and energy between ourselves and our environment; life lived as a complete gift—from the garden to us, from us to the garden.”

—Joe Hollis(1)

“The sad reality is that we are in danger of perishing from our own stupidity and lack of personal responsibility to life. If we become extinct because of factors beyond our control, then we can at least die with pride in ourselves, but to create a mess in which we perish by our own inaction makes nonsense of our claim to consciousness and morality.”

—Bill Mollison(2)

Urban Ecology

Many people see ecological living as something they will do later, when they can finally afford a big place in the country, but I say, “Start now!” Even, or perhaps especially, if you live in a tiny apartment surrounded by a concrete jungle, you can usually find simple ways to repair the earth, educate others, and prevent further destruction of the natural world.

Growing ecological gardens, wherever you can, is never a waste of time. Nothing lasts forever, and if you can get a few baskets of food without damaging the environment, and perhaps leave behind some long living fruit trees, then the larger ecological community will surely benefit from your labors. If you can do these things while also educating others, then your work will succeed many times over.

Further, not everyone wants to live in the country, and if everyone moves there it will all become the city. Many people plan to spend their lives in the city, happily, and have no plans to go rural. This is good, because if we want to support the growing human population for more than another few centuries, we are going to have to grow up, not out.We also must ensure that urban communities can provide for their own needs, using resources from the local area. These needs include food, building materials, water, medicine, and much more, and currently there are no cities to provide a working model, though some cities, like Portand, Oregon, are starting to gain ground.

We can create local models by simultaneously caring for the earth, caring for the people, and recycling resources. In these models rural food surpluses will supplement urban subsistence gardens, and the ecological integrity of each bioregion will depend upon how well the city dwellers can provide for themselves.

Improving the ecological health of cities is crucial to achieving a healthy bioregional community, and if the ideas in this book inspire you, then begin doing these things now regardless of where you live or whether you rent or own your garden site. Do it for the land and to experience the personal transformation; consider the harvest a bonus, rather than the goal. The sooner and more fully we embrace an ecological ethic in our daily lives, the better our ability to place ourselves within the deep ecological context of our communities, and the clearer that context, the more possible our goal of sustainability.

Urban ecology is not so much a matter of “saving the earth” as it is a chance to improve the ecological viability of our own human lives and, thus, our chances of survival as a species on earth. The earth probably does not care whether we save her. She will most likely continue to turn and breed life long after humans have gone extinct. If we continue our current trend of wanton consumption and shameless waste, this will occur much sooner than later.

I know I sound like Chicken Little saying, “The sky is falling!” However, this deep impermanence, while it may seem like so much doom and gloom, is actually a blessing: Our own fragility gives us the impetus to act now to create healthy lives that harmonize with

nature, and to know the comfort, joy, and inspiration brought on by an organic life. Why waste years and decades locked into jobs and consumer boxes that kill and oppress us when paradise is the alternative?

In my experience most people want to eat healthy food, care for the earth, and do other things that help create a better future for humans and other species, but they feel powerless against economic and social constraints. This has a lot to do with the fact that millions of people don’t have a place to grow food, and the people who do have access to land, such as in rural and suburban areas, rarely steward it to the extent we need.

In addition to land, we also need tools, seeds, plants, and other materials, and most people can’t afford to just go out and buy it all. It is a common misconception that you need a lot of money to transform your home, garden, and community into paradise. But you can’t buy your way to a healthy ecology—you have to innovate it.

Integral to growing paradise gardens is recycling resources to do so. Every city in the world is rife with useful waste, and recycling it is an essential component of a healthy urban ecology. By understanding the flow of resources in the community around our gardens, we can better place those gardens within their deeper ecological and social context. Yes, growing organic food is always worth doing, but what of the truck loads of good organic produce that farmers and distributors throw away? This waste could be food on your table and compost in your garden.

Get acquainted with locally available, free resources—land, food, and otherwise. This is the first step in turning your yard into a garden and your neighborhood into a community, and recycling those resources is the next step. Focus on making best use of what is near you now, and buy new stuff only as the very last resort. The more we recycle the waste stream toward meeting our basic needs, the closer we come to closing the ecological loop.

Urban ecology is a big issue, and one that will take many years and many ideas to understand, but if we start with growing food where we can, we will be moving in the right direction. We can find space and resources that don’t cost money; we can build gardens and communities that make social and ecological sense.

This chapter will focus on making these resources more accessible. We will look at how to find a garden space if you don’t have one, and how to make the most out of the spaces you find. Then we will see how to tap into the flow of useful surplus that goes to waste every day, in every city in America, and how to divert that flow toward your garden and community.

Look Before You Leap

Before we can build ecological gardens and communities, we must first take the time to look deeply into our surroundings and try to see how best to integrate ourselves with the natural ecology. Humans are notorious for their inability and/or unwillingness to look at the natural signs around them, and this tendency is probably how we got in such deep water with the natural environment.

Sure, you might be all fired up to bust out some fabulous project, and I don’t want to discourage spontaneous creative action, but it is essential that we learn to look. Only through careful observation can we avoid making the same mistakes twice and determine what to do next.

During this observant, assessing phase, you should start a journal to keep track of what you find and to document the ideas and designs you come up with later on. Include garden maps and design ideas, seed harvests, lists of where you find good resources, contact information for fellow gardeners, drawings of your projects, and whatever else comes to mind. Such journals will become treasured community heirlooms, so choose a well-bound book with acid-free paper, and try not to leave it out in the rain!

Observation means more than just looking around with your eyes at what you see right now. There are many ways and many levels on which to see things, and I will describe a few important ones here. Before you read any more, take this book and go sit outside, where you have a decent panoramic view of your neighborhood. Now, as you read, look at your surroundings and try to see them in the ways I describe. Do this every morning for a few days.

This exercise might feel a bit contrived, but you really must do it, because it will help train your subconscious mind, and you will be surprised at how quickly your perception changes. Just as a dance step or a piano riff may seem difficult or impossible to do at first but can become easy, even automatic, over time, so can we train our minds to see and respond to nature. Ready?

Look Deep

This is a proverb familiar to hunters, who must learn to look deep into the woods for deer and other prey. Use your eyes and try to see as far into a landscape as possible. Look past the first layer of foliage, through the gap between trees, and past the tops of small plants.

One of the first times I went to the garden of my friends and mentors Alan, or “Mushroom,” and Linda Kapuler, we spent the afternoon wading through a dozen or so varieties of giant marigold plants in bloom. There must have been millions of flowers, and I had never seen marigolds that were different from the little pom-poms sold out in front of supermarkets.

Mushroom said, “Look at these flowers! Aren’t they beautiful?” I replied, “Oh, yes, so many different reds and oranges.” Then he said, “No, look.” And pointed at a single flower just inches from our faces.

I followed the line of his long finger into the center of the flower and saw, to my utter amazement, that it was one of a kind. All of the flowers were marigolds, and the ones in this patch had come from the seeds of a single flower, but each flower had a unique shape and color. By looking deep into the garden, then into the patch of marigolds, then into each flower, I was able to begin to understand what it means to be diverse.

Looking deep also means using all our senses. You should look with your eyes, but also listen, taste, touch, and smell your surroundings. Practice looking deep into a garden, into the woods, into a handful of soil, and at your community. Look in every direction: up, down, under, behind, around, through, and at different times of the day. Write down what you see. Deeper, use your spiritual sense—your intuition—and make note of what your instinct sees.

When developing ecological gardens and other community projects, we need to make observations on different levels. The two main ones are the macrocosm and the microcosm. Each includes important sublevels of observation, which I will elaborate on below. Look deep at each level to create a fractal-like sense of what you see. Look past the obvious, check your assumptions, and use all your senses.

Macrocosm

From seeing your garden in the context of your neighborhood to seeing yourself in the context of the universe, the macrocosm is the big picture. This includes the embedded energy in every tool and resource, such as how much pollution was caused by manufacturing and transporting the greenhouse plastic, or how much forest was destroyed for the lumber to build raised garden beds. When you use recycled materials you minimize embedded energies and help prevent pollution by intercepting waste, rather than creating waste through consumer demand.

Looking at the macrocosm means searching for patterns in space and time. Look at all the big things and see how they fit together to make the whole. Look for large scale patterns and relationships. Try to determine where they go and where they come from by following the connections from one observation to the next. In most cases these patterns will repeat themselves on each smaller scale, and through them we can find ways to make our small work resonate with the big picture.

Microcosm

Now tune in to the subtler details of what you see. Look deep into the macrocosm and pick out the microcosm that is your life, your garden. In the garden look deeper into each detail, from an individual tree to the smallest soil organism. Again, look for patterns and notice opportunities.

Within each microcosm there will also be many microclimates—special niches that yield special circumstances, which you can change or take advantage of. I’ll get into microclimates in a minute. For now focus on training your senses to see the details. Some garden designers believe you should observe a site for at least an entire year before making any changes. I recommend this when at all practical—you will save a lot of time correcting errors if you understand the natural flows before making any changes. Chances are, however, that you will want to start sooner. That’s fine; just start small and spiral outward and you won’t need to worry too much about making irrevocable mistakes.

Gaining Access to Land

Now that you know how to see, you’re ready to start looking for a garden site. The next few pages will address the problem of urban land access and look at ways to stretch the spaces you find. If you already have a site, then these tips will help you make it the most efficient space it can be.

What If You Don’t Have a Lawn?

For people who are lucky enough to have fertile soil in their own yard, starting a garden is easy. For those who don’t have good soil—or don’t have a yard at all—starting a garden takes a little more effort. Most soil, especially in urban areas, responds well to organic improvements, and it usually makes more sense to build soil on a convenient spot than to travel far from home to garden in an area that is already fertile.

We’ll learn how to build good soil on any ground in a later chapter, but what if you don’t have a garden space at all? In the next few pages we’ll look at how to find places to grow gardens, and how to make the most out of the spaces you find. The biggest limit to what you can do is your own creativity, so see what you can think of and share your ideas with others. Ultimately city dwellers’ best resource is neighbors, so tap into their hearts and minds, and don’t hesitate to share your own.

The following land access strategies will help you get started.

Use the Neighbor’s Lawn

It may seem odd in our modern American culture, but in other places around the world people frequently share yard and garden space with their neighbors. If you’ve been eyeing that nice sunny lawn next door, dreaming of filling it with fig trees and big red tomatoes, what could it hurt to ask?

Go on, go over there, bring some seeds and a smile, and ask! I have seen spectacular gardens come together when a group of neighbors with adjacent yards take down the fences between their lots and share the land communally. All the ideas in this book are most effective when done in community, with the people who live nearby.This doesn’t mean everyone can’t have their own space to do as they choose—only that the natural ecology is allowed to be more fully interconnected, without plants, insects, animals, and natural flows having to overcome fences and other human made obstructions.

Rent a Plot in a Community Garden

Many cities have some sort of community garden program. Ask at the local university, Agricultural Extension Service, or gardening store, or online—just type in the name of your city and “community garden.” Most of these programs lease ground from the city and rent out small plots to local gardeners on a seasonal basis. If you can’t find a program locally, would you like to start one? Chapter 9 has several ideas for community garden projects.

Volunteer at a Local Farm or Help Friends with Their Gardens

Most organic farms offer free produce to volunteers, and some will lease you a small plot of your own. This gives you an opportunity to learn from the farmer and access to the farm infrastructure, which includes important resources such as irrigation, seeds, surplus starts, et cetera. Some farms also hire seasonal workers, which can be a great opportunity to spend your summer learning, exercising, and eating fresh produce. If you can’t find a local farm to work with, volunteer to help your neighbors with their small garden. More options usually reveal themselves as new relationships mature, so build community through voluntary interaction and you won’t be without a garden for long.

Garden in Pots and Containers

Most annual vegetables are well suited for container gardening. Even a small patio can hold a few planters—get pots out of a garden center dumpster or use other recycled containers such as sinks, bathtubs, wine barrels, and plastic buckets with holes drilled in the bottom. Try strawberries, carrots, beets, tomatoes, cucumbers, zucchini, herbs, and salad greens. Try a self-contained potato garden: Take some chicken wire and make a round cage. Put a layer of thick straw in the bottom and toss some potatoes in. Cover with straw, leaves, or soil, water often, and keep adding more mulch on top as the shoots emerge. Soon you will have a basket full of fresh potatoes.

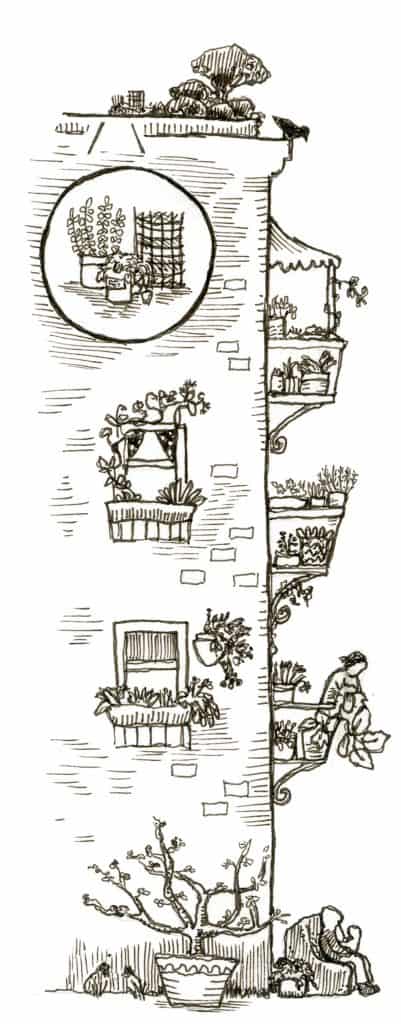

Use the Roof

If you lack patio or yard space but have a flat, accessible roof, consider building raised beds or planter boxes on the roof. There are fabulous rooftop gardens in big cities all over the world, with everything from small containers of herbs and salad greens to large planter boxes filled with trees and perennials. Get creative with the space you have now and better options will unfold later.

De-pave Your Sidewalk or Driveway

Rent a concrete cutter or just get together some friends with crowbars and rip out the pavement around your house. It doesn’t take that much work to convert a driveway or parking area into a garden. I have seen several wonderful examples, and the residents didn’t regret the lost pavement for a second. The broken up pieces—aptly called “urbanite”—work great as stepping stones or patio pavers or for building raised beds and terraces. Park on the street and enjoy the extra exercise while walking home through your new garden.

You may even want to tear down a whole building, such as a garage full of junk; recycle the junk and building materials, and grow plants instead. I would much rather have a living, edible garden next to my house than a dirty old box full of consumer crap. Think about it—you probably wouldn’t pave over an orchard to build a driveway, so why choose the pavement over the trees just because it’s there now?

Grow Food in the Existing Landscape

You don’t have to turn over a big area or even disrupt existing plantings to integrate some food plants. We once rode bikes around town with a big bag of zucchini seeds, planting them wherever we saw a gap in the landscaping. Later we saw big plants in some of the spots and harvested some delicious zucchini! I have also planted fruit trees into existing beds in front of local businesses or at the edge of a park.

This strategy works well, because the city or property owner maintains the landscape, and your plants get watered—sometimes even weeded and fertilized—right along with the plants that were already there! The downfall is that whoever is in charge of the site may notice your plant and pull it out or may spray it with toxins. Still, this is a good option for generating more food around town, and it can be great fun.

Also look for good spots in alleyways, along back fences. Often there is a garden on the other side of the fence, and you can plant small beds along the outside that benefit from the surplus water and fertility.

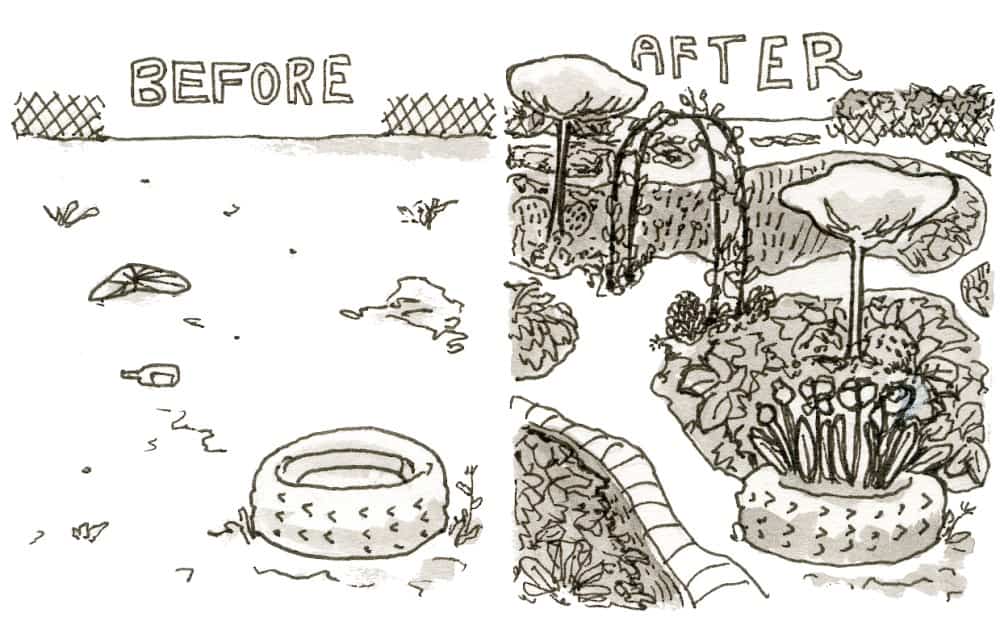

Start a Garden in a Vacant Lot

You can do this with or without permission. Sometimes property owners will let you plant vegetables and fruit trees in a sunny, under used corner. Others may say no if you ask but won’t notice for a long while if you just do it without telling them.

When the Food Not Lawns collective started our first garden, in an overgrown section of the park, the city didn’t know we were there for almost a year. We got the combination to the gate from a neighbor, cleared out all the trash and debris, and started gardening. By the time folks from the city came along to ask questions, we had a beautiful garden established, and they let us continue to use the space. They even sent park workers to drop off chip mulch once in a while!

There are countless examples like this, where people took over an area, grew food, and maintained access for many years. Some of these squatted gardens eventually gained ownership of the land. Sadly, there are just as many examples of gardens that were eventually bulldozed and paved over. In my opinion it is usually worth a try, and you will probably get at least a season’s reward for your audacity. This and the previous option are often called guerrilla gardening—see chapter 9 for more tips along these lines.

As you look for places to grow, ask yourself some important, practical questions: Will you actually go there to garden? Will you be inspired by the surrounding space? Will the plants have an opportunity to reach maturity? Will you want to eat the produce? Grow what you love, what you eat, and what you want to look at, in a space that makes you feel healthy and empowered.

Making the Most of a Space

Don’t let the idea of the perfect garden spot keep you from planting things right where you are now. Making the most of every space is one of the primary purposes of paradise gardening and ecological design. Here are some important pointers for maximizing the space you have available now.

Grow Up

Using vertical space wherever possible will double or even triple your yield, because for a tiny amount of ground space, you get lots of produce. Grow plants that climb, such as cherry tomatoes, cucumbers, gourds, and beans. Hang a salad garden near the kitchen door. Or grow plants up a trellis, rooted in large pots or small beds.

Try growing upside down tomatoes by planting a handful of seeds in a hanging bucket with a hole cut in the bottom. Water often and watch tomato vines grow out from all directions. Thin to the strongest few vines and harvest often.

Grow in the Shade

Many gardeners value only the sunny spots, but thousands of edible and beneficial plants thrive in partial to full shade. True summer veggies usually prefer full sun, but try spinach, kale, collards, raspberries, mints, beets, and most salad greens in an area you thought might be too shady. You may be pleasantly surprised.

Think Outside the Raised Bed

Filling big square areas with annual vegetables is but one of the many varied and wonderful ways to grow good organic food. Even a small corner can become a fruit bearing oasis filled with cherries, currants, grapes, or any number of perennial shrubs and trees.

Carve out odd shaped sections where a large bed won’t fit. Convert curvy strips around your lawn into garden beds, leaving wide grass paths in between. Or just plant little islands around the yard.

Also try mixing annual vegetables with existing landscape perennials. Plant long living fruits such as blueberries, plums, grapes, apples, and pears, and enjoy the bounty of your ingenuity for generations to come. Most garden fruits will bear within the first three years, depending on the variety and age of the tree when planted.

Make Use of Available Water and Fertility

In areas that are naturally soggy, such as near a dripping hose or by the roof drain, plant a garden filled with plants that will thrive on the moist soil. Along the same lines, if an area is naturally dry or the soil seems barren, find plants that prefer the dry soil or can improve it, rather than trying to force plants to grow in a soil to which they are not suited.

This principle also applies to soil fertility—if you have a rich area, use it to grow your most important plants, even if it doesn’t seem to be the most aesthetically or socially appropriate area. By this I mean do it in the front yard, y’all! Don’t underestimate the beauty of your food garden.

If well designed and tended with love, it will far surpass the beauty of any ornamental landscape, and your neighbors will prefer it to the static lawn that was there before.

Make Microclimates Work for You

Take plenty of time to carefully observe the site—sun, water, soil, traffic, and natural and industrial influences—and make a note of the apparent microclimates around your garden area. The term microclimate refers to the specific conditions of a particular site within a larger ecosystem. This could be your individual garden versus the local growing area, or a specific spot within that garden versus the whole site. Around even a small home or garden site there may be a dozen or more types of microclimates, each with a distinct set of conditions: hot and dry; cool and wet; sunny and moist; shady, dry, and acidic; and so forth.

There are a number of factors to consider when looking for and designing microclimates, including soil, wind, frost, heat, water, and of course function. First, look at the soil. Where is it dry, wet, warm, cool? Is it thriving with life or is there not a bug to be found? Next, notice how the wind moves through the garden; it can be very easy to filter and direct (more or less) wind through a site.

Cold wind often has a devastating effect on tender plants. Thus it is important to identify the less hardy zones in the garden and plan accordingly. Watch out for these little frost pockets, and look for opportunities to direct warm winds toward heat loving plants, to prevent cold wind tunnels from damaging tender plants, and to take advantage of (or avoid) wind’s drying effects.

For example, you can deflect a frost using a white, south facing wall and/or overhead cover. Many plants that are not otherwise hardy in a certain region will thrive up against a nice warm wall. Likewise, rock borders, brick paths, fences, trellises, and waterways can also catch, store, and reflect heat, divert or filter wind, and shelter tender plants.

Existing weeds provide useful clues about the soil and microclimate (see chapter 4 for more on this). Also, look at how the water moves through the garden, and look for opportunities within. Learn to recognize and note the special circumstances that any of the above elements impose on the site. Find several microclimates in your home and garden space, and try to identify their individual needs and opportunities.

Adjacent microclimates influence each other, especially along the edge. For example, a greenhouse not only is a warm, humid microclimate in itself but also creates varying microclimates on each side, below, and above. Thus you can create a warm microclimate along the south side of a greenhouse, using the space to grow heat loving plants. If you put a dwelling on the north side of the greenhouse, it will benefit from the surplus heat and protect the plants from chilly northern winds. Likewise, you can look for a natural microclimate, such as a shady grove of oak trees, and use it to grow useful shade plants that would not survive in the sun of the garden.

Some people recommend following your pets around to find microclimates. On a cold winter day put the cat out and see where she goes; chances are you will find a warm microclimate where you can plant a winter garden or put a sensitive houseplant. On a midsummer afternoon notice where the dog seeks shelter from the heat, and you may find a cool, dark place to dry herbs or store fresh foods.

Further, within each microclimate, and again within the whole, there will be a wide diversity of niches, some of them filled with living creatures and plants, others waiting for a symbiotic opportunist or two to settle in. By learning to identify the specialized opportunities within a site, you can assess its potential and determine what steps to take when building beds, improving soil, and choosing plants. Knowing your niches and microclimates will help you make best use of your space, increase the range of plants you can grow, and thus multiply your overall yield.

Identifying Resources

When looking for a garden space, also keep an eye out for the other resources you will need, such as plants, seeds, tools, and soil building materials. Start with the waste stream and work backward. Ask yourself: How can we use all of this trash to make our lives more beautiful, more ecological, more interesting, more fun, safer, healthier, and more peaceful? By making good use of what is going to waste around us, we can drastically reduce the effort and expense required to start and maintain a garden. Dumpsters across the country are brimming with valuable resources, from organic food to old growth lumber. Before you decide where, how, and how big to grow a garden, tap into the waste resources around you and develop a clear vision of what you really need. You will save time and money, plus interrupt the waste stream, which prevents pollution down the line.

It is important to learn to differentiate between useful surplus and true waste. That pile of old Styrofoam might seem like it would make good insulation but in reality may just disintegrate all over the garden— leave it at the dump where it belongs. Conversely, organic materials such as food scraps and dimensional lumber should always be diverted from the landfill and at least used for compost and firewood.

Don’t overlook the people around you as a valuable resource. Ask your peers and neighbors for their opinions and ideas. They know, have, and do things that can benefit the community as a whole. Connect with them and share your ideas. See chapter 10 for more about how to connect with like minded people in your community and beyond.

Free Plants and Seeds

In order to establish diverse paradise gardens, you will need as many different plants as you can find. This can be an expensive habit, especially if you buy starts at retail prices. Even small veggie starts can run a few dollars each, and perennials and trees can cost twenty dollars or more. This is a last resort for most of the gardeners I know—we prefer to start most of our plants from seeds or cuttings, salvaging the rest from the waste stream.

Seed samples aren’t expensive when you consider that each sample, at about three dollars, usually contains at least a hundred seeds. It is important to support small scale seed companies, but if you are really broke, most of them will give you last year’s stock for free or at a big discount, especially if your garden project is geared toward community benefit. When stored correctly, seeds can last hundreds of years, so these outdated packets are a real score.

Seedlings can take a long time to grow, however, and often it makes more sense to bring in larger, more established plants. You can propagate these yourself with cuttings gleaned from local areas. You can also find a wide diversity of plants going to waste all around you; with a little nurturing these will thrive and flourish in your garden.

It is quite possible to grow a large, diverse garden without paying a single dollar for plant material, by getting donations, salvaging composted plants, and connecting with local garden clubs and seed exchanges, all of which I will elaborate on below. Before you know it you’ll have your own surplus of plants to give away or sell to raise money for your projects.

Donations

Most places that sell plants end up with heaps of unsold merchandise every fall. You can connect with these businesses and secure donations for your projects. Also solicit donations from local gardeners, landscapers, and farmers. Many of them will have surplus and are happy to share. Post flyers and Internet ads describing your project and mentioning that you need plants and seeds. This is especially effective if you can get a local nonprofit to sponsor you, so that donors can benefit from the tax write-off.

Just as it is important to respect the earth, it is also important to respect the sources of our donations. This means always being courteous to workers, respectful to paying customers, and honest about where the donations are going. Food Not Bombs once lost a valuable organic bread source because some new volunteers went in for the weekly pickup and were rude to the bakery employees. Another time a volunteer was caught shoplifting at a health food store, and we lost twenty-five pounds of organic food a week for several months until we could repair the relationship with the store. Avoid wasteful behaviors like these and your work will be that much more effective.

Salvage

For a variety of reasons, some places would rather throw extra plants away than donate them. It is easy enough to get these out of the dumpster after hours. Cruise the back alley behind local garden centers and see what you can find. Also visit local farms and ask if you can pick through their compost for starts. I have seen truckloads of tomato plants thrown away because the farmer deemed them unfit for market, but they would have been fine for home gardening.

Find and visit the local organic waste dump. Most cities have at least one place where landscapers and anyone else can bring truckloads of yard debris and dump it. If you don’t know where it is, call the folks at a landscape company and ask them where they take their debris. You can also invite those landscapers to dump debris at your place (see chapter 4 for more on this).

These piles are rich in useful resources. Besides mulch and compost materials, you can often find caches of living plants. A friend of mine once came home from the dump with a pickup truck full of chrysanthemums and lilies—about two thousand dollars’ worth of living, beneficial perennials! Just as one person’s junk is another’s treasure, so can one gardener’s weeds be another’s flowers.

Garden Clubs and Seed Exchanges

The other gardeners in your neighborhood are one of your most valuable resources. By connecting with them you can gain access to the wisdom of the ages, and through seed and plant exchanges you can exponentially increase the diversity of your garden and your bioregion. Look for flyers at local nurseries, or do an Internet search to find out about local garden clubs and seed exchanges. You may never have to pay for seeds and plants again!

Before you are ready for plants and seeds, though, you will need to build garden beds, establish paths, and accumulate necessary tools such as shovels, digging forks, buckets, wheelbarrows, tarps, and more. Let’s examine some strategies for finding the other materials you need to turn your yard into a garden.

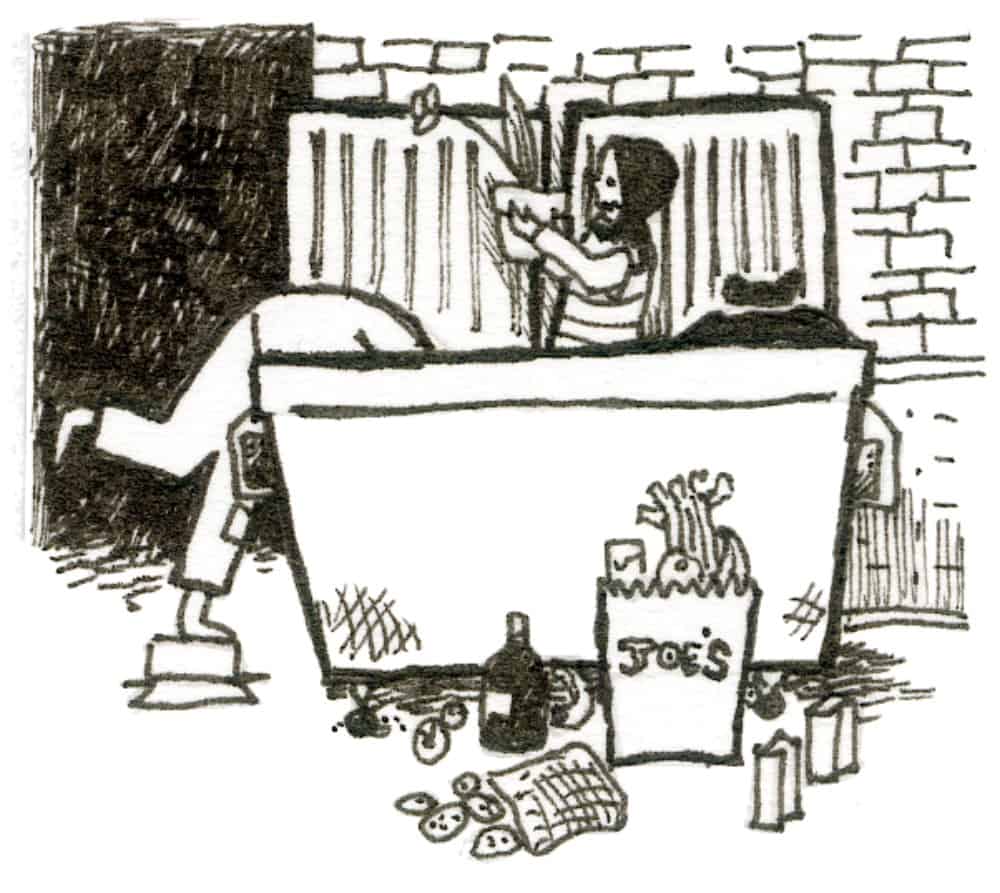

Tapping the Flow

When I was about ten years old my dad had some pet rabbits in the backyard of his suburban house in Long Beach, California. We couldn’t afford commercial rabbit food, so once a week, Dad took my sister and me around to the dumpsters behind the local supermarkets. He would jump into the dumpster and toss out lettuce, carrots, potatoes, apples, and an assortment of other fruits and veggies. We girls would cringe in the alley, putting the vegetables into a box and hoping none of our friends saw us.

Later, when cooking for Food Not Bombs, I realized that much of that “rabbit food” of my youth was served at our own table as well as given to the rabbits. Further, many of our other possessions, such as the furniture, my first computer, and many of Dad’s tools, also came out of local dumpsters. I hadn’t realized it at the time, but my father was an accomplished urban scavenger, putting the Greater Los Angeles waste stream to good use for his family and friends.

As a child I was embarrassed or disgusted to eat food out of the trash, but now I am proud to be a trash digger. Dumpsters are an under tapped but rich, diverse source of free food, from fifty-pound bags of bread to delicacies such as organic almond butter and chocolate truffles. Sometimes if a single jar breaks, people will throw out the whole case. Other products have expired sell-by dates but in fact are good for several days or weeks after.

And it doesn’t stop with food. The waste stream is also rife with nice clothing, furniture, electronics, and expensive building materials such as oak boards and power tools. Sometimes the best finds are not immediately recognizable as useful resources. For example, a pile of pallets might not look like your new bathhouse, but many pallets are made of good hardwood lumber and can be disassembled, de-nailed, and reused to make beautiful, sturdy buildings.

Cardboard makes great mulch or insulation; an old speaker head can be turned upside down and used as a magnetic holder for hand tools; metal scrap can become fencing; old fabric can be made into rag rugs or patched together to make a quilt or curtains; broken bikes can be parted out and pieced together anew; inedible food scraps can be taken home in buckets and used for compost or sheet mulch. Be creative and make note of where the good spots are, so you can revisit them later.

You can get excellent free resources out of the trash in all kinds of places, from urban business districts and residential neighborhoods to rural farmsteads and wild places.

Here are some places to start.

Business Districts

The city is tremendously rich in waste resources. Every dumpster, every house, every alley has something interesting, something useful, something worth finding. People in cities all over the world cherish these found items, make art with them, make tools, and live better through their resourcefulness.

Look for alleys behind stores, restaurants, factories, and distribution centers. This is where the big dumpsters live, and useful merchandise goes right in with the trash. Bring gloves and a flashlight, park on the street, and walk down the alley to the dumpster. You may have to climb in and open up bags to get at the good stuff, so be careful and clean up your mess, or you might find the same dumpsters locked next time.

Look behind places that sell food, including restaurants, stores, and warehouses. You will find edible food and good stuff like buckets and pallets. For other items, think of where you might go to buy them, then see if you can get them from those places, or from where they got them, for free. Free items might be cosmetically challenged or somehow defective, but they could still work just as well for your purposes as the same things at retail value.

If you are looking for a particular item, such as carpet for sheet mulch or canvas tarps, let your fingers do the walking: Look in the phone book or online for local merchants, and check behind the stores after hours. The same places will often be willing to donate surplus materials to a community project—it usually doesn’t hurt to ask.

Sometimes you will discover a regular source of food or supplies; we frequent a well known salsa dumpster and regularly get good organic bread and condiments from another place. In circumstances like these, it is essential to be respectful of the facility.

Chances are, you are not the only person who frequents that spot, so don’t ruin it by making it a nuisance for the associated business by leaving a mess, making a lot of noise, or harassing the employees.

Residential Neighborhoods

Cruise residential streets the night before trash day, or go post-sale scavenging after a sunny weekend. On Friday or Saturday morning check out the newspaper, drive around, and make a list of yard sales. Then drive by on Sunday night, after the sale is over, and look for piles of stuff put out for the trash or with a sign that says FREE.

The best time of the year for residential trash digging is after the winter holiday consumer frenzy, when people are cleaning out the old as they integrate their new possessions. This is especially effective in upscale neighborhoods, where people are more likely throw stuff away than to donate it. In college towns we celebrate “Hippie Christmas” in mid-June when college students move out and go home, leaving piles of furniture, clothes, books, computers, and more in the dumpsters behind their apartment buildings.

Residential neighborhoods are also a great source of plant material. You can usually harvest a few seeds or take some cuttings without any problem, especially if the parent plant is hanging over a back fence or other out-of-the-way site. Of course, it rarely hurts to ask, so introduce yourself to that neighbor with the fabulous jasmine and get some cuttings for your garden!

Urban Gleaning

Sometimes what you need isn’t in the trash at all but is hanging from the trees above. A single plum tree can yield hundreds of pounds, and most urban fruit trees drop more on the ground than the property owner can deal with. Look for plums, cherries, apples, figs, and more in your neighborhood, and see if you can have some of the fruit.

Besides trees, most cities also host a plethora of edible and medicinal plants, from blackberries down by the river to wild echinacea in a vacant lot. Develop a map of these local resources and harvest what you need. However, some urban sites can be very toxic, so use your powers of observation to make the good choices.

Gleaning Rural Surplus and Farm Junk

Gleaning usually refers to getting free food from the leftover harvest at local farms. Many counties have gleaning programs in place, or you can just call around to local farms and ask whether they have any surplus. This is but one of many ways to make good use of the resources going to waste in the countryside near you.

Often you can also glean some useful junk. Don’t be afraid to ask about that pile of cedar boards or that cool old bathtub out by the barn. Most rural homesteads have piles of great stuff that has been lying around the place for years, and the owners are often happy to let you haul it away for little or no money, or in exchange for a few hours of weeding time.

Rural Wildcrafting

Let’s not overlook the vast and wonderful diversity of food, medicine, and other resources in the wild and semi-wild places outside town. The forest, the ocean, the desert: All these environments are rich in materials that can help build closed-loop systems in town.

Wildcrafting is a useful skill that can bring wonderful mushrooms, edible fruits, and medicinal herbs to the table. Native seeds can also be found in the wild, then cultivated and perpetuated at home to be used for restoration and regeneration later on. The shore brings even more good stuff: seaweed, driftwood, oyster shells—all this and more can be harvested and used to enhance your compost, mulch, and garden beds.

However, it is very important that taking from these places be a last resort, when you absolutely need something and cannot find it or a good replacement through other means. There is precious little left of our natural resources, and we would do well to carefully safeguard them. Never take more than a little from any natural site; your impact should be invisible. It is best to engage in the proper training with a local naturalist before taking anything at all. You will learn much about the local ecology and help ensure that your impact is a positive one.

Cyber Scavenging

Another way to find and distribute free stuff is through the Internet. Almost everyone has heard of eBay—an excellent way to sell unwanted items to the highest bidder. There are also many sites that cater to people giving stuff away for free. Yahoo! has an assortment of “freecycle” lists for cities around the world. Also check out craigslist.org, tribe.net, myspace.com, and the like for good local connections. (2020 LOL to this from the 2006 text!!)

The Free Box

A free box can be a cardboard box in front of the house, put out for a few days until the stuff is gone, or an established space in the community to which people take their surplus and look for what they need.

If your neighborhood doesn’t have a free box, build one in an unused side yard or the local park.

Build a big wooden box, big enough to hold larger items but not so large that you can’t reach to the bottom.

Drill holes in the bottom for drainage, in case something spills or rain gets in, and if you want to get fancy put a simple roof over the box. Post a sign that says FREE BOX and make a note asking people not to leave trash or toxic waste such as motor oil.

People will gather at the free box, giddy over the plethora of good free stuff, and will bring their surplus clothes, furniture, plants, and other items there rather than throwing them out or giving them to a thrift store. Relationships will begin, and resources will flow.

I recommend having a volunteer “free-box monitor”—someone who stops by once every couple of weeks, pulls out the trash and recycling, and takes stuff that no one has claimed to a thrift store or shelter. This role usually falls, by default, to the house that hosts the free box, but it is better when rotated among neighbors, to keep one person or household from burning out.

Alternatively, ask the folks at the local dump if they will host a space that can become a free store. I have seen several of these in city dumps, and they work well at keeping functional goods such as clothes, furniture, and building materials out of the landfill and in use.

Filling the Gaps

If you can’t get what you need for free, you still have several good options besides buying retail, such as barter, borrowing, and buying at a discount. Many small businesses and individuals are open to bartering; you can trade for labor, materials, crafts, or anything else of value to the person you are bartering with. Look for local directories of alternative resources such as natural health care, used building materials, organic food, home services, and so forth, and make contact with the individuals who have what you need.

If you need a certain tool for a specific purpose, often the best idea is to borrow it from someone. Some communities have tool libraries where people pool their resources and share them around the neighborhood. See chapter 9 for more on organizing resource exchanges and lending libraries.

The last thing you want is to waste any of that hard earned money, and even if you absolutely must buy something new, with all of the discount resources available these days, it is foolish to pay retail for most items. Before you buy anything look again at what you need it for, and consider whether you might just do without it. If you really must have it, then try to find it secondhand.

Thrift stores resell used goods at a discount, making them available to people who can’t afford them new or who would prefer to recycle. Many stores operate social services with the proceeds. Also, if you have a lot of large stuff that you need to get rid of right away, most thrift stores will pick it up from your house and even give you a tax receipt.Still, it makes more sense to distribute goods directly to the people who need them rather than through a third party that will charge money for them, so do consider taking your surplus goods to a local free box instead.

Yard sales are another option. They are also an excellent way to get rid of stuff and make a little money—sometimes a lot of money. I had a yard sale in which I sold surplus furniture, clothes, plants, kitchen supplies, and an assortment of other items that were not necessary to my home system. I made seven hundred dollars, enough to pay my rent for three months. I gained more space at home, distributed goods to community members in need at a fair price, and also gained an opportunity to take some time off work and focus on my volunteer projects.

Closing the Loop

As you establish and maintain a paradise garden, you will probably be surprised at the overwhelming abundance generated by your efforts. If you do not distribute or recycle these surpluses, they will become pollution and degrade the ecological integrity of your project. Conversely, if you give them away, you increase the yield and efficiency of your own system while simultaneously building community and preventing or reducing waste and pollution. There are few better ways to inspire the neighbors than by giving them fresh organic fruits or extra seeds and other resources.

Getting and giving away stuff for free is the root of a gift economy— one in which surplus resources, rather than going to the landfill, flow among community members in a collective effort toward a better life for everyone. A gift economy helps enable us to withdraw from the consumer paradigm and exist on our own terms while providing for our own needs. So give away your surplus and you will simultaneously build community, improve the natural environment, and make room for new ideas.

This also applies to garden space. If you already have a garden space but live in an area where many of your neighbors do not, consider sharing space with someone. Many people have enough energy and plenty of excellent ideas but do not have access to land or a space on which to grow. If you don’t have extra land but do have an indoor space such as a garage or workshop, why not offer it up to a community group for workshops and events? If you do not want to organize something yourself, perhaps others would like to host events at your space.

Small activist groups may want to host a benefit show or an event to raise money for their project, but without the capital to rent a space they’re unable to do so. A bookseller in Eugene lets people hold events like this at her bookstore in the evenings while it’s closed. If the event is free, the space is free; if there’s a door charge, she charges a nominal percentage. It works out for her because it brings in new customers, and it works for the community because it gives them a place to have dance classes, meetings, and workshops, as well as to gather and share information.

Now that you have a good idea of how and where to look for garden space, how to make the most out of that space, and where to find the supplies you need without spending a lot of money, you are ready to start developing your paradise garden. The next few chapters will move through some of the elements of a paradise garden, including water, soil, plants, and seeds, and will give you plenty of project ideas.

If I have my way, you’ll read this whole book before you actually do anything in the garden. If we are to build gardens and communities that will endure, we must first learn to weigh our options and assemble resources into the appropriate ecological design, rather than hastily throwing together projects that will do more harm than good to the natural environment. So read through, make notes, and develop a cohesive, ecological plan.

Notes for Chapter 2

1. Joe Hollis, “Paradise Gardening,” in Peter Lamborn Wilson and Bill Weinberg, Avant Gardening: Ecological Struggle in the City & the World (Seattle, WA: Autonomedia, 1999), 162.

2. Bill Mollison, Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual (Australia: Tagari Publications, 1988), 1.