“In many ways, the environmental crisis is a design crisis. It is a consequence of how things are made, buildings are constructed, and landscapes are used. Design manifests culture, and culture rests firmly on the foundation of what we believe to be true about the world. . . . It is clear that we have not given design a rich enough context. We have used design cleverly in the service of narrowly defined human interests, but have neglected its relationship with our fellow creatures. Such myopic design cannot fail to degrade the living world, and, by extension, our own health.”

—Sim Van Der Ryn and Stuart Cowan(1)

“Through design we have the opportunity to participate in this relationship with nature by applying the ethics we hold toward the earth as a whole, or macrocosm, to our given site, or microcosm. When these ethics are applied correctly, the design, once realized, is synaesthetic, eliciting a sensory response from its human occupants. Nature responds to the human input by taking on certain forms (growth). Humans respond to nature’s input by experiencing joy and a heightened awareness (growth). When this level of interaction with nature is achieved, human intervention is not so apparent, and appears to be ‘naturally’ occurring. Examples of this are visible in the habitats of many indigenous peoples who are truly ‘one’ with their environment. The degree of beauty inherent in functional design is evidence of how closely connected the designer is with nature.”

—Patty Ceglia (2)

Bringing It All Together

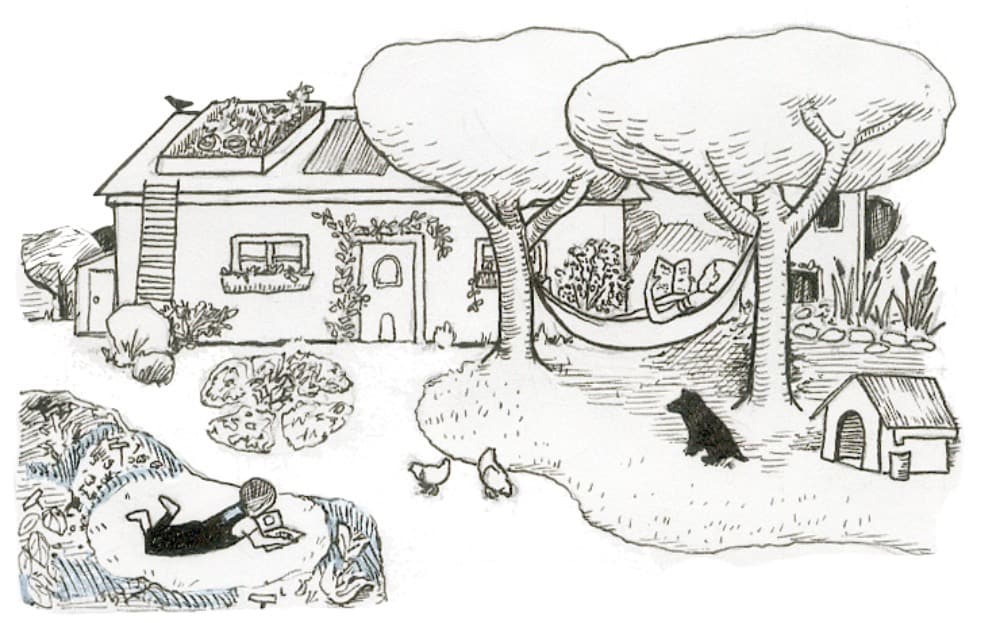

Now that we have seen how to improve the ecological integrity of the elements in our garden, the next step is to assemble those elements into a functional whole. The ecological gardener assumes that every garden is linked with the larger community, which includes not just the natural setting but also the social and economic cycles within.

We develop this link through developing a proactive natural design that emphasizes the creation of functional and ecologically harmonious relationships, starting with the garden and spiraling outward.

Thus the water cycle connects with the plants, waste in the house becomes compost, surplus food, energy, and information recycle into the community, and so on. The success (or failure) of these relationships depends upon the lasting integrity of the overall design, which evolves and adapts alongside the elements within. Whatever types of project you choose, whether a home garden, a large scale community program, or anything in between, design is the process by which your vision becomes reality.

Whether we realize it or not, all of us are ecological designers; for good or ill, much of what we do is design work. When we forge a path, plant a garden, or put things away in the kitchen, we are designing. When we make a list of things to do, we are designing. Anytime we interact with people and objects, we are designing a system, and if that design becomes intentional then we gain access to the full potential of that system.

Defined as the “shaping of matter, energy, and process . . . a hinge that connects culture and nature through exchanges of materials, flows of energy, and choices of land use,”(3) design is all around us. From the shape of our shoes to the layout of our cities, someone designed every human-made thing we see. And all design is ecological design in that it either hurts or helps nature, whether it was intended to or not.

By developing an ecological design we can unite our ideas with nature’s resources and create truly thriving homes, gardens, and communities. As ecological designers, our goal is to become central participants in a self-reliant, diverse, and productive ecosystem that includes not only our own homestead but also the whole community in which it resides. This includes biological and ecological contexts as well as social, economic, and other human concerns. And because this is such a lofty goal, it is essential that we develop a cohesive yet adaptable plan of action.The design process clarifies our goals and ideas, gets them on paper, and provides a road map for implementation. A carefully thought out written design saves time and money, prevents mistakes, and helps communicate ideas to others. It is much easier to correct mistakes on paper than on land. Of course, your long term needs and goals will change, and a good design leaves plenty of room for those changes.

This is not to say that we should attempt to redesign every inch of the earth; wilderness areas should be left as such, and even the most meticulous design is not complete without a little room for the inevitable and ubiquitous chaos of nature. However, we should, indeed we must, reevaluate the function of our current human settlements and develop detailed plans to implement options that are more ecological.

We must go beyond human sustainability to embrace a vision of humanity that is not just surviving but able and willing to truly thrive, in perpetuity, while actually regenerating and contributing to the natural environment. In this way we replace unconscious evolution with conscious natural selection and rejoin the whole as willing stewards of the earth.

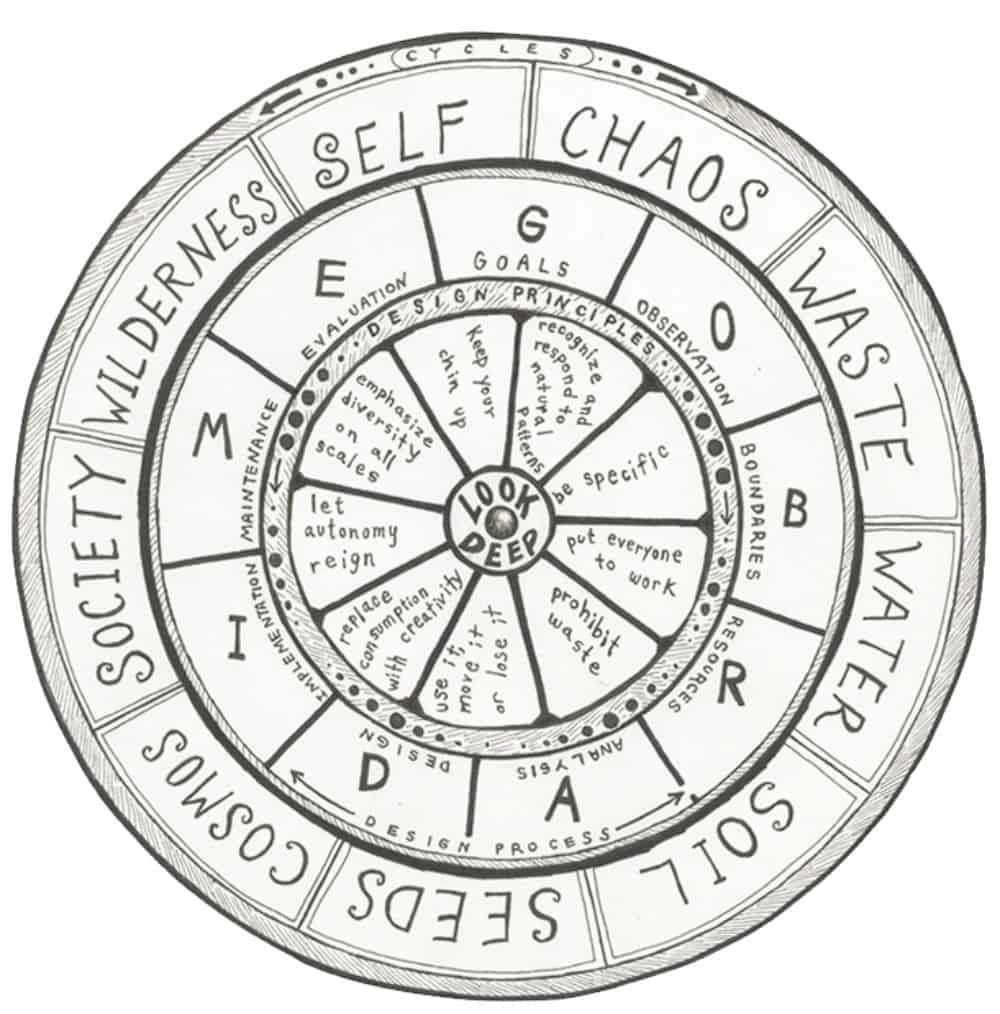

The Spiral Design Wheel

If we are to live in harmony with nature, it needs to feel natural. We have to integrate the notion of ecological design into our regular lives and make it easy and fun for our friends and neighbors to follow suit.

Over the last several years, I have become increasingly fascinated with ecological design theory. I have studied several different approaches, including permaculture, biodynamics, natural farming, and ornamental landscaping and have pulled my favorite parts together to build a simple and practical formula that can be used by anyone on a variety of projects, regardless of academic or practical training. I call this the “spiral design wheel” and have used it to design a variety of projects, including some of those described in this book.

I will explain each phase of the wheel in an order that makes sense to me, but it doesn’t matter whether you jump around a little. Ecological living is not a linear process any more than we live in a linear world. There is no starting or stopping point—the whole design evolves simultaneously, and parts of it change and grow depending on what you’re working on at the time.

To develop a basic plan of action, I recommend a process called Gobradime, which is an acronym for Goals–Observation–Boundaries– Resources–Analysis–Design–Implementation–Maintenance–Evaluation.(4) Now is the time to get out your garden journal and review the observations, resource lists, plant lists, and other design notes that you have accumulated so far. Through the following process, you will use these notes to develop a whole-system design and a timeline for implementation. If you haven’t been making lists and keeping notes yet, don’t despair—start now.

Above all remember that your project, if it involves people and especially if it involves plants, is an organism rather than a mechanism.This wheel, just like any system, is most effective when coupled with a good degree of common sense and natural intuition. Trust your instincts and use the formula to help you refine them. Be careful not to become obsessed with controlling every aspect of the design.

The process of moving through each little step can seem a bit tedious, so don’t try to do it all at once. Do take the time to work through the entire process on paper before making any changes in the garden, at least as a loose brainstorm—trust me, you will thank yourself later.

Look Deep

Remember that bit about observation and record keeping, about microcosms and macrocosms, in the beginning of chapter 2? Go back and reread it. Prolonged and thoughtful observation is better than protracted and thoughtless action.

Looking deep is our best strategy for solving problems, from choosing what to grow to learning how best to contribute to the community. Learn to read the land. Become a good listener. Attune yourself to the cycles of nature.

Observation is at the very heart of ecological living and is the key to finding and cooperating with nature’s patterns and cycles. Lie down on the ground and look at the world around you. What do you see? How do you want to change it? What is the most effective and most ecological way to proceed? Take your time, make educated choices, and try to avoid irreparable errors.

We find the words LOOK DEEP at the center of the wheel, to remind us to return to our observations again and again, through every step of our work, using all of our senses to determine what steps to take—or not to take—next.

Gobradime: The Design Process

Gobradime is a formula for the design, development, implementation, and perpetual maintenance of any project, small or large. Whether you use it exactly as is or sculpt it to fit your needs, this systematic process helps you cover all the bases and stay organized while putting your dreams into action. It works at any scale, for organizing a closet, installing a small garden, developing a whole site, or organizing a bio- regional resource alliance.

Use it to design your home garden, in each layer of the design, and again for the whole. Just as you will apply multiple patterns of nature, you will also apply multiple layers of design. Try it, and you will be amazed at how easily it all comes together.

Step One: Goals

The first step in any design is to identify personal and collective goals. What do you need? What do you want to accomplish and why? What will be the outcomes of your work, and how do these reflect your ethical ideals and practical limitations? Remember, it is much easier to redesign on paper than after the project is half built.

Documenting the design process on paper creates a means for communicating ideas with others, provides a realistic plan for successful implementation, and, later, gives you something to refer back to when evaluating the effectiveness of your work. Write down a list of goals and prioritize them by going down the list and rating each goal on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 representing the highest priority. Then sort the list so that the things you want to accomplish first are at the top. This will help you develop a timeline later on.

Refer back to these lists often, to keep yourself on track and get ideas for future projects, but don’t get bogged down in the idea of accomplishing something that doesn’t continue to inspire you. Goals are like flowers—some of them come back every year, and others last only a season. Our goals should change as we do, and any good design allows for this perpetual change.

Step Two: Observation (and Objectives)

Though looking deep is an important part of every step of the design process, here is the point when we use our powers of observation to make sense of our individual goals. Remember that this is not a linear process—you should spiral around to every step again and again, over many years, as you hone and perfect your design.

With every goal comes a family of objectives, which make up the strategy for achieving the goal. For example, the goal of building garden soil that is ecologically sound will include objectives such as building compost, finding good sources of mulch, and planting cover crops. Thorough observation is the key to developing realistic objectives that will bring you quickly and efficiently closer to your goals.

Go through your list of goals and compare it with the observations you have made so far. Go back out and look deeper, with each goal in mind, to determine which objectives will help you meet that goal. Write it all down, listing basic observations such as “Northwest corner is very shady” and noting ideas for potential action, such as “Plant shade lovers in northwest corner.”

Also look for the social and ethical components of your project. For example, is there a gathering place? Do you need one? How do all of the elements affect one another, and how will people and other inhabitants benefit from a new design? Where are the problems, what are the challenges, and how will changes improve the ethical standpoint of the site?

This process also works quite well for designing community projects, such as skill sharing events, seed swaps, collective gardens, and more. In community work, observation means looking for other activists, finding out what they are doing, and determining ways to integrate your collective vision. Can you plug in with them, or is your idea a new one to the area? What are the obvious and demonstrable needs for your project? Is it worth doing? Carefully examine each of these questions against your ideas and goals, and choose a project that will be simultaneously fulfilling for you and effective for the community.

Step Three: Boundaries

Now is the time to find and establish boundaries. This means everything from physical boundaries such as property lines and flows of energy to personal boundaries like how much time you want to spend in the garden and how hard you want to work.

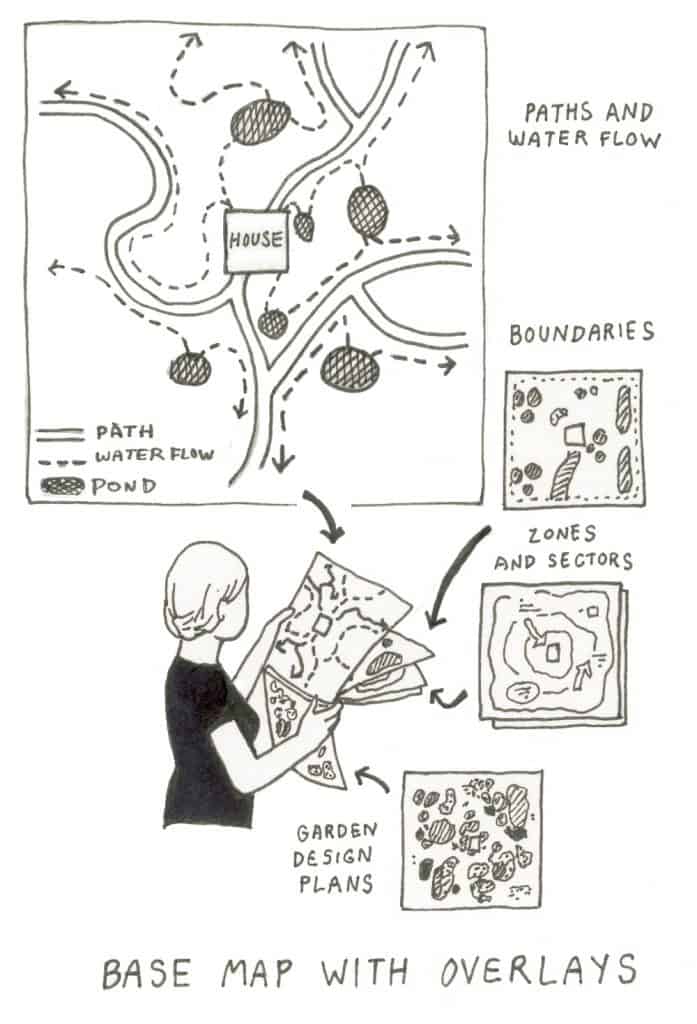

For a site design this step will include drawing up a base map of the site. Pace or measure each distance on the ground and do your best to develop a map that is to scale. Note the following things on the map: lot boundaries, buildings, doors, decks, patios, driveways, fences, hedges, trees, gardens, and any other physical objects on the site. Add in permanent and temporary paths, and make note of any objects that may be temporarily missing, such as parked cars or seasonal motor-home storage.

Now document the flows of water and of human and animal traffic through the site, using dashed lines and arrows. This will establish the main paths through your design. Moving a well-trodden path is rarely a good idea; it is much easier to adapt the design to behavior patterns, rather than the opposite, so go with the flow.

This map will provide the basis for your design—make multiple copies or use transparent tissue paper to overlay new ideas and to develop a multiphase implementation plan. If you are developing a community project, the map might be more of a brain map or timeline for the project, with the varied commitments of participating individuals noted along the sides.

Other types of boundaries will include legal, political, or social issues such as land-use laws or potential issues with the surrounding community. You should also consider the boundaries of what you call your community, but I’ll get into this in the next few chapters. For now just try to foresee any barriers to your projects and note them for later analysis.

Finally, define and document your own personal boundaries. Where and when will you work? Where and when will you rest? Whom will you work with and how? How long do you want to be involved with the project? Should you develop it in a way that others will be able to take over when you move on? How much money do you want to spend?Start small and accept help.

It is virtually impossible for one family on a small urban lot to be totally self-sufficient. If we can work together as a neighborhood, however, we can easily create self-reliant bioregional communities that meet their own needs while stewarding the natural ecology.

Each single being has potential to make exponential effects on the whole, and it is up to you to determine which of these butterfly effects you choose to initiate. Meanwhile, set clear, realistic boundaries and communicate them to yourself and the group you work with. This will help you avoid burnout and frustration later on. Take your time, do the best you can, and see stewardship not as work but as life, now and forever.

Step Four: Resources

Now you start assessing and assembling the varied resources you will need to put these big dreams into action. Go back through your observations and start making lists of the resources available on-site. List existing biological resources, waste materials, and potential sources for more. Make an overlay or copy of your base map and note every potential resource, such as water, sun, compost, manure, wood piles, and neighbors who might like to volunteer.

Ask yourself:

- What’s there?

- What can we do without?

- What do we need?

- Where can we get it for free, or with the minimum output?

Types of resources include money, labor, garden supplies, building materials, access to facilities, and information from experts.

If you can’t find what you need for free, try to innovate something that will fulfill the same function. Often a customized, handmade solution is the most effective. Our most powerful tool for building an ecological culture is our own creativity. Use it. Your imagination is renewable, easy to find, and free, limited only by your own mind.

Also, tap into the information resources available through local libraries and bookstores, and learn as much as you can from that ever expanding space age miracle, the Internet. Do some research and see whether anyone else has solved the same problem or shared the same goals. You should never copy anything exactly, because every design should be site-specific, but usually another person’s solution is easily adapted to a similar problem. If it still seems impossible, try reassessing your goals—just a little—to make room for an alternative plan that makes good use of the resources and ideas you have now.

As you assemble lists of what you have and what you need, it will become apparent that you don’t need everything all at once. Rather, there will be a flow of resources in and out of the project, the nature of which will change and evolve over time. Try to envision this flow, organize your lists in chronological order, and layer them into your timeline and phase plans.

Step Five: Analysis

Analysis helps define weaknesses and ways to overcome them and brings random ideas together to form a cohesive plan. Through this process you will determine how you can use the resources available to you to achieve the goals you have set for yourself, with the greatest amount of harmony with what is already happening and in line with your ethical and practical limitations.

Now you can bring together the stacks of notes you’ve assembled so far and synthesize them toward a tangible design. These notes, though always expanding, should include at least the following information:

1. Observations from around your yard and neighborhood, made over a few days or a few seasons.

2. Goals and proposed objectives, sorted by priority.

3. Catalog of local and surplus resources, including organic food, land, water, tools, mulch, plants, seeds, and building materials. You will add to this list with almost every new observation. Date each entry and note locations where possible.

4. Base map.

5. Notes about personal, ecological, and other boundaries.

6. The water cycle: maps of land contours, drawings of rain

catchment and graywater ideas, and brainstormed lists of

tasks and project ideas.

7. The soil conditions: existing weeds, moisture content, structure and depth of topsoil, and types of insects and worms.

8. Ideas for bed designs and notes about existing microclimates and plans of action.

9. Plant lists: what you like to eat, what you want to grow, companion plants and polyculture ideas, sketches of multidimensional plantings, species lists for what you have and want to get, and potential sources for propagative material.

10. Seed lists: again, what you have, what you want, and where to get it. Also note present and future selection criteria and breeding ideas.

There are several good ways to analyze your notes and get them ready to plug into your design. First just reread all of your notes and brainstorm a list of tasks and project ideas. This pushes the analysis away from theoretical ideas and toward concrete action, which is what you want.

Next, try the zone and sector analysis method described in the “Zones and Sectors” sidebar found below. This will help you place elements in locations relative to their needs and outputs, and it is the first step toward bringing your assorted home and garden projects into a strategic whole. Take a copy of your base map, go through your list of tasks, and place each activity into the proper zone. Also do this with each element, such as the herb garden, the tool shed, the pond, the slime monster, the chicken coop, and so forth. Make little notecards and move them around on the map to consider the effects of varied combinations. This will show you what work needs to be done where and what your options are for the specific placement of each item.

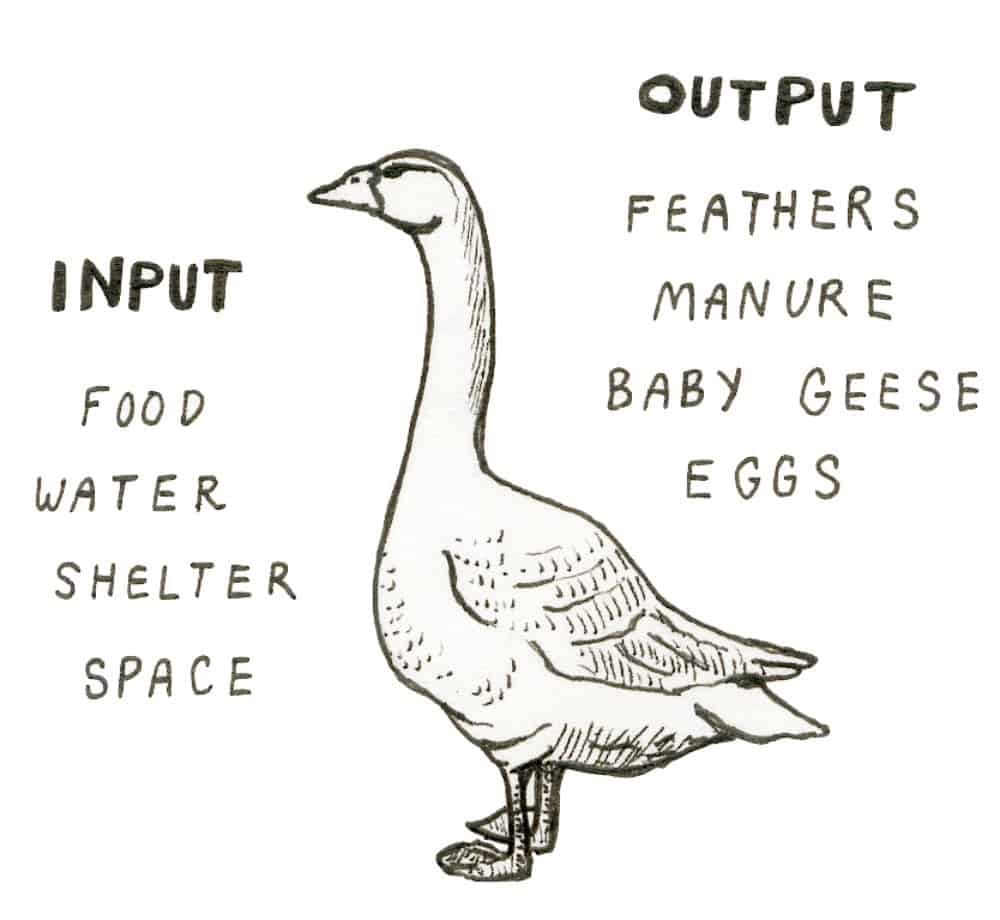

Another helpful tool for analyzing needs against resources is called input–output analysis. Choose any element of the design, whether the whole garden or a single plant. On one side of a piece of paper list all the contributions that element makes to the whole. On the other side list the needs of that element and the resources it requires to function. Do this with several connected elements, and look for ways to overlap needs with resources and surplus with shortages.

Throughout your analysis, ask questions such as:

- What are the economic and ecological costs to implement and maintain the design?

- What are the yields and how can they be improved?

- Where are the imbalances and how can they be corrected?

- What work can we avoid doing?

- What are the best and worst places for each element?

- How is everything affecting everything else?

- How can we use what is available now to turn problems into solutions?

- If nothing was here, what would we bring in?

- How can I best adhere to my ethics and principles, with the least amount of input and the greatest benefit to myself and the earth?

Develop your own lists of questions and criteria, based on your specific circumstances, and use them to evaluate each new opportunity. Find the connections between elements, think about the relationships and how you want to change them, and start choosing where and when to implement each change.

This is also an excellent time to review the ecological design principles described later in this chapter and to measure the ecological integrity of each part of your home and garden. But remember, do not get bogged down in linear analysis or you’ll bury yourself in the paper trail before you ever get a chance to get dirty in the garden.

Finally, don’t overlook the value of intuition, aesthetics, and random assembly as design tools. Sometimes just putting a plant or other element where you think it looks nice, or where you happened to set it down first, works better than anything else.

If you get stuck, try using a process of elimination:

Ask yourself, where shouldn’t this go? and see where that takes you.

Step Six: Design

Now you are ready to develop a multiple-phase design and plan for implementation. Go back again to your notes, starting with the ten items listed above, and choose a plan of action according to your analysis of the information you have available. Go through everything again and write a list of actions that will bring your visions into reality.Continue to prioritize these actions by sorting them according to which goal they help to meet and how important that goal is to you.

Make several copies of your base map and begin placing your tasks and elements in location relative to their needs and outputs. Think well in advance, and develop several phases to complete over the next several years. For each phase develop a different map and write a loose budget to accommodate that phase. Write down how many labor-hours you estimate for each step and determine ways to find the help and the funds that you need.

If you follow these steps, you will end up with a handful of maps and lists, sorted into chronological order according to priority, all laid out according to where each action will occur. Now you just have to start going down the list and getting the work done.

Step Seven: Implementation

Hang up the maps, notes, and design plans on a central bulletin board where everyone can see them. This is the time to stop writing and start actually moving stuff around. Do take time to jot down notes as you develop new ideas or make changes to the original design—this will save time later when you evaluate your work. Also, be sure to take plenty of time to step back, rest, and reflect on your progress.

It is easy to become consumed with the first phase of implementation, but pace yourself so you stay sane and are able to follow through with the rest of the plan. Don’t burn yourself out. Take your time and focus on doing less right, rather than more wrong.

Remember to feed and hydrate yourself and other volunteers, and try to work things out if people become agitated or have trouble working together. See chapter 11 for tips on working with groups. In general, be compassionate and true to your goals and ethical commitments, and have fun putting peace into action!

Step Eight: Maintenance (and Monitoring)

As implementation progresses you will need to monitor and maintain existing systems. Some people develop detailed forms to document the data generated by their projects, such as growth rates, yields and potential yields, and climatic patterns. The point is to find and record successes and problems (including potential problems) with the design, so you can either repeat patterns or go back and rework them to improve the whole.

Ideally, in a home system you will be living in and interacting with the design as it comes about. Pay attention to the ways in which your life improves or becomes more difficult through these changes, and adjust your design patterns to best embrace the personal patterns of yourself and the other people involved.

Step Nine: Evaluation

As each phase is completed, get together with your working group and evaluate your progress. Identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and challenges, and compare notes about what should change or what is working well.

This step is often overlooked by tired and overwhelmed activists who just want to move right on to the next phase of the project. However, evaluation is the key to a sustainable and realistically evolving plan, and it is of the utmost importance that we each set aside enough time to effectively and productively evaluate our work against our original goals and against the ethics and ideals we have chosen.

Write down your evaluations and attach them to the maps and notes from the appropriate phase. As you evaluate, you will discover new goals, new ideas, and new ways to improve the efficiency and ecological integrity of your design. When you are ready, start again with the G and continue to spiral through the process. And, of course, don’t forget to evaluate your actions and ideas against the next ring of the design wheel: the ecological design principles.

Zones and Sectors

Many ecological designers use permaculture’s zone and sector analysis system. Zones represent patterns of human use, while sectors are the natural influences on the project. Make an overlay for each on your base map and use the descriptions below to determine how to place the elements in your garden and home system in a way that makes practical and ecological sense.

Sectors

Sectors are the wild and/or uncontrollable influences over the site. The primary sectors in most gardens are sun, shade, wind, frost, wildlife, fire hazards, and varying levels of moisture and soil fertility. On an urban site other uncontrollable influences might include car noise, the neighbor’s cats, or that ugly billboard that you can see across the alley. Be sure to consider “Sector C,” or the influence of children on your site. See chapter 12 for more on this topic. Make note of as many sectors as you can find, and design your garden to accommodate or overcome the opportunities and obstacles they present.

Zones

Zones represent patterns of human use, and placing elements into the appropriate zone will save heaps of time and money. Some items, such as water collection, composting, wildlife forage, and sacred spaces, will be woven into several zones.

The junctions between zones, between sectors, and between zones and sectors will yield edge effects like increased diversity and specialized microclimates. Look for and note these opportunities, and compare them with your needs and resources. Try to develop a concrete vision of how people, energy, and materials flow through the project, and draw these patterns on the map.

- Zone 0: Yourself, your personal cycles, your relationships, and your behavior.

- Zone 1: Most intensively used, closest to home.

- Includes house, greenhouse, workshop, kitchen gardens, compost, chickens, and anything else that needs daily care.

- Zone 2: Intensively used, very near home. Includes secondary greenhouses, larger gardens and composting areas, water catchment, solar shower, sauna.

- Zone 3: Regular use. Includes some external structures, field crops, larger water storages, orchards, and recreational elements.

- Zone 4: Minimal use. Includes timber, more field crops and fruit trees, forage pasture, mushroom cultivation, and more large water storage.

- Zone 5: Unmanaged. Used for minimal foraging and recreation; left as a wild area for nonhuman species to inhabit.

Zone and sector analysis is an excellent way to begin placing elements onto a site. Most urban homes have only the first two or three zones, and a whole system design must contain all of them. In the country zones 3 and 4 would include field crops, fruit trees, and a woodlot. In the city these zones might extend into a local park, a neighbor’s house, or a dumpster, where you grow or acquire more food, building materials, and fuel. Zone 5 becomes your effort toward the restoration of local wild areas.

Proverbs for a Peaceful Evolution: Ecological Design Principles

In every book or course on permaculture or ecological design you will find a set of design principles: short phrases meant to guide the designer toward results that harmonize with nature. When researching this book, I came across no fewer than 50 different principles, each with their own piece of wisdom for the would be earth steward.Based on research, natural law, and experiential knowledge, these principles came from some of the greatest minds of our time—Jude Hobbs, Tom Ward, Toby Hemenway, Rosalind Creasy, Graham Bell, Bill Mollison, Sim Van Der Ryn, Stuart Cowan, John Todd—ecologists and educators who grow diverse organic gardens and whose ideas have changed the way millions of people treat the Earth.

I thought about listing all 50 principles, but instead decided to synthesize them into my own set—short, sweet, and easy to remember. I humbly offer you the results below and hope they will help and inspire you to solve design problems throughout every aspect of your life.

I will explain each principle, then list a few sample strategies that you can use in your garden. You will remember some of these ideas from the previous chapters—indeed, we have seen examples of each principle in every element of the paradise garden. Now we bring them together.

1. Emphasize Diversity on All Scales

Again we find diversity at the top of the list. Nature is not single-minded, and neither are we. This variety is our number one resource and, thus, our first priority. This includes using a diversity of resources and strategies, as well as holding diverse views and having diverse goals.

Work toward a diverse community, human and otherwise. Remember that diversity is alive, and that to conserve it, we must grow and interact with it. Simply, if you devote your landscape to growing as much diversity as possible, you will not fail in your quest for paradise.

Sample Strategies:

- Build compost from many different ingredients to encourage diverse soil communities that will support healthy plants.

- Grow food in many locations in case one spot fails to yield.Establish multiple pathways.

- Eat many different types of food to encourage a healthy body.

- Work with different kinds of people to increase your under-standing of other cultures.

- Create edges around the garden to enhance the diversity of species.

- Catch water at several points and direct it into different parts of the garden.

- Grow seeds of different varieties each year and save seeds for many reasons.

- Look for unusual ways to solve problems and look past the first or most obvious answer.

- Leave parts of your landscape wild to encourage nonhuman benefits.

- Never pull a plant you don’t recognize—make weeding an educational and intentional experience.

- Let every species in your garden go to seed at least once every few years.

- Grow things that yield in the winter or off-season to ensure a year-round food supply.

- Always look for new information and don’t get set in your ways.

- Meet needs with multiple resources, such as collecting mulch materials from several places.

- Make each resource meet multiple needs, such as using a greenhouse to grow plants, heat water, and store tools.

2. Recognize and Respond to Natural Patterns

The power of nature is far greater than the strength of any structure, so why not tap into some of that power and make things easier on yourself? Nature (including you and your garden) is not just a bank of resources; she is an ideal model of evolving ecological systems, and we can look to her for guidance at any phase of our planning. Inspired by nature, we offer our ideas and she provides the ways and means to vitalize them.

Many of the best examples from nature manifest themselves through specific, repeated patterns. We need only look at a leaf, a trickle of water, or our own fingertips to recognize the familiar branching, swirling, or webbing pattern, each only one layer in the complex matrix of flows, links, and connections that unite us together with all nature’s mystery. For centuries people have used natural patterns to design gardens and communities, and through understanding these patterns we can use them to solve design problems.

For an excellent overview of nature’s most common patterns, see Peter Stevens’s book Patterns in Nature.

Much of what we do every day works against nature, and changing the dominant paradigm does not happen overnight. However, we can move in leaps and bounds if we make every effort to go with the flow. If we emphasize cooperation over competition and treat our garden as an organism rather than a mechanism, then we harness the power of nature’s plan without needing to overanalyze it.

Sample Strategies:

- Take a break in the winter.

- Build an herb spiral.

- Use branching patterns for garden paths.

- Mulch every autumn.Use gravity to direct water.

- Let plants go to seed.

- Harvest what already grows there.

- Recognize microclimates and use them.

3. Be Specific

Many varying factors, including climate, topography, social and cultural paradigms, and of course the needs and desires of the designer, require that each design be site-specific. Deeper, each detail of that design, from the shape of the kitchen garden to the species of thyme, should be chosen through a new and careful process, rather than by imitating a book or other example.

Architectural designer Patty Ceglia writes, “The design process should generate its own solutions, structure, technologies, connections, and aesthetics. Don’t automatically copy someone else. Never apply [an idea] just because you’ve seen it before.”(5)

An ecological life has no template—we must adapt and evolve with the ecology around us. Every design should be ultraspecific and should embrace both the strengths and the weaknesses of that site. Start with the needs and functions and break down design components to

accommodate those needs. Determine which questions to ask based on the specific circumstances, then find specific answers for those questions. Make small, slow changes that relate to the exact influences and needs of your site.

Thus, rather than designing a “garden,” with whatever generic elements this seems to entail, we design a place to grow food, to read in the shade, to play with children, and to learn about nature. Each layer adapts to the specific purpose for the individuals involved, and each solution has specific details that are unique to the problem at hand.

Sample Strategies:

- Observe sites where similar problems exist, and adapt solutions to accommodate your own needs.

- Choose specific plants (“wild marjoram (Origanum vulgare) and lemon thyme (Thymus serpyllum)”) for each function, rather than general categories (“herbs”).

- Brainstorm a list of needs and functions, and fill each with a specific resource.Look for details out of place, and adjust them as needed.

- Choose each variety of fruit and vegetable based on local reputation. Don’t settle for just any lettuce when you could have one that will do especially well in your bioregion.

- Learn about all the insects and birds in your garden, and plant what they specifically like to eat.

4. Put Everyone to Work

Take action toward facilitating the flow of resources into working niches, and cover your bases from as many angles as possible. This includes techniques such as multitasking, plant stacking, time stacking, and recruiting volunteers.

You should get something from your work. As they say, you cannot work on an empty stomach, and unless your project provides some sort of physical or emotional return you will lose interest quickly. This interaction with, and enjoyment of, the fruits of your labor validates your ideas and keeps you motivated. By making every detail work to our advantage we increase the sum of yields and get more for our work.

To increase the sum of yields means to diversify and multiply the types of yields we get. For example, a vegetable garden provides vegetables, but it could also provide flowers, compost materials, and educational opportunities. So for the same amount of space, we can get five times as much reward just by planning carefully.

Remember that yield is not the gross harvest—it is the difference between what you put in and what you end up with. Never take the whole yield. Try to get as much as you can from each stage of each element in your system without degrading the ethics of that project. In this way every need is met by multiple resources, and every resource fills multiple needs.

Sample Strategies:

- Choose plants that you can use for at least two different purposes.

- Let insects and birds pollinate your seed crops.

- Make use of every niche and every microclimate.

- Host hands-on workshops and direct the energy toward projects in your garden and community.

- Meet needs with multiple resources, such as when catching water from multiple sources.

- Value all roles in nature, even those you cannot define.

5. Prohibit Waste

The seven R’s of cycling are: Rethink, Redesign, Reduce, Reuse, Repair, Refuse, Recycle. Put every element, every yield, and every potential waste through these steps and see if you can close the loop.Go back to the section on cyclic opportunity, in chapter 3, and make sure you are tapping the flow wherever possible.

Each time a resource is lost it must be replaced or the system will falter and change. Conversely, unused surplus can become pollution. Some designers view pollution as evidence of an incomplete design. By replacing used resources and finding uses for our surplus, we strengthen and create more yields for the whole system and improve the overall integrity of our design.

This principle also calls for the recirculation of knowledge: I teach ten people, they each teach ten more, and so on. In this way we can exponentially share useful skills and information and incite new projects everywhere we go. Exponential learning makes it possible to share large amounts of knowledge in a short period of time. By empowering others through communication and setting examples, we can spread stories of peace in action and connect needs with resources across the globe.

Sample Strategies:

- Use found items such as cardboard, wood, metal, and plants to build perennial gardens.

- Compost everything you can, from garden and kitchen debris to paper, human wastes, and old clothes.

- Find or create outlets for your surplus: start with Internet lists, free boxes, and food banks.

- Buy nothing new, and start at the waste stream when looking for resources.

- Let your mistakes be tools for learning, and keep meticulous notes to help avoid larger mistakes later.

- Replace used resources in nature by planting trees and participating in restoration work.

- Work through the cyclic considerations discussed later in this chapter and close the loop wherever you can.

6. Use It, Move It, or Lose It

Place each element in your design in a location relative to its function. If you spend an extra fifteen minutes every day going out of your way to look for something, you waste almost four days a year that you could use for a vacation or creative project instead. Like putting the soap near the sink, so too can we place every useful item just where we need it.

If you can’t find a place for something, maybe it doesn’t belong onsite at all. No matter how useful an item may seem, if you don’t use it, consider letting it go. Open space provides room for new ideas, and someone else may need just that item for a special project. Sometimes surplus stuff represents things you think you want to do with your life but haven’t made the time for. Perhaps it’s time to admit to yourself that you may never actually restore that old Chevy truck, and maybe you’d rather have the driveway for a greenhouse instead.

Sample Strategies:

- Build compost in the garden, rather than in a bin off to the side.

- Store water barrels wherever you need water, such as near the shower, doghouse, chicken yard, and garden.

- Store different types of tools in the areas where you need them, rather than keeping them in a central tool shed.

- Eliminate dead space by moving out unused items or taking down walls and fences to open the flow.

- Notice microclimates and grow in each what will do well there.

- Get rid of anything that hasn’t been used for three years or more. Life is too short to keep the same stuff the whole time.

- Rearrange your house and yard to reflect what you do there, not what the rooms are called.

- Cook on the patio, do art in the kitchen, sleep in the garden, and turn the bedroom into a dance studio.

- Literally, don’t just think but eat, sleep, and live outside the box!

7. Replace Consumption with Creativity

Start small and work outward. It is better to have a small, functional system than a large, dysfunctional one. Rather than planting a huge, intricate garden across every inch of your yard and then attempting to maintain it while conducting the rest of your life, create an integrated system of spaces that encompasses what you want to eat, what you want to do, and how you want to live.

Localize your needs, simplify your desires, and look for the solution that will require the least amount of energy. Each choice carries a certain degree of ecological accountability, and the more you can avoid deep embedded energies in items such as fossil fuels, fresh lumber, plastics, and disposable goods, the closer you can come to ecological harmony. Remember, you can’t buy your way to an ecological life—you have to create it.

This principle teaches us to make the least change for the greatest effect. Sometimes an aspect of a design needs only a small adjustment to produce a large improvement. Rather than changing everything around or starting from scratch, we can save time and money when we make what is already happening work to our advantage and generate new ideas in the process. To this end, find solutions in the form of subtle changes rather than added inputs. Instead of looking for what you need to do to improve your garden, look for what you can stop doing that will make it more beautiful, more ecological, easier to maintain, and more likely to meet your goals.

In industrial society we often rate our success according to how much we produce, and how quickly and how large. In an ecological design we evaluate success in terms of how well we conserve and perpetuate diversity, how creatively we use available resources, and how little work is needed to maintain a lush, abundant garden. This principle reminds us that less is more, and that thoughtful contemplation is the first and most important task of every project.

Sample Strategies:

- Glean produce from local farms rather than growing a surplus of the same things.

- Match technology to need—don’t use a tractor to do a shovel’s work.

- Store resources high on-site and let gravity help direct them into the garden.

- Mulch instead of tilling.

- Reproduce local plants from free seeds and cuttings, rather than buying starts.

- Practice voluntary simplicity (see chapter 8).

- Spend a few days resting in the garden, rather than working in it.

- Make hay while the sun shines.Use cardboard instead of landscape cloth under garden beds.

- Make compost tea instead of buying fertilizer.

- Replace industry with information by doing the appropriate research and thinking things through.

8. Let Autonomy Reign

Nature provides many patterns and models for systems that perpetuate themselves without destroying their resource base, and most of these systems self-perpetuate without the need for maintenance or interference by humans. If we can learn to trust nature, we can let her do most of the work in our home gardens as well.

Our best allies in these efforts are the organisms already living around us. We can see that even the smallest insect has an essential job to perform in the system. All creatures work, all plants have a purpose, and beneath every city there are hundreds of tons of bacteria, working all through the year to create and repair life.

If we pay attention to the tiny details, they will provide opportunities for exponential improvements. On the other hand, if we overlook the negative impact of a particular element, then it may inhibit or damage the whole. If we can recognize the function and worth of as many details as possible and increase our awareness of the intrinsic interconnectedness of all things, then we can match needs with resources and initiate new, self-sustaining cycles.

This principle teaches us to look for autonomous yield, and to try to mimic the conditions that created it. Encourage volunteer plants and make things easy on yourself. Let leaves fall where they may and do what feels right in the garden, rather than what garden magazines say you should do. Work toward low-maintenance, abundant systems that will outlive you.

Autonomy and personal responsibility are the tenets of a free society. The more we practice our understanding of them in the garden, the easier it will be to practice them with one another. To do this we must first recognize and value functional interdependence in the garden and in our communities. Only then can we rejoin the whole without losing the integrity of any individual part.

Sample Strategies:

- Use prolific weeds for food, fiber, and mulch rather than eradicating them.

- Let tomatoes and cucumbers sprawl on the ground instead of trellising them.

- Harvest and eat wild foods such as blackberries and maple syrup.

- Make paths where people will walk instead of trying to get people to walk on a new path.

- Use biological resources that will self-perpetuate to solve problems, such as living machines that cleanse wastewater.

- Establish living fences with plants such as filbert, willow, apple, and hawthorn.

- Encourage diverse insect and wildlife populations, and observe rather than interfere with their cycles.

- Ask not what the garden can do for you, but what you can do for the garden.

9. Keep Your Chin Up

This final principle is easily the most useful, and the most important to uphold. Attitude is everything, and in our tolerance and flexibility lie the keys to a long and happy life. If you don’t have fun while gardening, you probably won’t spend much time doing it. Make choices that will make you happy, and that will result in the ongoing enjoyment of your garden space and your life. The garden should be your sanctuary, not just another obligation. Do what comes naturally to you, and create a space that encourages you to be yourself.

Traditional permaculture teaches us several attitudinal principles, such as “Mistakes are tools for learning,” “Problems are solutions,” and “The designer limits the yield.” These ring true throughout every phase of life. If we are not consistently open to change, challenges, and new ideas, we will severely limit the success of our work and waste time trying to keep things the same. Nature never stops evolving, and neither can we. By remaining flexible and receptive to feedback, we become adaptable lifelong learners, so that no matter how impossible the situation might seem, if we keep a good attitude, open our minds, and think creatively, the solution will come.

This principle of flexibility also applies to your body. You can’t work on an empty stomach, and you can’t build a bridge with a bad back. The following strategies include some of the most important things we can do for our bodies and, by extension, the gardens they tend.

Sample Strategies:

- Keep a journal of frustrating moments, and refer to it later to avoid repeated mistakes

- Be kind and willing to negotiate problems with fellow workers.Identify your behavioral weak spots and abuse issues, and work through them with a counselor.

- Spend a few minutes resting each day—show me a workaholic and I’ll show you a shortcut to total burnout. Love your hammock as you do your pitchfork: as an essential tool.

- Listen to the birds, smell the flowers, and take time to enjoy the fruits of your labor.

- Eat well, drink plenty of water, and stretch daily. Stand up straight. Take a few dance classes and learn how to hold your spine correctly.

- Have a dance party in the garden.

- Sleep in the garden.

- Make love in the garden.

- Be proud of your work, share it with others, and welcome their positive and negative feedback.

Our Most Powerful Tool

In his book A Whack on the Side of the Head, Dr. Roger von Oech writes that “the real key in being creative lies in what you do with your knowledge.”(6) Von Oech presents an array of tips and exercises for spurring creative thought. This excellent book, combined with my own experience with bending the rules, inspired the following set of mental tools to help you flush out your brain and let the ideas flow. If you get stuck, use these exercises to help get the ideas flowing.

Seventeen Ways to Get Creative

- Take risks. Do not fear failure—it is just another opportunity.

- Look deep. Look past the proverbial trees and into the subtle details of the forest.

- Ask What if? Speculate, and options will arise.

- Go to new places. Refresh your mind, your settings, and your relationships.

- Go to old places and expand. Return to old ideas, inspirations, and colleagues.

- Be willing to relearn. Question old habits and be willing to unlearn what is no longer useful.

- Change the rules. Evaluate assumptions, question convention, and change often.

- Switch roles. Put on a different hat and swap tasks with others.

- Make work fun. Laugh or quit. Life is too short to waste on suffering, especially if you have a choice.

- Rock the boat. It’s fun, as long as it doesn’t tip over in shark-infested waters.

- Look for more than one right answer. There is usually another solution.

- Spend time thinking. Not working, writing, talking, or meditating—just thinking.

- Spend time not thinking. Let preconceived ideas go, and allow for spontaneity.

- Ask dumb, repetitious, and impractical questions. Ignorance is a blank canvas.

- Write everything down. Carry a small notebook and use it every day.

- Write everything down. Review your notes and file them for future reference.

Write everything down. Keeping records prevents mistakes and leaves a legacy.

Cyclic Considerations

The next ring in the design wheel asks us to consider nine natural cycles. Each of these cycles has a profoundly significant influence on our work, and by working with rather than against them we avoid mistakes and bring our garden into an easier harmony with nature.

We’ve looked at how cycles present opportunities, and how we can interact with a cycle and divert its flow into our projects. Within each of the cycles below there are countless opportunities, between the source and the sink, to increase yield and efficiency. Learning to recognize cycles deepens our understanding of nature and helps us place our ecological selves in context with our natural surroundings.

Through each step of the design process, look at the way your plans might influence each cycle. Also look for opportunities to make your work easier by tapping into what’s already flowing. Several of the nine cycles I emphasize here have been covered in previous chapters, so I will just run through them briefly:

1. Waste. Again, I cannot overstate the importance of recycling waste toward our goals. Remember to look first to the waste cycle for resources, and to avoid sending resources to the sink. See chapter 2 for details.

2. Water. See chapter 3.

3. Soil. See chapter 4.

4. Seeds. See chapters 5 and 6.

5. Cosmos. All gardeners must consider the patterns of the sun, but what about the rest of the cosmos? I strongly recommend also noting the patterns of the moon and other planets through each phase of the design process. They will affect you, your plants, soil communities, and many other aspects of your work.

6. Society. This includes asking yourself what your community needs and what it can provide. Consider the social impacts of your work and look for ways to make it more powerful and more beneficial.

7. Wilderness. Always leave a little bit of your garden wild, and always direct some of your energy toward preserving and perpetuating wild places nearby. When the wilderness goes, we go, so take the time to consider it.

8. Self. Your own cycles are just as important as the rest. How do you feel? What do you need? There will be times when you are deeply inspired to turn your whole town into a paradise garden, and times when you couldn’t care less. Note these patterns and compare them with the other cycles so that you can see when to tap the flow of your own positive energy.

9. Chaos. In the words of John Briggs, “The scientistic culture that has increasingly surrounded us—and some would say imprisoned us—for the last 100 years sees the world in terms of analysis, quantification, symmetry, and mechanism. Chaos helps free us from these confines. By appreciating chaos, we begin to envision the world as a flux of patterns enlivened with sudden turns, strange mirrors, subtle and surprising relationships, and the continual fascination with the unknown.”(7)

Always keep in mind that the natural cycles have their own agenda. Try your best to integrate rather than interfere with them. The more you keep track of your options, the more educated your garden choices will become.

This spiral design process, while it may seem laborious or complicated, will help you bring your garden closer to paradise. These principles and techniques also apply to designing other layers of our lives, such as how we live at home and how we interact with the community.The next few chapters will take us beyond the garden to examine the other pieces of the puzzle, such as consumer choices, community involvement, group process, and working with younger generations to ensure the paradise gardens of the future. We’ll start at home and spiral outward.

Notes for Chapter 7

1. Sim Van Der Ryn and Stuart Cowan, Ecological Design (Washington, DC: Island Press, 1995), 9.

2. Patty Ceglia, “The Process of Creativity: A Holistic Approach to Design,” The Permaculture Activist 12, no. 2 (1991).

3. Van Der Ryn and Cowan, Ecological Design.

4. Gobradime is adapted from several similar acronyms found in Andrew Goldring, ed., Permaculture Teacher’s Guide (London: Permaculture Association, 2000).

5. Ceglia, “The Process of Creativity.”

6. Roger von Oech, A Whack on the Side of the Head: How to Unlock Your Mind for Innovation (Los Angeles: Warner Books, 1983), 6

7. John Briggs and F. David Peat, The Seven Life Lessons of Chaos: Spiritual Wisdom from the Science of Change (New York: HarperPerennial, 2000).