“Slowly, even among the squarest of citizens, the suspicion is growing that it is the very nature of our vastly developed industrial system to produce an environment which is poisonous to our bodies and toxic to our minds. Perhaps the making and buying of goods is not the main goal of a sane society. Perhaps a bigger Gross National Product is not a god worth sacrificing our lives to. Perhaps we must question the whole orientation of American values. The early labor union leader Sam Gompers once summed up the aims of the labor movement as “More!” But maybe now we need less”

—Ernest Callenbach(1)

“Everything needful to be completely human is available to us in the environment—the garden and neighborhood. We can rely on this truth because “humanness” is a creation of the environment, the most recent manifestation of a coevolution between our genes and all the other genes out there that has been going on since the beginning of life on earth. Much chancier is the possibility that everything we need to be completely human is available to us in the city, or through money. “

—Joe Hollis(3)

Stepping Lightly on the Earth

So far most of this book has been about gardening. Not just any gardening, but the type that results in low maintenance perennial edible ecosystems that lend themselves to the long-term ecological health of a bioregion. This is a lifetime’s pursuit, and one that can be deeply fulfilling for the people who do it.

Unfortunately just growing gardens will not convert this wasteful, polluting society into a fruitful and healthy one. Our gardens must not only produce food for ourselves and other living beings, but also create a backdrop for whole communities of people working together to reduce their personal and collective impact on the natural world. Our gardens provide the bounty and the inspiration, but it is us, the gardeners, who must provide the real change.

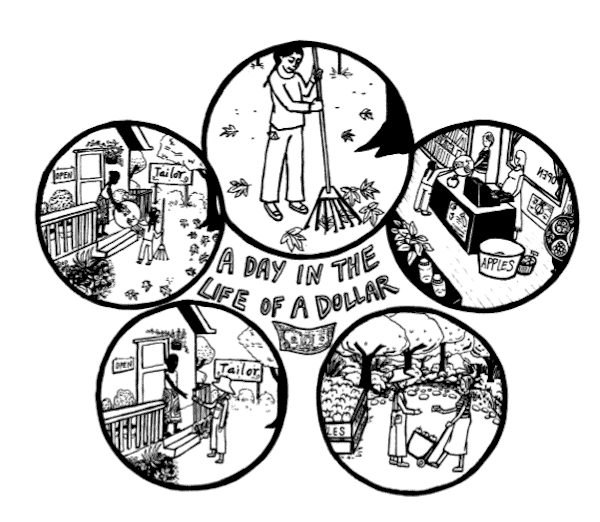

This change comes in many colors. At the top of the list is consumer choices. From what we put on and into our bodies, where we sleep, and how we get around to how we make money and educate children, every choice we make has deep ecological implications. Every time we spend money, there is an ecological choice to make: to harm or to help the earth? And while it may not seem like one family’s changes could affect a whole world, the vast environmental destruction we see today is a direct result of irresponsible, irreverent consumption.

Our consumer choices reflect our lifestyles, and it is these lifestyles that we can and must change to develop and promote more ecological ways. Our individual lifestyles bleed into our families’ lifestyles and into the neighborhoods around us. And as we change as individuals, our communities change with us. Like a butterfly effect, our evolution toward ecological harmony is exponential.

As I said in the beginning of this book, if we insist that our human communities not only provide for their own needs but also contribute to and improve the natural environment, we will move toward a healthy, thriving human ecology. The garden is an excellent place to start, but we must go beyond it to incorporate ecological ethics into every aspect of our daily lives.

Fortunately the design principles I discussed in chapter 7 not only work well in the garden but also apply to the rest of our world. We can improve the ecological integrity of our lifestyles through applying these principles wherever possible. By using the spiral design concept to evaluate our homes, jobs, and communities, we can identify opportunities for sharing space, recycling waste, and eating and growing organic food. I touched on some of these ideas in the first two chapters of this book. Now I’ll go deeper, into an assortment of options and practical strategies.

Some of these options may seem radical, unrealistic, impractical, or somehow intimidating when compared with what is currently familiar. Still, remember that electricity, bleach, petrochemicals, and many of the other things that help maintain this superclean, paranoid culture are all inventions of the past few centuries, and humans have been thriving on Earth for millions of years. Could our recent, rapid decline toward extinction be due to these modern “conveniences”?Could they in fact be harming rather than helping us?

A thorough treatise on the art of ecological living could fill a hundred volumes, but the main point is this: As individuals, neighborhoods, and communities begin to fulfill their needs on a local, more simplified basis, the extent to which they degrade the natural environment decreases. By consuming less, learning to make the most out of what we have, and sharing surplus, we can slow the destruction caused by our culture and improve our personal and community environments.

Get Over It

This chapter is a plea to examine your comfort level and determine whether the things you think you need are enriching or just sugar coating your life. Do you really need all those cars, appliances, chemicals, subscriptions, new clothes, plastic toys, and airplane vacations? Does anyone really want to keep up with the Joneses?

When I tell people I live on about six thousand dollars a year, that I don’t have a refrigerator or hot water in my kitchen, and that I compost my own manure, they think I’m crazy. They say in disgust, “How can you live like that?” Yet this is how the vast majority of people in the world live. Sure, many of those people do not have a choice. They struggle every day to feed their children, stay healthy, and survive in bleak or hopeless poverty—much of which is caused by the exploitation of land, labor, and natural resources by wealthier cultures (like ours).

Yet millions of families around the world find joy in a voluntary simplicity. They grow much of their own food, make the best out of available resources, and enjoy the natural luxury of a simple, frugal life. They go dancing instead of shopping and watch birds instead of television. This way of living increases our connection to the earth, enriches our character, and usually improves our physical health.

Much of the harmful consumption in the United States and other Western cultures is a result of paranoia about germs and disease. We are terrified of bacteria, yet our biology depends on them to survive. Show me a house full of cleaning supplies and I will show you a medicine cabinet full of pharmaceutical drugs.

Vinegar, natural soap, baking soda, a good scrub brush, and some thick cotton rags are all anyone needs to clean a house. The chlorine based chemicals that sterilize our homes pollute natural waterways and cause cancer and ozone depletion. I never use chlorine, yet I rarely get sick, never go to the doctor or take medications, and am physically stronger at age thirty-four than I was at twenty. Without digressing too much, I will just say that you will be doing yourself, your family, and the earth a favor if you never use another chlorine based chemical again.

Everyone has their own comfort level, and it is important to feel safe in our work and living environments; still, it is surprisingly empowering to challenge yourself to let go of what you think you need to make room for the life you really want. Again, this is not a demand that everyone get rid of everything they own and move to a commune in Tennessee; rather, this is a gentle encouragement toward a rational assessment of our addiction to consumerism, and toward taking control of our lives.

It is up to each of us to examine where we are now against where we would like to be and to formulate a plan of action. In general, look at what it takes to furnish what you eat and use, and wherever possible minimize the energy required to support your lifestyle. This is not about being perfect, but about striving for balance. It is about acknowledging responsibility, getting creative, and challenging ourselves to improve. The best we can do is work toward an awareness that will allow us to live comfortably and creatively, and without harming others or the environment.

That being said, here are some options. As you read through, think back to the design principles in the preceding chapter. Many of them will recur here, as we see how lessons learned in the garden apply throughout our lives.

Embedded Energy and Your Ecological Footprint

Everything we use has deep ecological implications. It is easy to overlook the damage our everyday lives do to the natural environment, but we can gain a more tangible understanding of the embedded energy in our lifestyles by determining our “ecological footprint.”

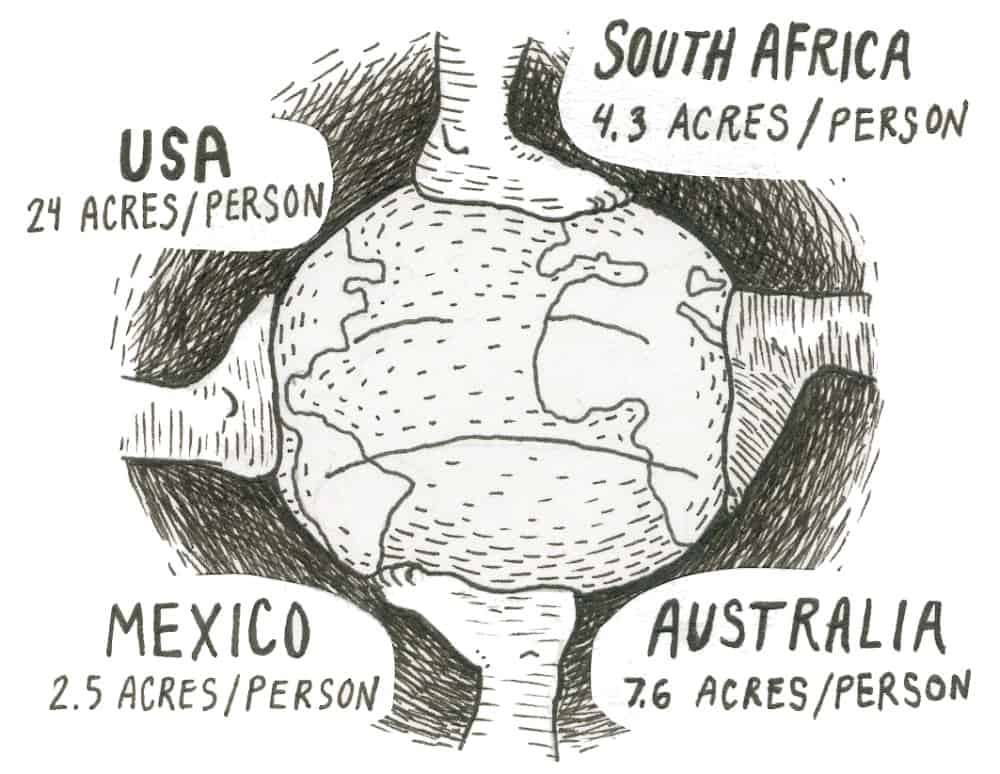

The international Earth Day Network offers an ecological footprint analysis.(4) Through an online questionnaire, you can estimate how many acres of land, in your own country and elsewhere, it takes to produce what you consume. According to this group, the average person in the United States requires twenty-four acres, yet worldwide there exist only four and a half biologically productive acres per person.

This means that if everyone lived like the average American, we would need five more Earths just to sustain the current population. In Sweden the average citizen has a footprint of about twelve acres, while Mexico is setting examples at two and a half acres per person.

I took the quiz and found out that, even though I am a vegetarian and have a relatively ecofriendly lifestyle, I still require eight acres’ worth of natural resources to support myself. If everyone lived like me, we would still need twice as much Earth than exists to sustain the current population. If I cut out dairy products, my ecological footprint drops by two acres, and if I stop using airplanes I’m down to just four acres total, which is, theoretically, a sustainable lifestyle for this planet. These changes are possible for me, and necessary if I want to walk my talk. And you?

Eat Good Food

If you change only one thing about your lifestyle, this should be it. An organic diet of fresh, local foods leads to a sound mind, a sound body, and a sound ecology. In a way, organic food is a gateway drug to an ecological consciousness. When you eat organically, your body chemistry changes and you become more attuned to the subtle harmonies of nature.

I know I sound a little far out here, but millions of people are victims of the self-imposed physical and emotional malnutrition that results from a lifetime of gastronomic complacency—and look at the sick, unsustainable culture they live in. I am here to tell you: The food is the key. This is biologically, spiritually, socially, and simply, true.

Many common diseases can be largely avoided through dietary means, including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and of course emphysema, alcoholism, and obesity. Other afflictions, such as asthma, fatigue, chronic pain, and most skin problems, can be traced back to food allergies, most commonly to industrial foods such as wheat, soy, and meat.

An ecological lifestyle depends upon responsible and ethical food choices. It is extremely difficult to become a creative, self-actualized individual in a healthy, ecological culture when all you’ve had to eat is Twinkies and Taco Bell. Arguably much of the violence and stupidity in the world today could be avoided if people were better nourished and thus better able to make rational choices. When was the last time you behaved poorly because you were not feeding yourself properly?

One of the biggest barriers to eating a 100 percent local and organic diet is availability. Especially in urban areas, even if you grow a big garden at home, you will probably have to supplement your diet with food from off site, but shrink wrapped organic mangoes from five thousand miles away are not the solution. Look for supplies as close to home as possible, and try to avoid trucked in and/or packaged goods.

The average piece of produce consumed in the United States travels around fifteen hundred miles from farm to table, almost as far as Sacagawea traveled with Lewis and Clark, and three times farther than a healthy American walks in a whole year. Consider the embedded energies in everything you consume and make choices accordingly.

Consuming local, unpackaged, organically grown food reduces pollution and builds stronger communities. Especially in the United States, where the prevalence of consumerism has pulled us out of our gardens and into the mall, it is essential that we seek out and support producers and distributors of healthy, live food. This way we nurture local food security and ourselves at once. If you must import goods from afar, however, order in bulk from a local natural food store or online. If you don’t have a good local distributor, consider starting an organic food cooperative in your town or neighborhood.

When making consumer choices, beware of toxics wrapped in a green shroud—many companies label products as natural and even organic when the ingredients are barely edible, let alone good for you. Educate yourself about where your food comes from and make wise choices.

You might notice that I am avoiding a debate about animal products. This is such a multilayered issue that I will say only that whether you choose to be omnivorous, vegetarian, vegan, or opportunivore, let those choices come from a deep commitment to living in peaceful harmony with all species.

If you can’t find any organic farms or food sources locally, ask your current grocer to start stocking organic foods. Look online for organic garden clubs, food buyers’ co-ops, and regional farm associations. You might find a whole new community of people to share your time and interests with!

Going organic isn’t just about organic food or organic gardening: It’s a way of life. It’s not about certification or shopping at the most politically correct supermarket. Going organic is about taking control of your food supply and, thus, your life.

Share the Wealth

I cannot overstate the importance of sharing food, seeds, information, and other surpluses with your immediate community. Sharing reduces waste, encourages participation, and strengthens connections among people. As we recycle resources, promote biodiversity, and encourage relationships, we not only improve our own lives but also increase the integrity and liveability of the whole community.

Because it is impossible to create a self-reliant human settlement on one urban lot, these interactions are essential. We cannot conserve diversity, regenerate the natural world, and save the human race all by ourselves. We must work together in well organized yet autonomous networks to develop alternatives and bring about long term, localized change.

When I worked for Greenpeace I spent four nights a week for three years walking through all sorts of neighborhoods, knocking on doors and introducing myself to people. I found common ground with many people, and we talked about a wide range of issues, from toxics and pollution to cancer, education, and child care. Year after year I returned to the same houses, and people again welcomed me inside, gave me tea and cookies, and shared their latest concerns and successes.

An interesting thing about this work was the fact that many of the people whom I spoke with shared the interests and concerns of their neighbors, yet they did not know one another. For example, three houses on the same street all had organic vegetable gardens, yet the people had never met. Another house had a pile of unwanted wood out back while the neighbors bought firewood from the store.

Everywhere I went people who lived on the same city block had much in common yet were totally unaware of the close proximity of their like minded neighbors. If just one person had initiated a project or event in such a neighborhood, these people would have been able to connect, share resources, and organize toward a better community together.

Sharing improves our collective situation in several ways. First, we meet new people and learn about their interests. Through these connections, we make new friends, find new jobs, share new experiences, and discover new opportunities.

Next, we gain better access to food, land, education, health care, child care, and professional services. In the event of natural or political disaster, local support networks will be better equipped to survive than most isolated individuals could ever hope to be.

Third, we improve the environmental health of our bioregions when communities work together to provide food, shelter, and other resources to one another, and when they form coalitions to conserve water, restore wilderness, and steward organic farmland.

Sharing, the act of giving away what we have, challenges social and economic barriers by giving underprivileged people better access to resources and information. This helps establish a truer equality among community members and creates a healthy climate for a mutual and ecological evolution.

We are already a part of the ecological community that biologically supports us, and becoming intentional participants in the human community within that ecology opens up unlimited possibilities for peace and abundance.

In short, sharing helps give our lives more meaning and helps others find meaning through us.

By letting go of our individualistic aspirations and embracing the needs of the whole, we and our communities become simultaneously stronger, more essential, and more successful. We’ll jump deeper into strategies for building community in the next chapter. But first, let’s try on some personal choices that can set an example for our communities while enriching our own lives now.

Pedal Power

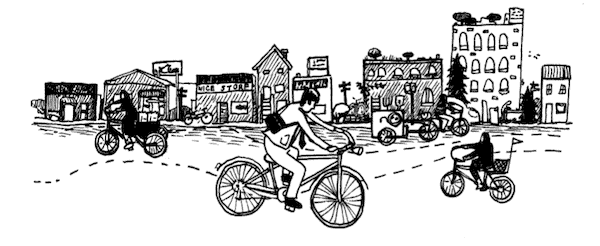

How we get around has a tremendous effect on the environment, our personal health, and how we treat other cultures. Automobile accidents are one of the leading causes of death, and road building destroys native ecosystems around the world daily. Cars kill people, animals, and insects and perpetuate the illusion that we can sustain an isolated, temperature controlled, Mach-speed culture.

We know that cars are horrible, airplanes worse, and trains and buses still pretty bad for the environment. But everyone wants to get from point A to point B sometimes, and we owe it to ourselves and our planet to use the most appropriate, energy efficient means possible, even if it means we have to give up a little privacy or convenience to do it.

The first and most obvious solution is to ditch that stinky old car and get on your bike. I grew up in the suburbs of Los Angeles, and while I spent plenty of time on a bike as a teenager, when I got my driver’s license at sixteen it was all over. I didn’t get on a bike again for almost ten years. When I finally did, I fell totally in love. Cars are prisons. Bikes are freedom. Why sit in traffic when you could be cruising happily along the river, singing with the birds and getting in shape?

In many places bikes are most people’s primary form of transportation. This is usually an economic choice, but you will find that people in these places are generally healthier, and that the air and water quality is much better in areas with fewer cars than in big, car-ridden

cities such as Los Angeles or New York. Still, even these metropolitan areas have well developed bike paths that lead all around the city. Maps are often available at local bike shops. Many city buses will allow you to bring a bike on board or have a rack mounted on the front of the bus for times when you need to get somewhere farther or faster.

How we get around has a tremendous effect on the environment, our personal health, and how we treat other cultures. Automobile accidents are one of the leading causes of death, and road building destroys native ecosystems around the world daily. Cars kill people, animals, and insects and perpetuate the illusion that we can sustain an isolated, temperature controlled, Mach-speed culture.

We know that cars are horrible, airplanes worse, and trains and buses still pretty bad for the environment. But everyone wants to get from point A to point B sometimes, and we owe it to ourselves and our planet to use the most appropriate, energy efficient means possible, even if it means we have to give up a little privacy or convenience to do it.

The first and most obvious solution is to ditch that stinky old car and get on your bike. I grew up in the suburbs of Los Angeles, and while I spent plenty of time on a bike as a teenager, when I got my driver’s license at sixteen it was all over. I didn’t get on a bike again for almost ten years. When I finally did, I fell totally in love. Cars are prisons. Bikes are freedom. Why sit in traffic when you could be cruising happily along the river, singing with the birds and getting in shape?

In many places bikes are most people’s primary form of transportation. This is usually an economic choice, but you will find that people in these places are generally healthier, and that the air and water quality is much better in areas with fewer cars than in big, car-ridden cities such as Los Angeles or New York.

Still, even these metropolitan areas have well developed bike paths that lead all around the city. Maps are often available at local bike shops. Many city buses will allow you to bring a bike on board or have a rack mounted on the front of the bus for times when you need to get somewhere farther or faster.

Sure, you might get wet when it rains or be a little sore the first few weeks, but life is short—why not experience it firsthand rather than from inside a rolling metal box? I don’t know how to convince you that the joys of choosing a bike as your main means of transportation far outweigh the inconveniences. I can only say, get a decent bike that fits your body (very important), put on a helmet to protect your brilliant mind, and give it a chance. Once you spend a few weeks cruising around, getting used to the new experience and increased exercise, you will surely agree that riding a bike to work, school, and everywhere else is easy and empowering.

If riding a bike instead of driving just doesn’t work for you—for physical, climatic, or other reasons—then here are a few other suggestions that will help you reduce your impact:Ride the Bus. Public transportation, whether bus, train, or rickshaw, isn’t just for people who are too young, too old, or too poor to drive. It’s for everyone, and if you pay taxes then you’re paying for it anyway, so why not ride? Riding the bus gives you time to read and interact with a diverse cross section of your community. With just a little planning and commitment, you can probably replace most of your driving with public transportation.

Share a Car. In many countries private vehicles don’t go anywhere unless they are full of people pitching in for gas money. We can also make this choice because we care about the environment. In South and Central America drivers pull up to busy intersections and call out for people who need rides around town. In the States car sharing usually happens in organized collectives, where people share insurance costs and coordinate rides and driving privileges through a website or central bulletin board.Go Biodiesel or SVO. Biodiesel is diesel fuel made from vegetable sources, most often soybeans, and it will power most diesel engines without any mechanical alterations. While the viability of such a fuel is entirely dependent on the integrity of the agriculture that produces it, it is a decidedly more feasible and less polluting option than the continued dependence on rapidly dwindling fossil fuel supplies.

Another, even more innovative solution is the use of recycled vegetable oil, also known as SVO, to run a diesel engine. The SVO approach does require a significant mechanical adjustment to your diesel engine. Kits and information can be found online; also look in the resources section for some good places to start.(7) Still, SVO is not perfect. You have to consider the embedded energy in the car itself (metal, plastic, labor, textiles), as well as in the fryer grease. Then there are the emissions caused by the burning oil, which, though less than with petrochemicals, still pollute. There are also several other alternative fuels being developed and used around the world, but none of them could be considered ecologically sustainable. Most of these seem “better” in some way than petrofuels, but generally, with cars, airplanes, and other gas hogs, the bad outweighs the good when you consider the long term.

Here’s another option:

Stay Home. In his treatise on paradise gardening Joe Hollis expounds the virtues of staying home. He writes, “The solution is not gasohol but reducing the reason for traveling (usually the getting and spending of money). Why not spend less time going away to make money to buy food and more time growing it?”

Unplug Your Life

If you haven’t killed your television already, the time is now. You will never regret it. If you are used to spending a lot of time channel surfing, it might be hard to imagine what else to do, but once you get started you will never run out of ideas.

The amount of electricity you use is directly proportionate to the long term damage your lifestyle inflicts upon your ecology. If you want to live with nature, you have to go outside. Turn everything off, leave the stereo headphones behind, and cultivate an outdoor life, rich in experience rather than gadgetry. Go outside and garden. Go for a walk. Stretch. Sing. Play an instrument. Write poetry. Tell jokes. Talk to your neighbors. Daydream. Hang out with dogs and cats. Watch birds. Go swimming. Take a nap. Cook. Read. Play with children. Dance. Make love.

Once you’re free from the TV, take a look around at the rest of the machines in your life. Why not eliminate the microwave, the coffee maker, the leaf blower, the alarm clock, and the bug zapper, and open up all that space for creative projects? Wasteful energy sinks like these are unnecessary trinkets at best. Even mainstream essentials such as stoves, refrigerators, and water heaters can become more efficient or be eliminated altogether, depending on your diet, climate, and comfort level.

We’ll start with the small stuff. First, replace the microwave with better planning; fewer leftovers means less need for reheating. It doesn’t really take that much longer to cook food on a regular stove anyway. Next, drink organic tea from local herbs instead of coffee, or at least use a French press instead of an electric brewer. Leaf blowers and bug zappers are just absurd—lose them immediately if you are at all serious about ecological living. Other appliances? Dry clothes outside or over a woodstove. Wash dishes by hand. Shave with a straight razor. Most electric gadgets are just wasting precious energy as well as your time and your money.

The stove, fridge, and water heater are a little more difficult to let go of for some people. Let’s look at each of these briefly.

Energy-Efficient Cooking and Heating

There are several excellent ways to conserve energy while cooking food, heating water, and heating your house. You can use recycled materials to build solar ovens, solar water heaters, fuel efficient stoves, and heat exchangers, as well as to insulate existing stoves, water tanks, and buildings. I don’t have room in this book to go into much detail about these effective and highly valuable options, but I can provide a brief overview and direct you to the resources section for a list of excellent references.

We’ll start with cooking. Most people in the States use either an electric stove—the least efficient use of energy—or a gas stove, which is better, but still very consumptive and wasteful. But around the world the most common way to cook food is on a wood burning stove.

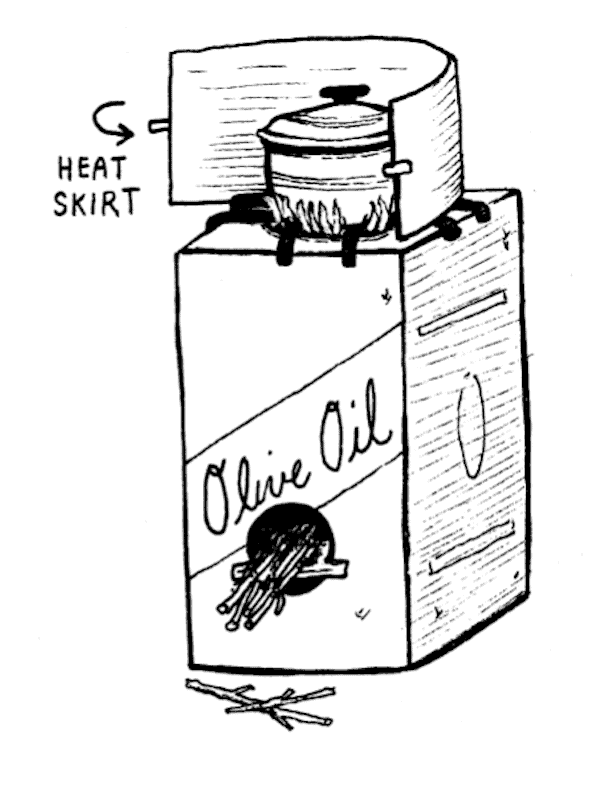

Aprovecho Research Center in Cottage Grove, Oregon, has a team of stove builders who travel around the world building fuel efficient wood burning stoves. Many of their designs are easy to construct with recycled resources and use less fuel and cause less pollution than any other type of cooking. They also offer some excellent designs for solar ovens that bake bread (and cookies!) using just the sun.

Whatever type of stove you use, you can save fuel by building a small shield that fits around the flame and your pot, keeping the heat focused on cooking your food rather than letting it dissipate outward. You can also use a blanket box (see the sidebar above), which uses insulation to finish cooking the food after you remove it from the stove.

When using a woodstove to heat a building, consider building a heat exchanger. This is a double walled metal cylinder that wraps around your stovepipe, much like the little cooking shield above wraps around a warm pot. The heat exchanger increases the surface area of the stovepipe and keeps significantly more of the heat from the stove in the room. Heat exchangers have been shown to cut fuel needs in half or better.

Cook with a Blanket Box

Cook without cooking, in a blanket box!

One way to reduce energy consumption in the kitchen is to use a blanket box for cooking. A blanket box insulates the pot so you can take it off the stove but keep cooking whatever is inside. The box should be big enough to hold a soup pan or stew pot. An insulated picnic cooler, found used at a thrift store, works very well, or just build a simple box out of recycled plywood scraps. Choose a pot with a tight fitting lid—I prefer stainless steel, with good handles. Now all you need is a small wool blanket.

The blanket box works great for steaming rice or vegetables, cooking beans or grains, and keeping food warm for hours. Just bring the food to a rolling boil on the stove, simmer for a few minutes, put on the lid, turn off the stove, and place the pot in the box. Wrap the blanket carefully around the pot, so you don’t upset the seal on the lid but do completely surround the pot with wool.

Now go do something else for a while and come back when you’re hungry! Blanket boxes work so well, and save so much energy, they should come standard in every house, right beside the stove.

Heating Water

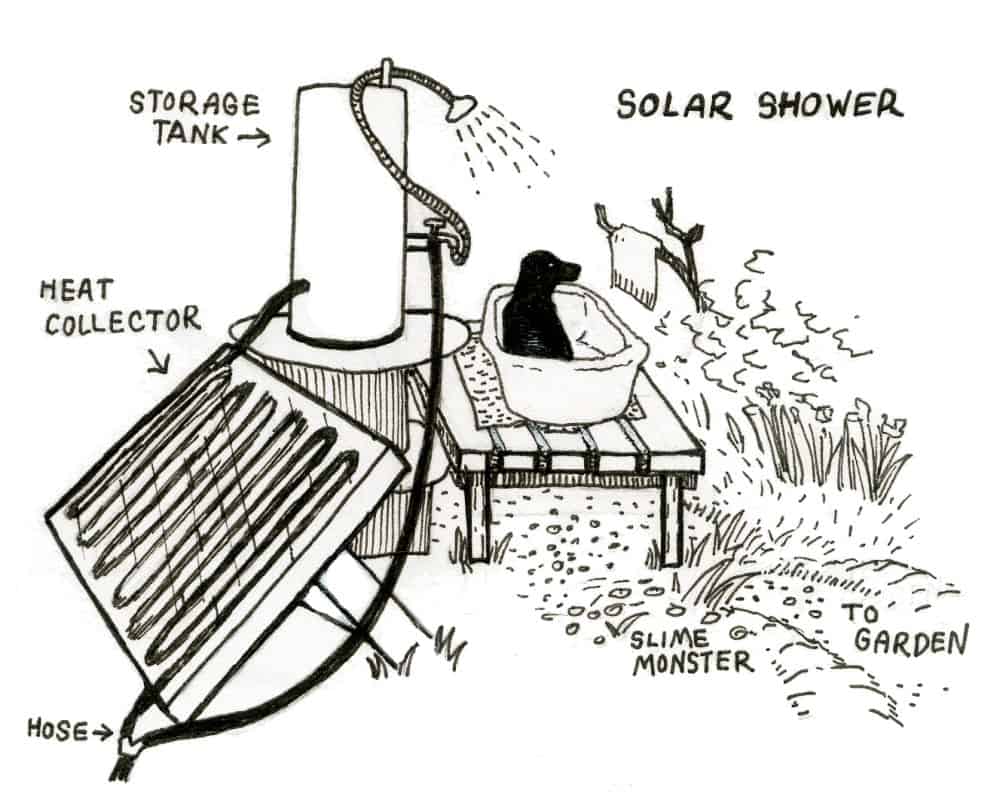

Similar technologies can be used to build an assortment of water heaters. Some of these use glass to magnify the sun’s rays and heat the water. Others involve running water pipes through or around stovepipes, using surplus heat from the stove. Some of these gadgets use gravity or convection to direct the water, while others require a pressurized water source. I have seen dozens of good examples of ecofriendly water heating, all of which could have been built by almost anyone in her own backyard. Again, I regret that there is no room here to discuss specific designs, but the resources section will point you in the right direction.

Eschew Freon

This includes the refrigerator and most air conditioners. You don’t have to give up on keeping you or your food cool; there are excellent alternatives, such as draft boxes, root cellars, solar fans, and design strategies.

The last refrigerator I lived with was like a fourth housemate in a small house with an adjacent living room/kitchen layout. We had no choice. We didn’t want the fridge in our faces all day, every day, so we set him up out in the carport and put a nice comfy chair in his place in the kitchen. We ran an extension cord out to him, but once he was out of sight, we found we never really wanted that ugly old fridge at our parties anyway. We kept our food in the cabinets, in bread boxes and jars, and started using the fridge only for luxury items like cheese and ice cream.

One day the neglected old fridge died. He took one final ticking-and- groaning heave and just shut down. We called the landlord and asked him to send a hearse. He asked if we wanted a replacement and we told him no thanks. That was four years ago, and though I have been known to stash a tub of ice cream in the neighbor’s fridge, I haven’t lived with one since.

Of all the consumer objects found in the average American home, the refrigerator is the most hideous, the most horrible. It’s huge. It hums all night. It leaks. It’s toxic, from start to finish. And it’s ugly. Even the most elegant designer refrigerator is a homely behemoth at best. Yet for many of us it hums happily through our relationship with food, every day, every hour of our lives. The fridge is where it all comes from and where it all goes to die. Later, we argue over who gets to scrape the green fur and pink goo out from under the drawers where we keep our “fresh” foods.

Refrigeration deteriorates nutritional value and kills the flavor in many fresh fruits and vegetables. You may have experienced a garden fresh tomato that tasted like hell after just a few hours in the fridge. Most of what people refrigerate will keep just fine on a shady shelf, unrefrigerated. Fresh eggs will keep for months; bread, fruits, and vegetables will last a week; most condiments have vinegar, which is an excellent natural preservative, and will keep for years.

Getting rid of your refrigerator is a great way to open up space in the kitchen, reduce unpleasant cleaning chores, and cut a big chunk out of your energy consumption at home. People lived without refrigerators for millennia, and billions still do. Mainstream society as a whole is extremely paranoid about bacteria, but as long as we wash our hands often and don’t eat anything that smells rotten, there isn’t much to fear. Buying local food helps; it’s fresher and will last much longer unrefrigerated.

Try building a draft box and/or a root cellar to store perishables. A draft box is a simple wooden cabinet with screened shelves, mounted onto a shady side of the house. One side opens into the kitchen, like any other cabinet. The back of the box is screened but open to the outside. The draft box uses convection to bring cool air up through the stored food.

There are also several types of root cellars, from a small pit with a picnic cooler in it to an actual structure built into the side of a hill. See the resources section for a list of excellent books on storing and preserving food. The point here is that your fridge is unnecessary and it might be time to let it go.

As for the air conditioners, try opening windows across the car or room from each other to get a cross ventilation going. Invest in a solar powered fan. Or try hanging damp cotton sheets in a breezy spot near the house and setting up an outdoor room there. They will create a cool microclimate that you can work, eat, or sleep in.

In short, as we lessen our dependence upon electricity, petrochemicals, and manufactured gadgets, we come closer to a more natural lifestyle. Plus we save money on electric bills and gadget purchase and repair costs.

Buy Less and Buy Local

So far we’ve looked at a wide array of consumer choices, from making dietary changes to using appropriate transportation and getting rid of unnecessary gadgets. When you simplify your life in these ways, you will quickly find that you need to go shopping much less, and that you need to buy less stuff to sustain your lifestyle. Still, until these ideas take deeper root in our culture, you will need to buy some things to support yourself and your family. Here are some pointers to help make those purchases as ecological as possible.

First, remember the design principle from the last chapter: “Replace consumption with creativity.” Every time you think you need to buy something, ask yourself how you can avoid buying it, what you can use instead, or whether you can innovate something out of recycled materials. A home full of handcrafted dishes and restored furniture is far more ecological—and in my opinion much more interesting—than a house full of prefab junk from Wal-Mart.

When you decide that you must have something, and that the only way to get it is by buying it, look for a source as close to you as possible. Choose a geographic area that makes sense for you, and buy only goods from that region. Some people buy only stuff made in America; others insist that everything they consume be produced within a five-hundred-mile radius of their home.

The closer you come to home, the less likely your purchases are to support the use of fossil fuels, excessive packaging and pollution, and questionable to horrid labor circumstances. Even Fair Trade goods are transported using diesel or jet fuel, and just because workers are being paid more than at other factories near them doesn’t mean they are making a living wage, or that they have access to any of the privileges the American distributors have. I suggest avoiding international goods whenever you can and looking for local alternatives to luxury items such as coffee, sugar, silk, petrochemicals, and—sadly—chocolate.

Beyond supporting local and organic economies, buying less and buying local means stepping away from the consumer culture and getting out from under the burden of so much stuff. Not only do you save money from buying less stuff (and selling what you have), but you also gain time by saving work hours to pay for stuff and spending less time moving all that stuff around (imagine never having to clean out the garage again). You create open space for new projects and change the aesthetics of your home by eliminating so much clutter and plastic.

Make Time

One of the most common excuses I hear for why people don’t garden and do the other things in this book is “I don’t have time.” Another is “I don’t have any money.” We’ve looked at many ways to be frugal with money by making good use of available resources, but what about time? I know of several excellent strategies for bringing more free time into a busy life, but before we get into the details, let’s make an important foray into the ways we as a culture perceive and document time.

The ancient Mayan calendar followed the cycles of Venus, the first and brightest star in the sky. Our modern clock and calendar system is based on the movements of Earth and her moon. However, these heavenly bodies never return to the exact same place twice. They rotate, they orbit, they speed up and slow down, but they do not do these things the same way every time. Because of this, the tools we use to document the passage of time must fudge the truth into predictable, repeating cycles, which are programmed into machines and printed out years ahead.

Billions of people organize their lives around this little ruse, convinced that the passage of time is a straight line from birth to death. Any little quiver, any bump on this long and narrow road, is seen as a perversion, an unlikely superstition best reserved for mad scientists and acidheads. But nothing in nature moves in a straight line, and time is no exception.

Time is not linear; it’s a cycle. It curls, spills, flows around obstacles, pools, flashes with light and darkness. It can be swallowed, absorbed, filtered, lost, and found. Time is not static; like every other element in a design, its form and value are relative to scale and placement within the system. A weekend for us is a lifetime to a butterfly. She will emerge, learn to survive, explore, and procreate, and then grow old and find a place to die, all in the time it takes us to mow the lawn, watch a few football games, and eat nine meals.

In reality, what we know about time is just a twinkle in the eye of the all-encompassing face of what we don’t understand, scientifically or otherwise. So why then do we need clocks, calendars, and computers to keep track of how long we’ve been alive, awake, asleep, at work, or on vacation? Some would say mainly for commerce. Businessmen in early urban cultures invented machines that would document time to assist them in collecting debts and managing investments.(8) Since then time has become synonymous with money, and around the world people sell their personal time to make money to survive.

Like money, time can be spent or saved, wasted and lost, and we never seem to have enough of it. But this commodified attitude about time does not take into account the many layers of experience that each moment contains. Unlike money, time is something of nature, something that exists all around us, whether we see it as valid or not. Money is about stuff, power, ownership; time is about life, experience, and freedom. To break out of this bewitching but utterly false marriage between money and time, we must return to the understanding of time as a pattern in living nature and find ways to integrate that pattern into our gardens and other projects.

Our perception of time has a great influence over the way we live. Just as the past and future exist in our minds, memories, records, and designs, so does the present exist in many layers at once. Like a paradise garden, our experience grows in exponential directions at once. Consider a time when you were traveling and every day became a significant and memorable series of events. Or a moment when you were passionately in love, or deeply involved in a project, and the whole day went by in what seemed like two hours. Was it like dreamtime, where lifetimes can go by in the twitch of an eye? How are these experiences of time different from when you are driving to work, watching television, or shopping?

Woody Guthrie said, “You can’t kill time without injuring eternity.”

So how can we make best use of the now while planning for the future, learning from the past, and being completely present? Here are some ideas.

Get Rid of Clocks, Calendars, and Mirrors

Try spending a week without any clocks, calendars, or mirrors. More consumer gadgets, these objects document and reflect the passage of time and keep us pretending that everything is linear, predictable, and altogether unnatural. Not to say you should never use one again, but consider letting go of your dependence on manufactured timekeeping objects. You will be amazed at the results. I could write a whole book on just this concept. Imagine waking up when you feel rested, eating when you are hungry, celebrating holidays on whatever day you want, and basing your self-image on how you feel rather than how you look.

I haven’t used an alarm clock for ten years, because I just can’t take the intrusion. Waking up like that can’t be good for mental health. I am a true believer in every person’s right to sleep as much as she needs to, but even when you have to get up early there are other ways to rouse yourself. Many people claim to have an excellent internal clock, and they tell stories of waking up right before the alarm goes off. You can probably do this too. If you tend to sleep very heavily and feel dependent on an alarm clock, try taking afternoon naps, cutting back on caffeine and sugar, and scheduling appointments for later in the day.

By removing the clock we place trust in ourselves to know when it is the right time to do something, such as wake up, eat, go to work, go to bed, and so forth. This might seem impractical for some people, but just try it for a few weeks. If you enjoy being free of the alarm but need to get up early every single morning, get a rooster or move your bed so that the morning sun shines on your face through the window. Or ask a neighbor who is a naturally early riser to wake you up for morning yoga, and you’ll stack function, friendship, and exercise.

Get Organized

Go through your house, garden, workplace, and anywhere else you spend time and organize it. Get rid of useless junk. Label drawers and cupboards if you need to. Make sure that everything is organized in such a way that you waste no time finding what you need.If you spend five minutes every day looking for your keys, that’s thirty hours each year. If you spend a few minutes creating a convenient place to keep your keys and train yourself to put them there, you can use the saved time for something you enjoy. Similarly, if you spend an extra two minutes every time you walk out of the way to a toolshed, and you go there four times a week, you can save yourself seven hours a year by moving the toolshed closer to the path. Use this principle of relative location to establish easy, efficient patterns of use, and you will open up blocks of time in your life.

Stack Functions

Another way to bend time is to stack functions, or multitask, all day, every day. In this way we can get large amounts of work done with minimal time and effort. At home I am never empty-handed. I am always getting something, putting something away, moving something to a more relative location. If I am walking from one end of the house or the other, I always try to bring something with me that needs to go where I am going. It is possible, however, to overdo it, so be sure to give your mind and body a break whenever it seems appropriate. Don’t be a workaholic, and remember to look before you leap.

This brings us to the next point.

Think Things Through

A stitch in time saves nine, right? Just because you are making best use of your time doesn’t mean you need to be in a hurry. Haste makes waste, for real. Keep your wits about you, and take a minute to evaluate the effectiveness of each action. This sort of temperance could save years of time spent correcting mistakes. Use your observation skills to identify good opportunities, and make prudent choices that reflect your ecological ethic.

Quit Your Job

Now you think I’m crazy for sure, but you can certainly live on much less money, work less at unwanted jobs, and actually live a higher- quality life because of the freedom and creativity that comes with simplifying your life. It may be hard to imagine being able to pay the bills, but you’ll be surprised at how much money you save when you stop buying things new, limit purchases to those items you absolutely need, use alternative transportation, and cut back on the less essential things like cable TV and junk food. You can probably live a healthy, natural life on half as much money as you currently spend, and be at least as content as you are now, but doing less harm to the earth.

If you aren’t ready for an early retirement, consider evaluating the ecological integrity of your livelihood. Does the job you do cause more harm to the environment than you can correct by your own efforts? If so, how do you feel about it? Can you find a way to make ends meet that is more true to your ethics? This issue of “right livelihood” can be a sensitive one, but as we work to better our gardens and communities we must ask ourselves whether our worktime is as well spent as the boss might have us believe.

Take a moment to ask yourself—even write it down–What would I do with my time if I could retire today and not have to worry about money? Be realistic: Not everyone can live like a millionaire, and in fact no one should if we are to create an ecological, sane, healthy culture.

Again, once you make some changes in your lifestyle you may not need that job as much as you once did. Many jobs are just self- perpetuating time sinks; we have to dress nicely for work so we pay for expensive, uncomfortable clothes; we have to drive there so we buy cars and gas; we spend more money at the bar after work, and on therapy, shopping sprees, and expensive vacations, just to recover from the drudgery of it all. Then we spend more money trying to prove to ourselves that we don’t spend all our money making money: We buy Jet Skis, dune buggies, computer games, DVD players. Yet these are the products of a consumer society desperate for some tangible validation of its success, and quite obviously part of the problem, not the solution. Not only do these “toys” damage the environment from start to finish, they also rob us of our last hours of free time.

When expounding the virtues of ecological living, I am not just talking about the small but significant patches of forest saved by using recycled paper, or the fraction of a reduction in the local landfill because you sent less trash there. The best things about ecological living are the indirect effects in ourselves as we become more ecological individuals, and how that transformation manifests itself through every aspect of our lives.

Notes for Chapter 8

1. Ernest Callenbach, Living Poor with Style (San Francisco: Bantam, 1972), 4.

2. Mahatma K. Gandhi, as quoted in Voluntary Simplicity, the book that accompanies a discussion course by the same name, given by the Northwest Earth Institute (Portland, OR: Northwest Earth Institute, 1998).

3. Joe Hollis, “Paradise Gardening,” in Peter Lamborn Wilson and Bill Weinberg, Avant Gardening: Ecological Struggle in the City & the World (Seattle, WA: Autonomedia, 1999), 159.

4. To take the Ecological Footprint Quiz, visit www.earthday.net/footprint/info.asp.

5. Bring Recycling, “Recycling Reaps Rich Rewards,” www.bringrecycling.org/newsletters/03fallnews.html, 3 December 2005.

6. Used News, newsletter of Bring Recycling (Eugene, OR: Bring Recycling, 2003).

7. See examples of SVO conversion kits at www.greaseworks.org.

8. John Briggs and F. David Peat, The Seven Life Lessons of Chaos: Spiritual Wisdom from the Science of Change (New York: HarperPerennial, 2000).