“Humans still live in prehistory; indeed, all things still stand before the creation of the world. . . . The real Genesis is not in the beginning, but at the end, when society and human existence become radical. When we engage our roots—the history of human as worker, creator, molder—and have grounded our possessions in a genuine democracy without alienation, then there will appear in the world something glimpsed in childhood, a place where nobody has yet been: Home.” –Ernst Bloch, (1)

“I teach self-reliance, the world’s most subversive practice. I teach people how to grow their own food, which is shockingly subversive. Yes, it’s seditious. But it’s peaceful sedition.” –Bill Mollison(2)

This is not just another gardening book. Several parts of it are about gardening, but in the context of a garden that’s deeply rooted in a complex community ecosystem. This book is about how to be healthier and more self-reliant, and thus improve the ecological integrity of the community you live in, through growing diverse organic gardens and sharing the surplus.

The natural world is in deep decline due to the grossly unsustainable habits of humankind. This is no secret. You can find evidence everywhere, from global warming to rain forest destruction to mass extinctions, all of it done in the name of free enterprise and short term profit. Fortunately more and more people are waking up to these facts and working to find solutions on all scales. Let’s just hope it is not too late.

I do not know a magic word that will make a wasteful society into an ecologically healthy one, or even just turn a lawn into a garden—these things take time, practice, and dedication. But I do know some powerful strategies that, in my experience, make these goals more attainable, and I have done my best to bring them together here in this book.

How It Seems to Me

The eldest of four in an addicted, abusive, and estranged family, I had little access to alternative education or informed choices. Though born in Oregon, I grew up in the slums of suburban Los Angeles in the 1980s, where I didn’t learn much about self-reliance, natural living, or ecological harmony. Not that growing up in suburban Cleveland, rural Arizona, or New York City would have been much different. There are few places in America, or the world for that matter, that provide working examples of environmental responsibility in action.

For the first twenty years of my life I never thought about where my food came from; nor did I question the deeper workings of the food system or society as a whole. Though marginalized by my half-Mexican blood and low-income status, in many ways I was just like any other kid in the suburbs: I struggled to fit in, I fought with my parents, and I ate sugar and industrial meat almost every day.

Public school taught me to obey authority, and that words are more important than actions. Television taught me to buy my way to happiness, and that I should starve myself and keep my opinions to myself so I could find a husband and make babies. My family taught me to tolerate abuse in the name of love, and the mainstream workforce taught me that my time isn’t worth a living wage.

Ironically, none of these lessons seemed to benefit me in any real way—on the contrary, these lies I had been indoctrinated with seemed to lead only to a doomed and heartless culture. I realized this but didn’t know how to do anything about it, and at twenty-one I was clinically depressed over my lack of place or purpose.

I was lucky enough to have a few friends who encouraged me to question the mainstream values I felt so oppressed by, and to reach out for more information. I spent my last fifty bucks on a bus ticket from LA to San Francisco and quickly found work there, canvassing for Greenpeace. I had no experience with fundraising or environmental activism, but the other canvassers welcomed me, and I discovered the world outside the working class consumer box I’d grown up in.

I soon found that I could unlearn the bad habits of my upbringing and renew myself as an ecological being, and I began to try to live in concert with the other species around me. I became a vegetarian; I started recycling and riding bikes. I lost interest in shopping and watching television and started reading poetry, playing guitar, and paying attention to local, national, and international environmental issues. I learned that the planet is a mess because of human impact, and I resolved to do something about it.

Still, fundraising for a bureaucratic organization in a big city wasn’t exactly the Earth mother connection I was looking for. I quit Greenpeace and went to northern California to help defend the last of the ancient redwoods. For the next three years I worked with a wide variety of groups, doing actions and demonstrations in support of forest conservation, social justice, and food security.

In 1998 I settled in Eugene, Oregon, and opened a communal household that would soon become the hub of a large activist community. The people I worked with were well educated and extremely well informed, and now I began to develop a deeper analysis of how best to channel my energy. As a full-time activist, I was inspired to make changes in the world and in my own life. I dove into the work, passionate about my newfound power and eager to learn as much as I could about building community and living more ecologically.

Still, much of the work was about stopping something—logging, mining, violence, et cetera—and not much seemed to focus on starting real alternatives. One exception was a group called Food Not Bombs. Most activists are cash poor, having devoted their lives to volunteer work, and Food Not Bombs helps meet the need for good vegetarian meals.

Not that you have to be an activist to eat with Food Not Bombs. In hundreds of cities worldwide, local FNB chapters cook and serve free vegetarian meals to the public, using donated ingredients that would have otherwise gone into the trash. Through cooking with Food Not Bombs and interacting with the people we fed, I learned that it is not just activists who are concerned about the issues. Everyone is.

Everyone wants to live peacefully, take care of the earth, and be good to one another. Sadly, people feel disempowered by the system and are struggling just to survive. They don’t feel they have the time or the ability to change their own lives, let alone the whole culture.

Yet the more we ate together and shared ideas, the stronger we became. I was relieved to find something to do that created alternatives instead of focusing on problems. I was actively seeking and implementing positive, meaningful solutions, and by turning waste into food I was simultaneously reducing pollution, increasing my own quality of life, and building community.

Food Not Bombs offers free vegetarian meals in over a hundred cities around the world

Going Organic

As I learned more about agriculture and food in relation to health, the environment, and social justice, I quickly developed a deep commitment to eating an all-organic diet. And while it seemed expensive and difficult at first, the rewards were obvious: Within a few months I noticed a huge difference in how I felt—my energy levels were more stable, I wasn’t getting sick as often, and my complexion looked better than it had since before puberty. Within a year the manic depression that had plagued me for a decade was gone, and I was physically and mentally healthier than ever.

It is a proven fact that organic food is fresher and more nutritious than conventional food, and better nutrition translates into better health for humans and the environment. Many people prefer organic food because they say it tastes better, and a number of studies have attested to its superior nutritional quality. On average organic food contains higher levels of vitamin C and essential minerals such as calcium, magnesium, iron, and chromium, as well as cancer fighting antioxidants.(3) In addition, it doesn’t contain food additives, which can cause health problems such as heart disease, osteoporosis, migraines, and hyperactivity.(4)

Organic farming prohibits the use of polluting, carcinogenic chemicals, replacing them with tried-and-true methods such as composting, mulching, cover cropping, traditional plant breeding, and the use of carefully planned designs and crop rotations to build healthy soil and balance essential nutrients. Organic farmers reject genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and their livestock is free of drugs and hormones. Organic practices can also support wildlife health and habitat, and they produce less waste and pollution, including carcinogens and global warming gases.

However, the term organic has lately been co-opted by the federal government and corporate profit mongers, and I feel it is important to note that even “certified organic” farms often engage in harmful practices such as covering the ground with black plastic or using excessive fossil fuels, whereas many small, ecologically sound farms choose not to certify themselves organic for a number of reasons.

I encourage you to look at where your food comes from with a critical eye and choose according to your own ethical beliefs. Certification, after all, may be merely a piece of paper acquired by paying fees and jumping through bureaucratic hoops. Real ecological integrity in agriculture comes only through personal accountability, and what better way to learn about gardening than to go to where food is grown and ask questions? Support the local farmers and gardeners you trust, and build that trust by getting to know them. I guarantee that your body, your gardens, and your bioregion will mutually benefit from the extra effort.

From this point on I will assume that you agree that eating organic food and supporting ecological agriculture is better for your health and that of the planet than chemical agriculture and the industrial food system. My purpose in this book is not to convince anyone of these facts, but to make it easier for those of us who choose an organic lifestyle to apply these ethics to our diets, our gardens, our homes, and our communities.

If you need more convincing about the toxicity of industrial agriculture, see the sidebar below or refer to the resources section at the back of this book. Now on with the story . . .

Food Not Lawns

As my personal health and eating habits improved I became convinced that food—the source of our energy and, often, the root of consumerism—was also at the core of personal and community empowerment. It is extremely difficult to build an organic life on an empty stomach. When we are well nourished with good local food, we can work hard, get along, and build beautiful, ecological communities.

Healthy food is a basic right for everyone, but geographic, social, and economic boundaries often limit or deny access, both to food itself and to the land needed to grow it. Most people I talk to want to eat healthy, organic food and live in harmony with the earth and one another, yet they don’t know how turn these ecological ethics into a real, daily lifestyle.

Often the primary problem is not supply but distribution. Through cooking with Food Not Bombs, I learned that in every city in North America, truckloads of nutritious food go to waste every day. Much of this food is organic, and diverting the flow into the mouths of community minded people is like sending water into a dry garden: It makes everything grow and bloom.Further, food is only one of the deep diversity of resources found in the waste stream—and recycling the waste stream is the key to long term urban sustainability. Beyond food, shelter, clothing, building materials, plants, seeds, tools, and of course many acres of fertile soil sit idle in every town in America.

As I began to realize this, I continued to cook and serve free meals in the park but changed my focus from providing resources to teaching others how to find them on their own. The old adage still rings true: Give a person a fish and feed her for a day; teach her to fish and feed her for a lifetime.

It was with this in mind that a few of us founded Food Not Lawns, a grassroots gardening project geared toward using waste resources to grow organic gardens and encouraging others to share their space, surplus, and ideas toward the betterment of the whole community. Why Food Not Lawns? Most obviously, the name was a natural evolution from Food Not Bombs.(10) But more importantly, we called ourselves Food Not Lawns because the more we learned about food, agriculture, and land use, the more the lawns around suburban Eugene began to reek of gross waste and mindless affluence.

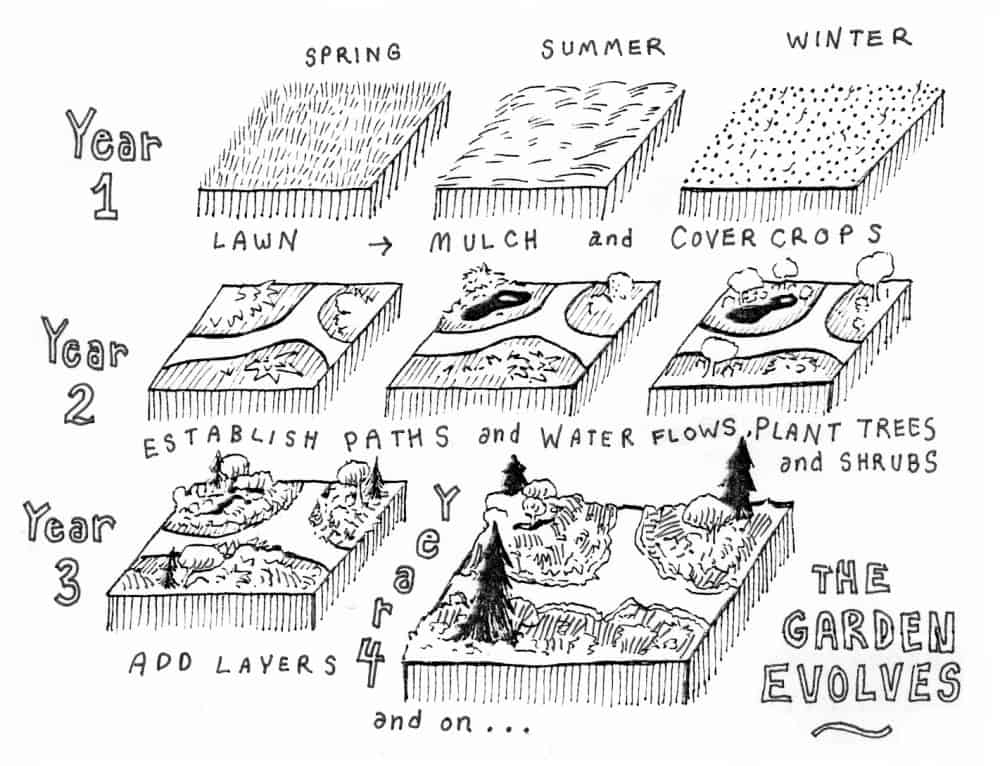

While looking for a garden site, we asked our landlord to let us grow a garden in the grassy front yard of our rented house. He refused, saying he wanted to keep the lawn intact, and while I tried to see his point, to me it was absurd. In a world where so many lack access to basic needs such as food and shelter, and where a lawn of a thousand square feet could grow more than a hundred edible and beneficial plant species, becoming a lush perennial “food forest” within three years, mowed grass seems an arrogant and negligent indulgence.

We did eventually find a nice spot in an abandoned section of a local park, where we grew a diverse organic garden. We ate some of what we grew and gave the rest away. We grew starts and seeds and gave them away, and we hosted workshops in the garden space. The produce nourished us, the starts and seeds inspired gardens around the neighborhood, and the workshops helped spread the knowledge gained from our experience.

The garden flourished, and other activists in the neighborhood became intrigued. All summer long people dropped by with plants, seeds, or tools to donate, or to volunteer for an hour or three, chatting and sharing ideas within our peaceful oasis. It was so easy and so much fun, and the positive effects were exponentially obvious as the neighborhood got greener and the people got more educated about organic food and urban sustainability. Our neighbors and their gardens bloomed with an abundance of food, goodwill, and inspiration.

Food Not Lawns started several more gardens and circulated seeds, plants, and information. We planted food all over town—vegetables and fruit trees in public parks, berries along the bike path, squash down by the river—anywhere that looked like it would get water and sunshine. Over the next several years we organized dozens of events, including seed swaps, farm tours, resource exchanges, and workshops on a wide range of topics, such as natural building, composting, organic orchard care, self-education, and community organizing. In the spring of 2000 I helped put on a weeklong community gardening festival during which a small affinity group planted a vegetable garden in a vacant lot around the corner from our house. Several months later, just before the juicy tomatoes and giant zucchini were ready to harvest, the landowner sold the lot to a developer who wanted to build an apartment complex.

The locals protested, saying there was ample vacant housing in Eugene (true). One neighbor locked himself to the bulldozer, with a sign saying SQUASH THE STATE! to prevent the garden from being destroyed, but he was arrested and the apartments were built. We lost that garden, but the event spurred a new flow of local and national interest, and ten more gardens popped up in other places around town.

Local and national media caught on, and we gave several interviews about sharing land and resources to promote peace and sustainability. Soon e-mails and letters flowed in encouraging our work, asking for more information, and telling of new chapters of Food Not Lawns in

Genetically Modified Foods

The last few years have seen an overwhelming flood of genetically modified foods into stores and kitchens around the world. In fact, since 1999 genetically modified organisms (GMOs) have constituted more than 70 percent of the corn and soy crops grown annually in the United States.

GMOs can cause insects and plants to mutate, rendering them either exceedingly weak or super-resistant to even the most toxic controls. Either way spells disaster for long term agricultural viability. Long term effects on humans and animals are still largely unknown but could, and most likely will, include similar results in the form of cancer, plague, gross overpopulation, or worse.

The top fifteen companies that make, patent, and serve up genetically modified foods are listed below. In general, chances are that if you’re eating nonorganic corn, corn syrup, potatoes, soy, or dairy, you are ingesting GMOs on a daily basis.

In a recent talk about the threats behind GMOs, consumer advocate Ralph Nader said, “Genetic engineering of food and other products has far outrun the science that must be its first governing discipline. Therein lies the peril, the risk, and the foolhardiness . . . without commensurate advances in ecology, nutrition-disease dynamics, and molecular genetics, the wanton release of genetically engineered products is tantamount to flying blind.

The infant science of ecology is under equipped to predict the complex interactions between engineered organisms and extant ones. As for any nutritional effects, our knowledge is also deeply inadequate. Finally, our crude ability to alter the molecular genetics of organisms far outstrips our capacity to predict the consequences of these alterations.”(5)

The companies that make, patent, and sell these life forms reject any responsibility for the irrevocable changes they cause to the natural environment. In fact, Monsanto’s director of communications has said, “Monsanto should not have to vouchsafe the safety of biotech food. Our interest is in selling as much of it as possible. Assuring its safety is the FDA’s job.”(6)

This is like saying that a car company doesn’t have to make sure its cars are safe, but the Department of Transportation should take responsibility for any accidents that occur because of equipment failure or bad design. The solution is obvious: If the suppliers of our food cannot be responsible for the safety of that food, then we need to take that responsibility into our own hands.

By refusing to consume GMOs, and by supporting organics instead, we send the message that we want food that is grown responsibly and with the best interests of all species in mind. Read the list below and stop eating the foods these companies produce. Call or fax them and tell them you don’t want GMOs in your food. Support local, national, and international movements to ban genetically engineered foods.

THE FRANKENFOODS 15

Campbell Soup

Coca-Cola

Frito-Lay

General Mills

Heinz

Hershey’s

Kellogg’s

Kraft/Nabisco

McDonald’s

Nestlé

Procter & Gamble

Quaker Oats

Safeway

Shaw’s

Starbucks

This list comes from a flyer by the Organic Consumers Association.(7)

The consumer waste stream is overflowing with valuable resources.

Washington, California, Pennsylvania, and Montreal. We soon connected with a global community of like minded people—activists, some, but mostly a diversity of working class people: healers, midwives, single moms, artists, musicians, lawyers, teachers, librarians, and plenty of organic farmers and gardeners. Apparently organic gardening with the larger goal of community sustainability appeals to people across many cultural and economic boundaries and unites activists, apathists, and many in between.

My own political views changed profoundly as the gardens taught me their lessons. I had lived and worked in a radical, anarchist/activist community for years and was inspired by finding a beautiful, positive way to manifest these philosophies. Notions of violent revolution dimmed next to visions of multicolored paradise and peaceful abundance. Dreams of industrial collapse became prayers for communities feeding and healing themselves.

Paradise Gardening

While reading up on similar projects in other towns I came across a book titled Avant Gardening, an anthology of stories and insights about community gardening, organic living, and urban sustainability. An article by Joe Hollis was of particular interest. In this he wrote:

Our world is being destroyed, in the final analysis, by an extremely misguided notion of what constitutes a successful human life.Materialism is running rampant and will consume everything, because its hunger will never be sated by its consumption. Human life has become a cancer on the planet, gobbling up all the flows of matter and energy, poisoning with our waste. What can stop this monster? Nothing. Just this: walk away from it. It is time, indeed time is running out, to abandon the entire edifice of civilization/the State/the Economy and walk (don’t run!) to a better place: home, to Paradise.(13)

I found these words to be so real, so poignant, that I went with a friend to visit Joe at his place in the hills outside Asheville, North Carolina. It was spectacular. Everything still glistened with morning dew, though we arrived well after noon. The humid Appalachian forest steamed with the aromas of moss and worms, humus and biodiversity. Flowering vines spiraled up the banister as we climbed to the house.

We met Joe and chatted for a while, and he encouraged us to explore the garden. He motioned the way we had come, and I realized that the dense forest we had walked through on the way to his door was actually a diverse, multilayered garden, packed full of fruit trees, annual and perennial edibles, medicinal herbs, and more.

Joe calls his approach “Paradise Gardening” and recommends that, instead of continuing to occupy niches in society, we return to our ecological niche: intentionally, as stewards of the earth. This attitude makes so much sense to me, as a gardener and as a human being, that I decided to use the word paradise to describe the type of gardening I write about. I will explain how to create such a garden, and I’ll use the term throughout to refer to the holistic attitude and natural gardening approach described in this book.

Ecology and Community

Growing paradise gardens and giving away the surplus makes communities better in the most fundamental ways:

First, we regain control of the quality and availability of our food supply, which results in healthier, more confident people. Next, when we share the harvest, our neighbors become more like family. This reduces waste from all directions.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, organic gardening reconnects us to the earth and allows us to place ourselves within the context of the larger ecological whole. This realization inspires us to live as if the earth mattered and encourages us to take responsibility for ourselves and our families.

Becoming a paradise gardener means cultivating an attitude of equality with all species and embracing a role as willing participant, rather than master and commander, of the garden and surrounding ecology.

This egalitarian attitude shapes our actions and approaches and defines the types of strategies we use to develop our homes, gardens, and communities.

Ecological living is not so much about understanding nature as it is about understanding ourselves. We must learn how to provide for our own needs without degrading our natural surroundings. This is primarily a social transformation, because humans are doing most of the damage. Humans are a part of the larger ecological community, and it is our blatant disregard of this fact that has gotten us into so much trouble.

Living ecologically means changing our whole way of being with the rest of nature, and gardening provides the setting for this transformation. If each of us grows even a small organic garden and shares the surplus, we will see a distinct cultural shift toward healthier people and stronger communities, not just through a direct increase in available food and information but also, and more importantly, through the way these actions change how people think.

In the garden, by stepping outside economic and social constructs for a moment to envision ourselves in the cradle of nature, we can get to know the ecological self. Through this eco-self we can place ourselves in the context of the ecological community in which we live, learn how to cooperate with natural systems, and eliminate or decrease the disharmony caused by our current unbalanced state.

The more we can understand ourselves in relation to the natural world we depend upon, the closer we will come to integrating into a healthy, ecological whole. More simply, by rejecting the consumer culture and instead embracing an outdoor life that is rich in organic foods, personal interactions, and intentional learning, we can live in a lusher, more natural alternative: paradise.

Wasted On Grass

French aristocrats popularized the idea of the green, grassy lawn in the eighteenth century when they planted the agricultural fields around their estates to grass to send the message that they had more land than they needed and could therefore afford to waste some. Meanwhile French peasants starved for lack of available farmland, and the resulting frustration might well have had something to do with the French Revolution in 1789.(11)

Today fifty-eight million Americans spend approximately thirty billion dollars every year to maintain more than twenty-three million acres of lawn. That’s an average of over a third of an acre and $517 each.

The same sized plot of land could still have a small lawn for recreation and produce all the vegetables needed to feed a family of six. The lawns in the United States consume around 270 billion gallons of water a week—enough to water eighty-one million acres of organic vegetables, all summer long.

Lawns use ten times as many chemicals per acre as industrial farmland. These pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides run off into our groundwater and evaporate into our air, causing widespread pollution and global warming, and greatly increasing our risk of cancer, heart disease, and birth defects. In addition, the pollution emitted from a power mower in just one hour is equal to the amount from a car being driven 350 miles.

In fact, lawns use more equipment, labor, fuel, and agricultural toxins than industrial farming, making lawns the largest agricultural sector in the United States. But it’s not just the residential lawns that are wasted on grass.

There are around seven hundred thousand athletic grounds and 14,500 golf courses in the United States, many of which used to be fertile, productive farmland that was lost to developers when the local markets bottomed out.(12)

Turf is big business, to the tune of around forty-five billion dollars a year. The University of Georgia has seven turf researchers studying genetics, soil science, plant pathology, nutrient uptake, and insect management. They issue undergraduate degrees in turf.

The turf industry is responsible for a large sector of the biotech (GMO) industry, and much of the genetic modification that is happening in laboratories across the nation is in the name of an eternally green, slow growing, moss free lawn.

These huge numbers are somewhat overwhelming, if not completely incomprehensible, but they make the point that lawns not only are a highly inefficient use of space, water, and money but also are seriously contributing to the rapid degradation of our natural environment.

I have traveled in the United States, Canada, Europe, Mexico, and South America, and most of the people I’ve met will agree that eating organic food is a good idea, as are recycling, conserving wilderness areas, and otherwise taking care of the earth.Nevertheless, as a society we continue to degrade our lands and cultures with pollution, mining, logging, a toxic and devastating agriculture, and a string of other abuses. We display our rejection of ecological responsibility through an irreverent consumer culture rife with waste and injustice, and we demonstrate our affluent denial by growing miles upon miles of homogeneous green lawns.

If we truly feel committed to treating the earth and one another with equality and respect, the first place to show it is by how we treat the land we live on. It is time to grow food, not lawns!

The reasons include reducing pollution, improving the quality of your diet, increasing local food security, and beautifying your surroundings, as well as building community and improving your mental and physical health. You will save money and enhance your connection with the earth and with your family.

Whatever happens, you may still choose to keep a small lawn for playing croquet and sunning with the chickens. Good for you! The term Food Not Lawns is meant as a challenge to the notion of a homogeneous culture; it is not a call for the eradication of all green grassy places.

A small lawn, incorporated into a whole-system design, helps provide unity and invites participation in the landscape. Lawns offer a luxurious and comfortable place to read, stretch, or exercise. If you are the kind of person who uses a space like this, you should have one somewhere near your house.

And why not enhance the lawn with edible flowers, fruits, vegetables, or other useful plants?

Or what about turning your whole yard into an organic food garden and using a local park, school, or natural area for recreation?

If we can change our land use philosophy from one of ownership and control to one of sharing and cooperation, we can renew our connection with the earth and one another and thus benefit through increased physical and mental health, an improved natural environment, and stronger local communities.

What have you got to lose besides a few blades of grass?

In cities around the world Food Not Lawns collectives work to set the stage for these transformations. We share a vision of freeing ourselves from a toxic, artificial culture and reuniting with our natural ecology through community interaction and paradise gardening.

But it is not flowers and strawberries the whole time. While we build gardens and educate ourselves, our governments wage war around the globe, and the corporations wage war on the environment. Even in our little neighborhood people can’t seem to get along well enough to take care of a local park, let alone save the world. For every seed that we save, every garden we start, whole ecosystems go down.

So while paradise gardens provide food, sanctuary, and many lessons about the earth, these lessons won’t endure unless we also apply them to the rest of the community—and to every other aspect of our lives.

Beyond the Garden

Paradise gardens are at the heart of a healthy urban ecology, and the next few chapters will provide many practical examples of healthy ways to make your garden grow. However, your own garden becomes a hundred times more bountiful when placed in the context of the larger community, and the rest of the book is about how to bring what you learn from the garden into your daily life, and how to build community through sharing food, resources, and ideas.

Many people today are talking and learning about ecological, economic, and social sustainability, each of which has varying definitions, depending upon whom you talk to. Unfortunately most models of one type of sustainability tend to inhibit the sustainability of another, such as when a logging project creates jobs but destroys the forest.

Overall, the whole of modern culture is not sustainable on any of these fronts. The current world population will double in just a few years, and again a few years later. Nothing can sustain such exponential growth in a finite area, and unless we begin to redesign the whole, starting with local communities and spiraling outward, we are, frankly, doomed. We must learn how to balance economic need with ecological priority and, perhaps most important, how to get along with one another while we’re at it.

The extent to which the global situation is ecologically and economically unsustainable is well documented elsewhere, so I will spare you the grim details. In short, the last threads in the web of life are fraying rapidly in the shadow of global development and scientific progress, and our survival as a species will be utterly dependent on our ability to change. It is time to think beyond our own gardens and put our ecological ethics into action throughout the rest of our lives as well.

Environmentalism and ecological living are often terms associated with activists, but you don’t have to be an activist to want to live as if nature mattered, or to want to change your community. As I said before, most of the people I meet do want these things but don’t know how to manifest them.

The first step is to start making choices that balance autonomous thought with integrated ecology. To create a sustainable future we must focus on exponential learning rather than exponential growth, and on accumulated wisdom rather than accumulated wealth.

By insisting that human communities not only provide for their own needs but actually contribute to and improve the natural environment, we can work toward a thriving human ecology that might have a chance at perpetuity. In short, when we work with nature, rather than against it, everything gets easier, more delicious, and potentially more sustainable.

This attitude, while sadly foreign to our fast paced consumer culture, works quite well in the garden, and it can work in the rest of the community too. The garden is an excellent place to start, but we must go beyond it to find the path to whole system ecological health.

Free your lawn!

Permaculture and Ecological Design

Around the globe, as people wake up to nature, ecological living, and ethical land stewardship, they are devoting themselves to building communities that are environmentally, economically, and socially balanced. In the past thirty years the ecological design movement has proven itself as an excellent resource for strategies and techniques that help communities realize this vision.

In 1979 Bill Mollison coined the term permaculture to describe his methodology for the “conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystems which have the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems.”(14) Since then many more great minds have contributed their own insights and experiences to the global movement of ecological gardeners and designers who call themselves the permaculture community. Today there are thousands of working demonstrations around the globe, all organized by people who have jobs, families, busy lives, and often minimal funding.

Permaculture designers use a succinct set of principles and techniques to establish homesteads and communities that provide for their own needs, require minimal care, and produce and distribute surplus food and goods. These principles and techniques merge well with the paradise gardening approach, and a paradise garden fits perfectly into the heart of any permaculture design. Like paradise gardening, permaculture emphasizes relaxation, sharing, and working with nature rather than against it. Meeting our own needs without exploiting others is the primary goal.

Further, the principles that make permaculture so successful in the garden also apply to other endeavors, such as home design, community events, and interpersonal relationships. These include activities like food preserving, natural building, environmental repair, ecological education, resource recycling, and using renewable energies including solar and wind power.

Permaculture stems from a triad of ecological ethics: First, care for the earth, because the earth sustains our lives. Second, care for the people, because we are people, and because people are the primary cause of damage to the earth. Third, recycle all resources toward the first two ethics, because surplus means pollution and renewal means survival. By allowing these three primary ethics to provide a foundation for our garden, design, and community work, we can move toward our goals of a peaceful culture and a healthy human ecology.

This transformation has exponential effects on the land and the people and has the potential to spark a global culture of peaceful, responsible communities. Maddy Harland, editor of Permaculture Magazine, says it well:

“Contact with the soil reminds us that we are an integral part of nature, rather than feeling shut out and excluded. The simple acts of growing and eating our own food, recreating habitats in which nature’s diversity thrives, and taking steps to live more simply are practical ways of living which connect us to an awareness of Nature’s seamless whole. Permaculture is a spiritual reconnection as well as an ecological strategy.”(15)

The Permaculture Ethics

Permaculture is not just about the elements of a system; it is also about the flows and connections among those elements. You can have solar power, an organic garden, an electric car, and a straw bale house and still not live in a permaculture. A project becomes a permaculture only when special attention is paid to the relationships between each element, among the functions of those elements, and among the people who work within the system.

Through a design process like permaculture, we can organize these relationships for optimum success. Our creativity is our most powerful tool for overcoming the ills of our culture, and design helps us harness that creativity and put it to work.

Yet, while the word “permaculture” does refer to a few specific techniques, most of what permaculture teaches is not new information. It stems from the wisdom of the ancients, blended with science and critical thought, and distilled into design formulas for modern use.I sometimes hear people say, “Permaculture is just common sense!

Yes, many of the techniques seem like common sense, but they are not common practice—yet. Why not? Perhaps it is because people do not know where to begin. The goal of this book is to help you create that starting point and, further, to develop a long term implementation plan that will help you manifest your thriving gardens and communities.

I will always adhere to the ecological ethics I learned through permaculture and devote my work to caring for the earth, caring for the people, and recycling resources toward those ends. I believe that these ethics will lead us down the path to an abundant human ecology, with plenty of yummy things to eat along the way. However, while I would never abandon the permaculture movement as a whole, I caution against allowing this or any other catchphrase to replace a working human ecology.

Don’t get me wrong: I love permaculture. I love to geek out on design theory and play with the principles and to study the techniques and try to apply them to my life, my home, and my garden. I love Bill Mollison for his silly jokes, his codgerish reputation, and his brilliant writing. I have studied permaculture and have met many amazing, inspired, and capable people who self-identified as “permaculturists.”

I have also, however, studied several other topics, such as biodynamics, kinship gardening, direct action, dance, music, and visual arts. All of these play as strong a role in this book as permaculture, and to call this a “permaculture book” would be to diminish both my own hard work and that of my dedicated mentors in these other areas. In truth, I am uncomfortable with the word “permaculture” and with the assumption that we as a species are entitled to permanence on this earth. My purpose here is not to alienate anyone, but to integrate a broader and, in my opinion, more inclusive perspective into the eco-organic-permaculture-sustainability mindshed.

This is obviously a conversation that needs to continue far beyond these pages, but for now I will summarize by saying that when I take action toward caring for the earth, and toward designing my life in concert with my ecological community, it feels right. Some call it permaculture, some call it common sense, some might even call it enlightenment. Personally, I do not seek enlightenment or exaltation, only the occasional bellyful of homegrown peaches and a chance to interact with the growing global community of like minded people. I always welcome comments, critiques, constructive criticism, and, of course, sweet little envelopes full of organic seed! So let us engage as a community of individuals who think our own thoughts, do our own work, and yet trust and rely upon each other as we move toward a common and fruitful future.

Radical As a Radish

Is this just the latest grasp at Utopia, another random idea from the radical fringe? At first glance it may seem so, but Utopia is a rigidly controlled world with no problems, no conflict, and no fear.

We must rather embrace the reality that, as humans, we will grapple with these and many other difficult issues.

The scope and quality of our survival is largely dependent upon how we deal with the inevitable and sometimes horrible facets of humanity. Therefore, while Utopia prescribes an authoritarian and impersonal recipe for perfection, this book insists that small, localized communities develop and support their own unique systems. In this type of flexible, individualized approach lies our true power.

My own work stems from a deep dedication to an autonomous, egalitarian attitude that some might associate with traditional anarchism, and many might label “radical.” I see this attitude as radical only in that it comes from, and returns to, the root of the problem: namely, how to live on the earth in peace and perpetuity. Each of us has only herself to be, to blame, and to rely upon, and our own behavior is at the root of any social or environmental change. If we want peace, we have to be peaceful. If we want to live in paradise, we have to grow it, now. I see this work as evolution, not revolution, and as the ultimate adventure: a fantastic way to simultaneously enjoy life on this earth and improve it for future generations.

Flowers are not the only thing that bloom in the garden—people do. When people participate in an ecological community, they tune in to the subtle voices of nature and tend to become more attentive to their bodies, more mindful of their impact on the environment, better at listening and communicating, and more able to overcome fears and obstacles.

By putting our hands in the soil, we gain access to the wisdom of the earth, and by putting our heads together we learn how to use that knowledge for the benefit of all. When the members of a community start living more ecologically, they improve the soil, purify the water, plant trees, encourage wildlife, and reduce pollution and waste. By giving back more than it takes, every ecological project increases the overall health of our planet—and thus our capacity for peace and sustainability.

People balk at this vision, call it unrealistic, even fear it. Indeed, it is hard to imagine such a community in these grim and violent times, but with a devoted effort I think we can achieve peace and sustainability through paradise gardening, ecological design, and grassroots community interaction. These varied strategies and techniques help renew our connections to our instincts and enable us to ask the questions that will lead to real, long-term solutions. And once we learn to ask questions—relevant, useful questions—then nothing can stop us from learning what we need to know.

How to Use This Book

The primary goal of this book is to give tangible shape to these ideals, and to show how easy it can be for you and other people who care about the earth to grow gardens and build communities accordingly. We’ll start with gardening, then move on to communities.

The first half of this book focuses on how to establish and maintain ecological paradise gardens, using the resources we have available here and now. We will tap into the wasted resources around us and look at the varied elements of the garden, including the water, soil, plants, and seeds. Then we will use my own ecological design formulas to bring these elements together into a multifunctional, low-maintenance paradise garden.

The next several chapters go beyond the garden to show how the ecological skills learned there can help improve our communities. Here you will find examples and suggestions for meeting people, forming collectives, and organizing projects such as seed swaps, community gardens, educational performances, or workshops on any range of topics. I finish with a special chapter on integrating children into our gardens and community projects. I also include a resources section to help you find more information on the topics in this book and connect with like-minded people in your community.

Unfortunately this book alone will not solve all your problems; nor will it teach you everything you need to know about organic gardening, sustainable living, or community organizing. What it will do is ask the question How can human beings thrive together, in peace and perpetuity, without destroying the ecology that we depend upon? and identify some potentially viable answers, starting with growing and sharing food where you are now.

I am not trying to prescribe a template for a perfect, “sustainable” culture. You must design your own life, your own community, around the ecology you live in. Nor am I telling you to don a loincloth and live on grub worms and roadkill. You must find your own niche in your community, make the best use of the resources at hand, and work with steadfast intention toward a long and natural life.

Ultimately the best way to learn these skills is to do them. Just reading this book won’t get you much farther than the armchair—you have to get out there and try this stuff in your own yard, in your own community. To these ends, I offer you some theories and examples, and a thorough list of references for further study. What you do next is up to you.

By putting our hands in the soil, we gain access to the wisdom of the earth.

Notes for Chapter 1

1. Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986). As quoted in Ronald T. Simon and Marc Estrin, Rehearsing with Gods (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2004).

2. As quoted by Scott London on www.london.com/insight, 25 October 2003.

3. Kenny Ausubel, Seeds of Change (New York: HarperCollins, 1994).

4. Among the additives typically banned are hydrogenated fat, aspartame (artificial sweetener), and monosodium glutamate (MSG) (ibid.).

5. Ralph Nader, from the foreword to Martin Teitel, Changing the Nature of Nature (Rochester, VT: Park Street Press, 1999).

6. As quoted by Vandana Shiva on www.twnside.org.sg/title/trials-cn.htm, 18 November 2005.

7. Organic Consumers Association, “OCA’s Guidelines for Local Grassroots Action,” www.organicconsumers.org/cando.htm, 18 November 2005.

8. Grace Gershuny and Joe Smillie, The Soul of Soil: A Soil Building Guide for Master Gardeners and Farmers, 4th edition (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 1999), 50.

9. Tom Dale and Vernon Gill Carter, Topsoil and Civilization (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1955).

10. It was through this evolution that a group in Montreal formed around the same time, also calling themselves Food Not Lawns but with a slightly different focus. Though both groups formed without knowing the other existed, we eventually made friends and continue to share resources and information.

11. Sarah Robertson, “History of the Lawn,” Eugene Register-Guard, 26 April 1995.

12. Richard Burdick, “The Biology of Lawns,” Discover Magazine 24, no. 7 (July 2003).

13. Joe Hollis, “Paradise Gardening,” in Peter Lamborn Wilson and Bill Weinberg, Avant Gardening: Ecological Struggle in the City & the World (Seattle, WA: Autonomedia, 1999), 154.

14. Bill Mollison, Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual (Australia: Tagari Publications, 1988).

15. Maddy Harland, “Creating Permanent Culture,” The Ecologist 29, no. 3 (1999), 213.